︎Memory Crystal︎Anežka Minaříková︎Memory Crystal︎Anežka Minaříková

My grandmother, Květoslava Mlčáková, loves to sing. My mother told me that when she was a child, my grandmother would dance around the living room with a portable magnetophone, microphone in her hand, singing from the top of her lungs. My mother and uncle thought it was annoying, since they had to participate in these frequent musical escapades. They still make fun of her for it.

I have a very different memory of my grandmother singing. Actually, she sang the first song that I remember. A nursery rhyme. It goes like this:

Kousavý pavouček vylezl na okap

Pak přišel déšt a pavoučka splách

Když vyšlo slunce a osušilo svět

Kousavý pavouček vyzezl zase zpět

Kousavý pavouček vylezl na okap

Pak přišel déšt a pavoučka splách

Když vyšlo slunce a osušilo svět

Kousavý pavouček vyzezl zase zpět

Pak přišel déšt a pavoučka splách

Když vyšlo slunce a osušilo svět

Kousavý pavouček vyzezl zase zpět

Kousavý pavouček vylezl na okap

Pak přišel déšt a pavoučka splách

Když vyšlo slunce a osušilo svět

Kousavý pavouček vyzezl zase zpět

It tells about a spider, the rain, and the sun. The spider is crawling up a gutter, but it starts raining, and he falls. Fortunately, the sun returns, and he soon climbs up again. The cycle continues. When my grandmother sang it to me, her fingers would crawl up my arm. I believed that there was a real spider, but I was not afraid. I forced her to sing it to me over and over again.

We have since travelled more than twenty-five times around the sun, and I have travelled thousands of miles away from my family. I miss them and think about them often. We speak only through mobile devices. I talk to my grandmother every day on Facebook Messenger. She sends me documentation of her day, her dog, and the titles of the shows she is watching. It made me think of our song, and later, as I lay in bed, I tried to look it up online. I always thought that it was a traditional Czech folk nursery song. But I found nothing.

I sent a message to my grandma: Where does your song come from?

She replied: It is from a movie with Meryl Streep that I watched a long time ago.

In the 1986 movie Heartburn, Streep sings Itsy Bitsy Spider to her child on a plane. It is a traditional Western folk nursery song. It turns out that my grandmother saw this film dubbed in Czech—and the song was translated, too. She liked it a lot, remembered it, adjusted some lyrics, then sang it to me.

I asked her to send me a message recording of a song through her phone. She made multiple attempts, laughing at first. Then all of a sudden, she was singing to me again. Listening to her, I was overwhelmed with emotions. I could feel her sitting next to me—her disembodied voice.

When I was studying graphic design at the Yale School of Art, I spoke with Paul Elliman, who is a Senior Critic there. A lot of his practice focuses on sound, technology, and language. I don’t know him very well, but I found myself telling him about my fear and guilt of not being in the Roudnice nad Labem with my grandmother as she gets older. It was an intimate topic to discuss with a stranger, but he said that he feels the same way about his family. He told me some fascinating stories of people’s various attempts to live forever by preserving the sound of a voice. He explained that a sound wave never disappears. That it travels through space for eternity. This is technically true, but it becomes indistinguishable with other atoms and particles and we cannot retrieve it or hear it as humans.

To be able to hear sounds of the past again, we need technology. This is not a new idea. Elliman told me that in 1860, the French printer and typesetter Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville recorded the folk song “Au Clair de la Lune" using his invention: The phonautograph. It created sketches of sounds waves on black paper. Almost a hundred and fifty years later, these phonautograms were converted into digital audio by scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California. Another more recent example is the The Golden Record that was sent out of our solar system abroad the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1977. This phonograph record was curated by a team led by Carl Sagan, intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial form who may find it, to learn about the diverse life on Earth. It includes a multitude of sample sounds from earth—including Kiss, Mother and Child, Wind, Rain, Surf, and Wild Dog—greetings in many languages, and also, 90 minutes of music, including Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.”

He explained that a sound wave never disappears. That it travels through space for eternity.︎

After talking to Elliman and learning all this, I decided to search for a contemporary medium that could carry my grandmother’s song forever across time and space.

