︎A Different Dimension︎Julie Curtiss in conversation with Dana Karwas︎A Different Dimension︎Julie Curtiss in conversation with Dana Karwas︎A Different Dimension︎Julie Curtiss in conversation with Dana Karwas

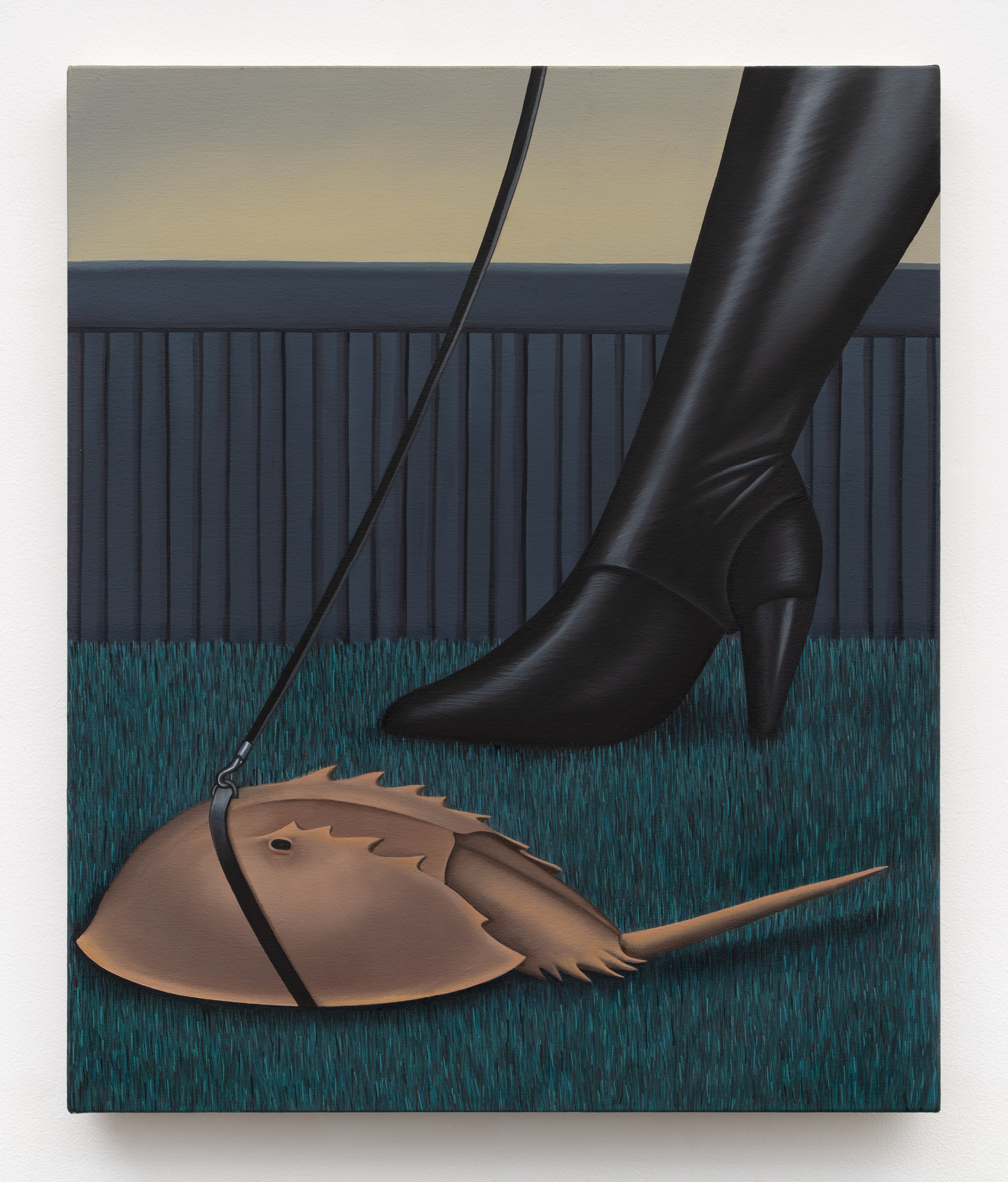

Julie Curtiss, Limule, 2021.

Acrylic and oil on canvas.

76.2 x 63.5 cm | 30 x 25 in.

© The artist. Photo © Charles Benton. Courtesy White Cube.

