︎Threshold Spaces︎Balarama Heller︎Threshold Spaces︎Balarama Heller︎Threshold Spaces︎Balarama Heller

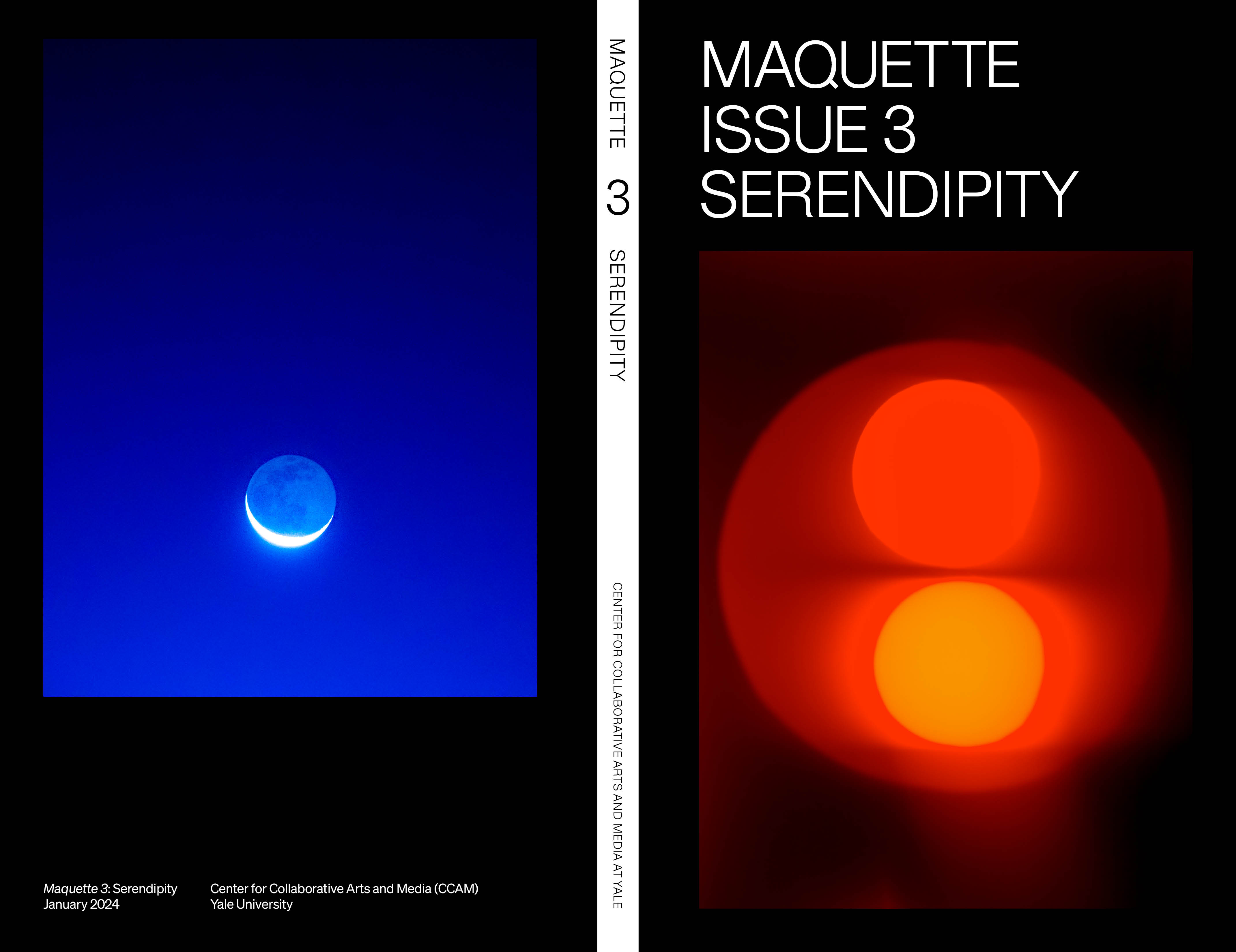

Maquette 3: Serendipity cover images by Balarama Heller.

Threshold Spaces

Balarama Heller

The only person I could think of who could front (and back) this issue of Maquette is the artist and photographer Balarama Heller. His work gives shape to those elusive feelings and patterns we think we understand, but in truth, know nothing about. His eye reminds us that we are of this Earth, but not in control of it—and nor should we be.

Based in New York City, Heller’s practice delves into the primal qualities of light, form, and color. His instinct for abstraction lends all of his imagery—from commissioned to personal—an aura of receptivity. “Part of my work is about pressing on the interconnectedness of us, and the relational aspect of everything: de-centering this idea that we are generating everything, and in a vacuum,” he says. “It’s about making yourself available to be in communication with these forces: reducing that sense of separation between ourselves and the outside.”

