︎Dances for the Future: The Radical Visions of the 19th-Century Dancer Loïe Fuller︎ Lauren LeBlanc︎Dances for the Future: The Radical Visions of the 19th-Century Dancer Loïe Fuller︎Lauren LeBlanc︎Dances for the Future: The Radical Visions of the 19th-Century Dancer Loïe Fuller︎Lauren LeBlanc

Library of Congress / Barbican

Dances for the Future:

The Radical Visions of the 19th-Century Dancer Loïe Fuller

Lauren LeBlanc

Growing up in post-Civil War America, Fuller came of age in a fractured world, unsure how to move forward as a united country. It was a muddled time for American culture as well as society. First as a child actress, then a dancer in burlesque, vaudeville and circus shows, her sole constant was her role as a consummate performer. Ultimately she embraced the free dance movement which was a reaction to the formalism of classical ballet. With flowing, silk costumes that masked her body, Fuller played with fluid movement and improvisation. This experimentation offered the opportunity to manipulate light and color, drawing the elements in as components of the dance.

︎Fuller has seen a revival by contemporary artists who empathize with her struggles to be taken seriously. Not just as artists or innovators or scientists, but as women.

The populist spirit that urged her to chase these different avenues became a double-edged sword. While her agility allowed her to bounce from one discipline to another, who would take her seriously? Working as both an actress and dancer prevented Fuller from fully establishing herself as a serious dancer with original work. Faced with these obstacles, she first performed her breakthrough “Serpentine Dance” between acts of a comedy. Never turn up your nose at an opportunity. That perseverance paid off but also brought on a slew of imitators. Finding greater freedom and validation abroad, Fuller moved to Paris in 1892. She would live there for the rest of her life, championed by the Art Nouveau and Symbolism movements. Her champions and colleagues were a storied community of renowned artists and scientists—Marie Curie, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Auguste Rodin, Maurice Denis, Stéphane Mallarmé.

Beyond merely using dance as a means to tell a story, Loïe Fuller expanded the expression of emotion through non-traditional means of communication. Rather than resign herself to traditional storytelling, Fuller mined nascent technologies of electricity and photography to break through artistic boundaries. Through her collaboration with scientists, she explored a more expansive interpretation of light and color. For Fuller, a lack of background or training was no barrier to her curiosity. While she may have harbored insecurity in other facets of her life, regarding her passions, she had no fear of pushing herself to learn more. It was through her fluid costumes and embrace of light and darkness that she elevated art to a new level of expression. This would have never been possible without her fearless embrace of innovation and the respect of a wide net of different communities.

Despite that broad support across many disciplines, Fuller has been eclipsed in fame by her contemporary, Isadora Duncan. Celebrated for their innovation, innovators suffer at the hands of what makes them so productive. When one is not easily contained, it is easy to reduce their gifts to that of the absurd. Their multifaceted lives make it hard to neatly define their role within culture. And while her art could be as wildly expressive as she may like it to be, there are limits to what audiences are willing to accept from their artists. With a longtime female lover, Fuller did not fall into a conventional narrative.