A Different Dimension

Julie Curtiss in conversation with Dana Karwas

The artist Julie Curtiss loves a mystery, a trick, a riddle. In the painting we chose for our Issue 4 cover, a squeaky clean horseshoe crab is being walked on a leash by a woman wearing a high-heeled, black leather boot. Enclosed in a privacy fence, the manicured lawn is a dark teal: Is it artificial grass? Beyond is a pale, featureless yellow sky, imbued with a smoky tinge. Is the world on fire? Are we glimpsing a near-apocalyptic future, in which relational dynamics, power structures, and social norms have undergone a total reordering? Horseshoe crabs have a rare blue blood that is crucial to medical research, and yet they are an endangered species. Are they the new status symbol? What are the new rules of the game?

Her images have a darkness, but Curtiss’ tone is always high-spirited. While her forms, angles, colors, and shapes are lushly defined, there is a clear signal of experimentation and fluidity—the “what if?” of vivid dreams, Jungian analysis, and emotional projection. Time and logic both stretch and bend, while meaning and sensuality meet jagged edges. She is often referred to as a Neo-Surrealist, but her landscapes feel like science fiction. It was no surprise to learn that during the pandemic, she revisited the classics: “Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and the Robot series by Isaac Asimov,” she says. “I like the mix of the past, present, and future altogether.”

Curtiss is a leading presence in contemporary art. Born in 1982 to a French mother and Vietnamese father, she studied at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is represented by White Cube. Dana Karwas spoke to her ahead of her first solo exhibition at Gagosian in Paris, “Suburban Lawns,” which opened in April 2025. A second solo show, “Maid in Feathers,” opened a few months later at White Cube Seoul.

—Alex Zafiris

Dana Karwas: When I first saw this painting, it reminded me of the French flâneur, or in this case, flâneuse.

Julie Curtiss: Absolutely!

DK: Why a horseshoe crab?

JC: I first saw one when I was quite young. I was in the sea with my friend. I thought it was a salad bowl, floating on the water. I turned it over. All these legs started to wriggle! I got so scared, I jumped into my friend’s arms and we swam away. We told our adventures to our parents. We just didn’t know what we were looking at.

Years later, I saw one in the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and I realized it was what I’d seen in the sea. Fast forward: I’ve moved to New York, and I visit Fire Island. During mating season, a lot of them die on the beach. I grabbed one of the shells. It was lying around in my studio for a while. One day I was asked to contribute work to Two x Two, a fundraising initiative that benefits amfAR and the Dallas Museum of Art. They were having a Surrealist show. I was wondering what I could paint—sometimes ideas come when I let my brain wander. My eyes stopped on the shell. I made several sketches. For me, the framing of the situation comes first, then things slowly come together. Usually I end up zooming in. That’s why you just see a foot, and a piece of the leash.

My female characters are extensions of me.︎My female characters are extensions of me.︎

At first, I thought: “I’m going to make this a high heel.” Then: “No, it has to be a boot, because she’s got to be armored, like the horseshoe crab.” My work is about culture and nature, but it’s also psychological. My female characters are extensions of me. All the other elements in the paintings are also extensions of her, and her projections.

Horseshoe crabs are prehistoric creatures that look like they come from a different dimension. It could represent the most alien part of life, or the most primitive part of that woman. Why is it on a leash? Maybe she’s very comfortable with her primitive side. Or maybe she tamed it. They are both armored, and together they take a stroll. It’s an intimate relationship.

DK: When you create, are you responding to the current climate or your internal world? Both?

JC: Definitely both. Projection is a way of internalizing external things, or external events. Finding objectivity and subjectivity. Sometimes they’re not at all autobiographical, but do reflect on certain states of mind or being. And my being is, of course, influenced by what’s happening in the world. During Covid, this theme of Chaos + Control was on my mind a lot. I was thinking on a much more political, sociological, and scientific level. I became much more aware of my references. But also, lately, it’s been more about having been pregnant, and very concerned about fertility—doing something that humans have been doing for centuries, doing as nature does. My husband and I bought a house in Florida. I’m surrounded by really wild nature.

DK: What is it about nature that attracts you?

JC: A very specific type of creature makes its way into my paintings. Ones that people would consider a little strange, or not necessarily something you would want to paint. Cockroaches, lobsters, Ibis birds—things that are slightly creepy. Rarely do I paint cute things. Sometimes a cat tail will make its way in, or a dog snout. I love nature and culture, but also attraction and repulsion. The familiar and alien. I like contrasts, those polar opposites. I choose these animals that provoke something in the subconscious. Snakes, fish. I don’t paint faces. The only eyes I paint are on the creatures.