His most recent solo exhibition was Sacred Place with Aperture Foundation/Artsy. Recent group shows include The Bunker ArtSpace, Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody; Maelstrom at 303 Gallery; You Can’t Win: Jack Black’s America curated by Randy Kennedy at Fortnight Institute; What’s Outside the Window? at ReadingRoom, Melbourne; agnès b. in New York; New Artists at Red Hook Labs, and the 2015 Aperture Summer Open. In 2014, he published his first artist book, Into and Through. His series Zero at the Bone received First Place for the 2017 Center Awards Editor’s Choice and runner-up for the 2017 Aperture Portfolio Prize. His 2019 project Sacred Place was featured in Aperture Magazine issue 241, with a text by Pico Iyer. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and the British Review of Photography. He has photographed many artists, among them Mickalene Thomas, Hank Willis Thomas, Marilyn Minter, Arthur Jafa, Tehching Hsieh, and Alejandro Jodorowsky.

—Alex Zafiris

Alex Zafiris: I’m so glad to have these images on the print cover of Maquette, because for me, they encapsulate the mystery and feeling of what serendipity is. Many questions were raised in this issue, and most of them were left un-answered. What does serendipity mean for you?

Balarama Heller: On a rational level, I’m more in the determinism camp. Everything that is happening now is a result of what came before. There’s a tension around the idea that we have free will. Could things be different? There’s no real way to know—on an evidence-based level, we’re only aware of one outcome: this reality. Which itself is a result of everything going back to the beginning of time. All those billions of factors, interacting with each other, resulted in the now. On an intuitive level, I don’t want to believe that. Maybe it’s egotistical that I believe in free will, that I have volition. But when I really interrogate it, I’m not sure. I’m always being held in tension with these two ideas. Scientists suggest that, before you make a decision, there’s a pre-cognitive awareness that has already made the choice for you. When you take that into account, it opens up [Pandora’s] box. What is that pre-cognitive, master controller? This creates a really interesting atmosphere to pull apart our assumptions about fate and serendipity.

The grounded part of me wants to be more deterministic. But I also believe that determinism doesn’t absolve humans of moral responsibility. You have to act as though you have free will, even if we may not have it.

What I’m trying to do as an artist is move into unknown spaces, unknown territory; that’s what excites and drives me. When I start making something, I’m coming to the decision to create at the mercy of the multitude of factors of history that led to me being here. I begin with a pretty firm idea—I sketch it on paper, I write about it, I conceptualize it. I know that the result is going to be partly the hardened concept that I have, and the rest is happy accidents. I don’t have control over certain things—I leave room for that. If I attained the result that I envisioned every time, I would just be bored. The decision point—when you think, ‘Okay, this is it’—is when you have communicated with that image long enough and it still holds a sense of mystery and awe. That something came through a portal of the unknown, and the residue of that is sitting there in that image and holding space.

AZ: Tell me about these two photographs on the covers of Maquette.

BH: The cover image is from the project “Origins and Ends” which I began in 2020. It’s about looking at an imagined, before or after Planck time, the moment at the beginning of the universe, right after the Big Bang, when the raw formation of existence—both violent and beautiful—began to take shape, relationship and interaction began, on the most fundamental level. I say “imagined,” because at Planck time, the universe was completely opaque. If there were an observer, there would be no light to reveal what was happening. Light came 370,000 years later during an event known as the Great Recombination. Light is the symbolic, physical, and spiritual seed of significance that we might call consciousness. The fact that it functions as both a wave and particle—which is unique in the universe—holds special power, because it questions our conceptions and assumptions. The wave-particle duality. It is pure potential.

First Divide, Balarama Heller, 2020, from the series Origins and Ends.

This series is studio-based. I build sculptural pieces of paper by cutting shapes, up to four by six feet in size, lighting them in various ways, and then photographing them, sometimes using multiple exposures. I try to do the majority of this work all in-camera. I do some minimal intervention in post-production.

These are not based on scientific images that I’ve seen before. It’s my own personal imagined catalogue of universal archetypes, and envisioning what this would or will look like, or did look like or feel like—a beautiful space of expansion and contraction. I’m always trying to look into source or creation moments.

Light is the symbolic, physical, and spiritual seed of significance that we might call consciousness.︎Light is the symbolic, physical, and spiritual seed of significance that we might call consciousness.︎

I have also been trying to move away from more representational images. I’m dealing with primary shapes, colors, and forms, and how they interact on a symbolic level. We’re so trained to look at a photograph and see it as a document, and ask the who, what, where, when, how questions. We rarely ask that when looking at a painting, or an abstract image. I’m primarily interested in photography as a medium, because of its relationship to light, and light being this primordial force—the only way we are here, or know ourselves, or know our environment.

AZ: Have you seen William Klein’s light experiments?