Technology is a huge part of my life. I was fortunate enough to receive my first computer quite early, around nine or 10 years old. It was my favorite thing. I played games all the time; I loved the duality of it, building new worlds. It was very generative, and it helped me to learn English, especially playing Doom, Tomb Raider, and Sims.

I think it’s the reason I became a graphic designer. At first, I thought I would be a programmer, but then I took a class when I was 12 and realized that my brain is not wired to think in code. I was always thinking in shapes. It was really fun to make art with my computer. Designing feels similar—like I’m playing a simulation game—because of the software, and the way you control it, it almost feels like a game interface. You never know what you’ll end up with.

During my time at Yale, I was really trying to verbalize my interest in technology. I have this love for it that comes from my childhood; I use computers every day. That process, too, evolves and changes. Equally, doing the work about technology is something different. It’s a part of our life, and it just comes to me naturally. I think about: How does it work? Who does it work for? Does it work for us? Or does it work for somebody else? Stories about technology are everywhere; you can trace them back to conflict and war.

Designing feels similar—like I’m playing a simulation game—because of the software.︎

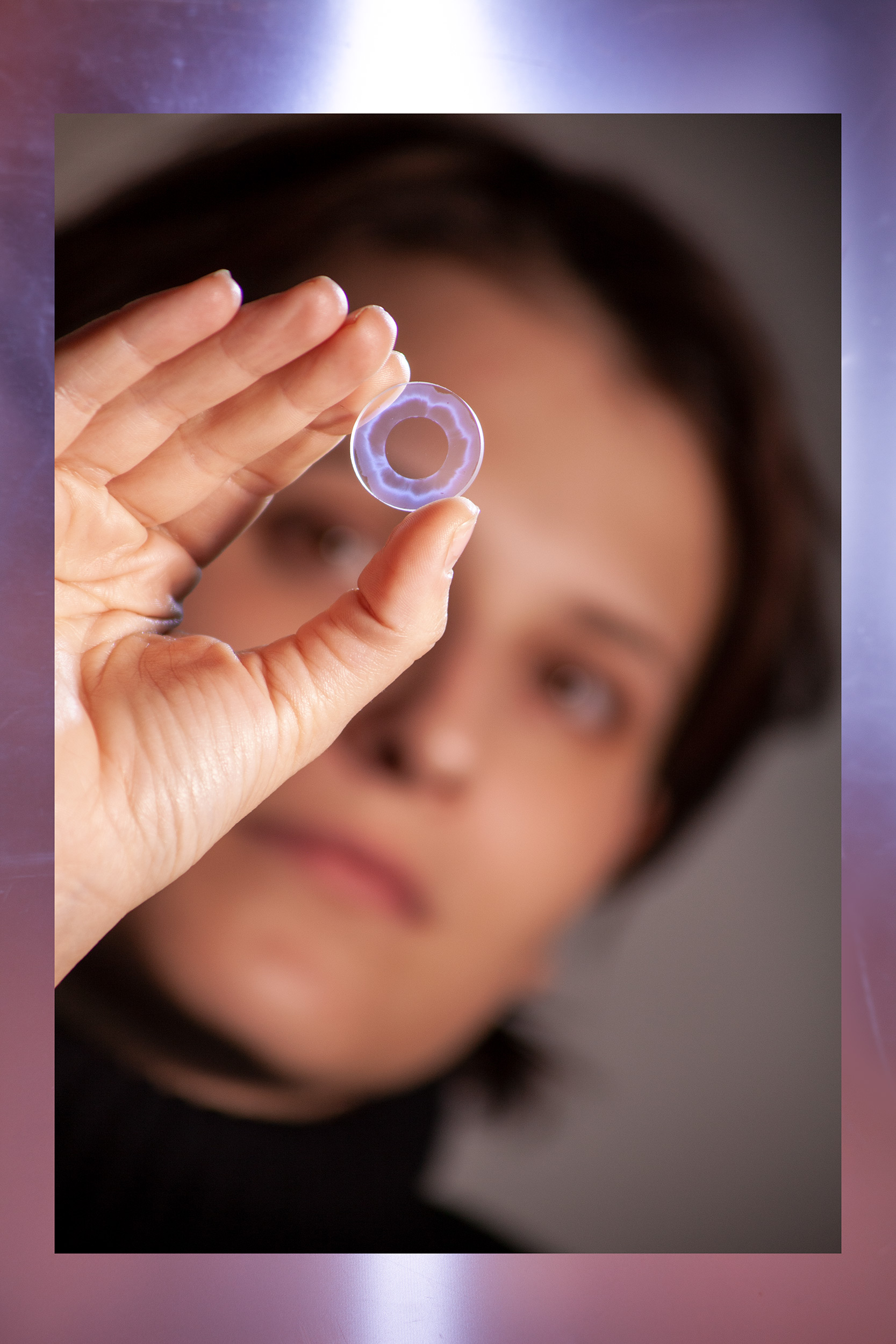

Elliman loves personal stories, and I was encouraged to continue this idea I had in my head. He understood my fear of my grandmother dying, and wanting to preserve her voice. My first thought about data storage was that they die too after some years, and they and their servers need to be constantly upgraded and