I don’t paint faces. The only eyes I paint are on the creatures.︎I don’t paint faces. The only eyes I paint are on the creatures.︎

DK: There’s a strong relationship to the female body in your work. How has that evolved?

JC: I’ve been painting and doing a lot of different things over a long period of time. My work started to really take off when I decided to reduce my language. I was like, “OK: What I’m doing is not working. Let me just go back to a few distinctive elements, and see how many combinations I can put them in, and how far I can stretch them.”

At the time, I was watching a lot of Hitchcock. I was fascinated by the female protagonists because they’re very archetypal, and clouded in mystery. They’re very removed, but you’re always so close to them. It’s a very remote idea of a woman. They’re very beautiful. The hair and makeup, the figure. A lot of that femininity comes through, but it’s like a costume. With this film noir influence, I would crop the bodies to focus on one body part. It was convenient, but also nice, because then you have to make up for the whole missing image. It leaves a lot to the imagination. I add a lot of flat shadows over the background—this refers to the theater. I see it as a mental, internal theater with shadow. I’m really Jungian, so I love the idea of the shadow of a woman too, which is another archetype. Over time, my female figures have become more complex and a little less stereotypical, which gives me room for a little more realism.

DK: How has being a mother influenced, or played into, your ideas?

JC: It is still new to me. The work I did just after giving birth was a series in black and white, focusing on those first days of haziness. It was a hard time for me. I went through a lot of physical depression and anxiety from a hormonal imbalance. I was really struggling for about four months. Then I got better: it balanced out, I figured it out. Depictions of motherhood are always pretty, sweet, and soft. My series has a softness to it, and also definitely a darkness, a high contrast. I’m going to try to build on that. My new work has to do with motherhood, but not in an obvious way: there are almost no babies in it. It’s motherhood as extension of the self, and general ideas of pregnancy. I gave birth just before a solar eclipse, so I include that. There was a sense of these two things coming together and then separating, which I think is symbolic. It is influencing the work quite a bit.

DK: It’s like a seismic shift happens. In the brain, too.

JC: Oh yeah. I mean, if you are not changed after birth, then there’s something wrong.

DK: I’d love to know more about what the theme Chaos + Control means to you.

Nature is chaotic—too much of it can mean death. But too much control can mean death as well.︎Nature is chaotic—too much of it can mean death. But too much control can mean death as well.︎

JC: Florida has become a source of inspiration. I’m not familiar with it yet—I’m French, so it is very exotic. I also kind of hate it, obviously, but it’s very rich for me visually. Florida is such a wild place. The creatures, the wilderness, the hurricanes. People want to control their environment. Our neighbors across the street replaced their entire natural lawn with Astroturf. Nature is chaotic—too much of it can mean death. But too much control can mean death as well, because I find the suburbs very boring. It makes me want to run away. It’s a balancing act between chaos and control. You can see this for instance in the painting Tropical Dawn. A living room has been taken over by a tropical forest. Everything is in high contrast.

DK: There is so much humor in your work. I love the painting Serpent (2023), with the huge snake swallowing a couple whole. All you can see is this huge mouth, and their entwined feet.

JC: I think it comes from how the contrasts of life are more surreal than fiction. The juxtaposition of things that don’t belong together. Or thinking that you saw something and actually, when you look closer, you realize it was just your imagination playing a trick on you. Like visual rhymes. The shellfish as an ice cream. It’s trickery, contrast, and contradiction, and somehow it coexists very well in the same image. Usually I start there.

DK: With the humor there is darkness too, and sexuality, for instance in Freudian Slip (2022). It’s a close-up of a young woman’s bare legs on a table. A wooden cane, held by an old man’s hand, is being inserted into her. It made me think about the exhilarating nature of birth—a lot of extremes happening in contrast. There’s a circle.

JC: Yeah, that one is dark. People are disturbed by it. It is a circle. It actually came from a dream. I woke up and was really perplexed, then I realized, “Oh, your mind presents you with riddles.” I liked the idea of the cane, an object that represented old age, and the cane impregnating a woman, to start the cycle of life. It’s a loop. At first I presented a whole Freudian figure with a beard with a woman in a gynecology setup on a table. But it was too much, too crude. Not mysterious enough. I took things away, and it became like I was introspectively prying inside this woman. It was a whole psychological thing. Showing less was doing more.