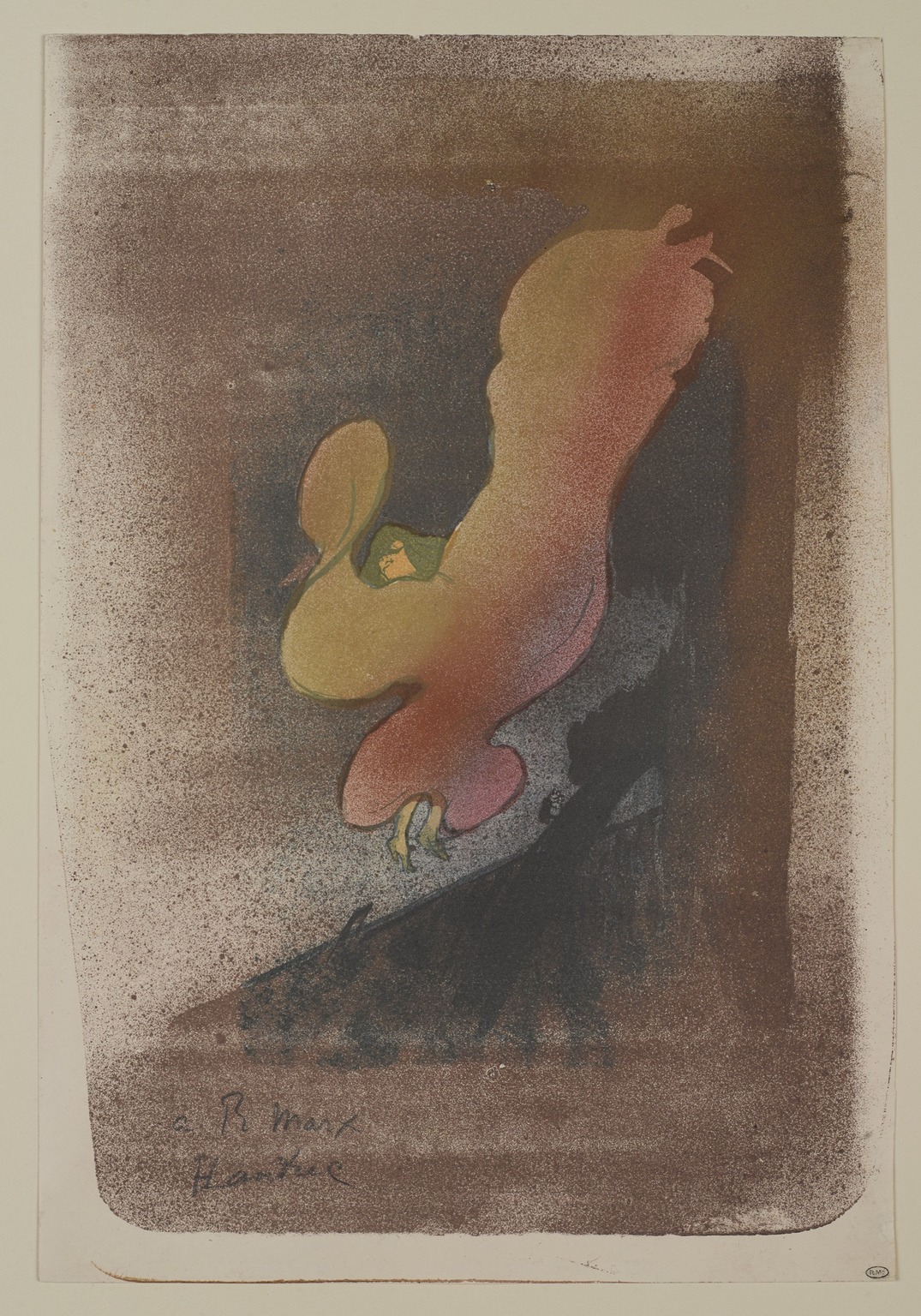

Miss Loïe Fuller, 1893. Color lithograph on wove paper, Sheet: 15 × 10 1/4 in. (38.1 × 26 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Museum Collection Fund.

So was she an artist? A would-be scientist? A bohemian diva? These questions remained unanswered for the remainder of the twentieth century. She quietly passed into legend. Yet why is she relevant today? Fuller has seen a revival by contemporary artists who empathize with her struggles to be taken seriously. Not just as artists or innovators or scientists, but as women. Her significance is impossible to ignore once you take a hard look at contemporary modern dance. The hypocrisy of her time is equally stark from this contemporary vantage point though that doesn’t stop critics and patrons from repeating the same mistakes.

While it’s too late for the artists themselves, efforts have been made to recover the contributions and outstanding achievements of remarkable figures lost to history. Fuller has received increased attention in recent years thanks to the 2016 film La Danseuse by Stéphanie di Giusto and also Taylor Swift, whose 2018 Reputation world tour included a performance inspired by the “Serpentine Dance.” The New York Times now runs a section called “Overlooked No More,” which offers obituaries of often marginalized people whose lives were not deemed worthy of an official Times obituary at the end of their lives. So often these individuals defy category. Recent columns have included Georgia Gilmore, whose group Club from Nowhere fed and funded the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and Ma Rainey, the Mother of the Blues.

Hilma af Klint, who was born the same year as Fuller and died in 1944, broke record attendance for the Guggenheim Museum with her 2018-2019 blockbuster exhibition “Paintings for the Future.” She had asked that her paintings remain out of the public eye for twenty years after her death, and must have recognized that a painter inspired by mystic religion as well as science and the natural world would not be given a fair assessment by mid-twentieth century critics. To recognize a capacity for beauty and yearn for a means to execute it shows great genius as well as bravery. It requires an artist who doesn’t simply dream with the materials at their disposal. It demands that you create new technology and materials and that when necessary, you dream up the ways that these visions can be made real. If af Klint’s reception is any indication, our cultural gatekeepers will continue to exhume the misfit innovators lost to history.