saved again… but then through my research I read about the Superman Memory Crystal, a project run by Professor Peter Kazansky at the University of Southampton in the UK. The company is called Serendipity Photonics Group. Their work focuses on creating optical data storage that lasts for billions of years. They engrave it onto fused quartz or silica glass, which is a glass composed of almost pure silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) in an amorphous (non-crystalline) form. This ends up as small disks, and can hold 360 terabytes, and survive extreme temperatures. The team is right at the beginning of this experiment—they have lasered the Magna Carta, the Holy Bible, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. A few years ago, they collaborated with SpaceX, and gave Elon Musk a crystal that contained the three books of the Isaac Asimov Foundation Trilogy, which was launched into orbit in his Tesla.

I asked myself: Why not my grandmother’s song? Who really decides?

So I sent them a proposal with idea and the Facebook Messenger recording. I sent it to Professor Kazansky, and I didn’t hear anything for three months, but eventually he responded, saying that they would like to do it. Then the pandemic happened. Months later, I received an email telling me that they had recorded the song. Wow! Okay! They sent me some strange images of the data and some numbers, but I didn’t understand what it meant, and I asked them. Before I knew it, I was beamed by Skype into this conference room, totally unprepared. But they were so excited about it, saying that it was the first song they were able to engrave, that they usually engrave text and pictures, but songs are very hard. They explained that this was a milestone. My grandmother’s song!