BH: I love them. Also: the work that Berenice Abbott did at MIT. That has been really inspirational to me. Other artists working in camera-less photography whose process really excites me are Garry Fabian Miller, Eileen Quinlan, David Benjamin Sherry, Anne Hardy and Ellen Carey, to name a few. Adam Fuss developed a really incredible way of working without a camera. By all definitions, he’s creating photograms. But the way that he’s intervening with light and color to create these final images is so inspiring. There’s a group of photographers who are thematically working with the primary elements of nature, time, light, and color—most of them English—living in the countryside and intervening with the materials in that way. That’s the zone of photography I gravitate towards. An American photographer, on the west coast, is Chris McCaw. He built this giant, wagon-pulled view camera. He somehow got hold of a lens that was used on the U2 spy plane. He puts photo-positive paper in the back of it, and then does multi-hour exposures. He’s able to create that magnifying glass effect, where the light physically burns the paper, tracing the path of the Moon or the Sun. Then he develops it and you have this ghostly landscape, with this burn across the image, tracking time, physically imbuing the paper and rendering it into an object. It’s really wonderful.

Slow Fall, Balarama Heller, 2021, from the series Earth Mass.

The Moon image on the back cover of Maquette is from an ongoing series called “Earth Mass.” I want to address humanity’s primordial relationship with the Earth and the wider cosmos. The idea is to push back against the notion that we are somehow separate from nature. Humans insist on being distinct from nature to create order, but our collective actions have a disruptive effect on the systems of the planet. I suggest that a path out of this destruction is de-centering our species, viewing ourselves as intrinsic and indistinct from everything else that exists. This can do two things. It can underscore the idea that what we do to the environment, we do to ourselves; and it can soften the concept that humans have a destiny that is grander than other manifestations of life in the Universe. I saw Arthur Jafa’s AGHDRA piece this summer in Arles, and to me it perfectly communicates this. If and when we cease to be a species—the world will still exist. It is a timeless look into the primordial before or after. I don’t read it as a warning, or doom art. It is a perspective that could perhaps link us to a more connected present. “Earth Mass” is also a way of shaping the wider world as a temple for contemplation, a place of worship and prayer to existence itself. Animals, rocks, trees, the elements, celestial bodies like the Moon and stars are all active participants in this ritual of acknowledgment. I hope to break down the hierarchy of these participants and put them on equal footing. The images I am drawn to create are essentially symbols and archetypes that thread the major components of life together, all emerging from abyssal darkness.

AZ: How much do these images relate to your (sleeping) dream life?

BH: I love this question because in my early twenties, I got this Stanford manual on lucid dreaming from the 70s. I put it into practice, and within a month was able to start lucid dreaming on a fairly regular basis. It doesn’t happen predictably. It happened once or twice a week during the intense period that I was training. In the lucid state, everything in the dream world is animated. You can demand any object to communicate with you. Everything is imbued with significance. You could approach a toaster and say, “reveal your true form!” It’s a really interesting way to engage with your consciousness that doesn’t have the limitations of waking life. A recurring theme for me is that I would end up in these environments where I was having to go through thresholds, or gates. There were always these guardians who were allowing people to go through—you’d have to negotiate your fear with them. I would pass through to these spaces of primordial creation. This informed much of what I’m doing now, even though I don’t practice lucid dreaming anymore. But as an artist, I found it a direct and powerful tool to investigate yourself.

The images I am drawn to create are essentially symbols and archetypes that thread the major components of life together.︎The images I am drawn to create are essentially symbols and archetypes that thread the major components of life together.︎

I’m not proposing that I was literally entering another realm or a metaverse—although, who knows? But it was a genuinely important source of creativity and ideas. Years later, I read David Lynch’s philosophy on how to funnel down into your unconscious, and access this source of creativity using different meditation practices, where you enter a hypnogogic state, in between the sleeping and awaking state. This felt akin to that. Lynch talks about the universal consciousness, that all of these ideas are there for the taking. This puts a spotlight on the notion of whether we’re the originators of ideas, or accessing them from the subconscious or a universal conscious realm. I’ve also read about therapeutic or traditional uses of these threshold spaces that you can work through, to get to another zone of reality. To me, all of this links together as a way to examine the ideas in my work.

AZ: Are there any images and feelings from your childhood that inform your process?

BH: Absolutely. For a bit of background: I grew up in the Hari Krishna movement in the United States—that’s why I have a Sanskrit name, Balarama. As a child, we moved in and out of these ashram communities in different parts of the country. The times we were in the ashram were very intense. There’s so much visual inspiration in the Hindu canon of literature and mythology. It’s a literalist, fundamentalist religion. You’re taught that Vishnu is an avatar of Krishna and has four arms, whose skin is the color of a stormy rain cloud, bluish black—these are all things that you believe in and take literally. The first thing you do when you wake up at four a.m. is worship Tulsi, a plant, which was very dear to Krishna. The plant is considered a goddess. You treat it as you would the most elevated God in the universe—you care for it, you protect it. When you look at it, your perception is in full personification mode. I think that this early experience shaped my cosmological worldview and how I relate to ritual objects. Nature was really impactful. Even though I’m not religious at all anymore, a primary interest of mine is investigating the nature of spirituality and finding new vocabulary for it that is more my own. I’m still working with the themes that I grew up with, asking the ontological questions: Who are we? What are we here for? Where did we come from? Those grandiose questions are still a primary driver of what I’m doing in my artwork.