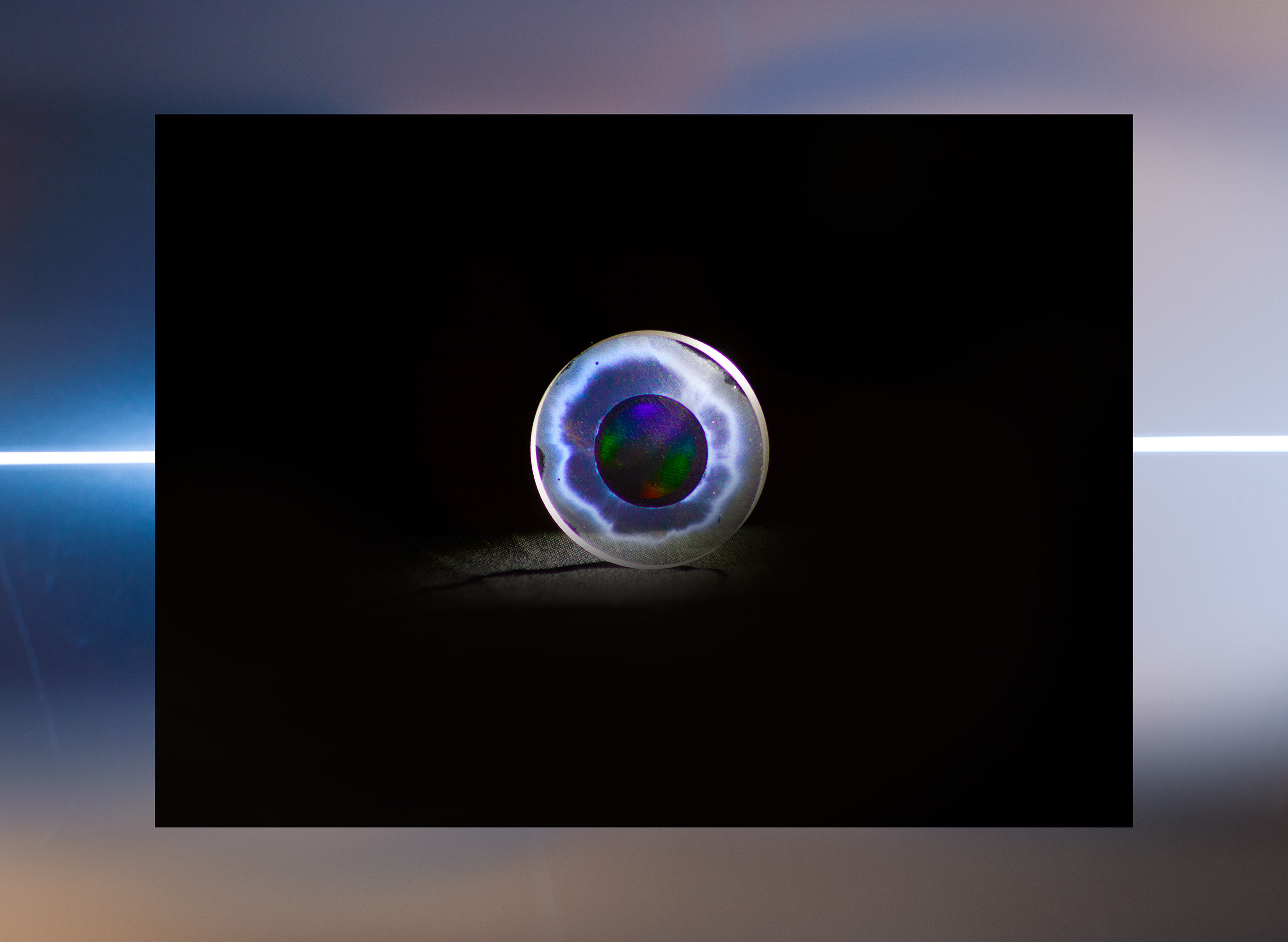

They explained the process: it takes 10 seconds to engrave with a very fast laser. To ensure that it is done properly, they need to read it manually with a microscope, which takes three days—like taking pictures of each part, and stitching them together. They sent me an image of a close-up of the crystal containing only six seconds of the song. It was taken by a microscope, and shows arrays of multi colored dots (voxel) of different sizes; these are read in order reconstruct the data. It is extraordinary, to see how this technology is so advanced, but so time-consuming.

They were just so excited, and I was elated.

Then, of course, I said, Can we talk about the design?

Nobody had mentioned it, except that they put instructions inside each disk, explaining how it should be read. I got really stuck for quite some time, thinking about it. At first, I thought I would keep the disk clean, without anything. Then I considered having the data on it, but it is already visible. I spoke to Elliman about it, and decided that I wanted to make it kind of open, and poetic—not like a scientific diagram, not calculated. In one of his emails, he attached an image of the sun’s corona, which according to the NASA website, is “the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere. The corona is usually hidden by the bright light of the Sun’s surface. That makes it difficult to see without using special instruments. However, the corona can be viewed during a total solar eclipse.” At first, I did not connect the dots. But when I looked at it again, I realized that I had seen it before. August 11, 1997: I was six years old. My younger sister was three, and we watched the total solar eclipse together with our grandparents. I remember we had a special instrument, a piece of glass of some type to prevent eye damage. I am not sure if we managed to observe it clearly because of the clouds, but I remember seeing images later that day on TV. Due to its trajectory, this was one of the most-viewed solar eclipses ever; because of that, I was able to find a clear photograph of it from that exact day with a visible corona surrounding the invisible sun. Total solar eclipses usually last about seven minutes or less, a short timespan to capture the moment before it is gone. Then it becomes a memory. I have not seen another eclipse since that summer day that I spent with my grandparents. I decided to send this image to the scientists to engrave it onto the memory crystal; it was created using the Schiller phenomenon, which is common in labradorite and moonstone. The effect makes the stone look like it has been lit from the inside.

Professor Kazansky is captivated with the idea of eternity. He is already thinking of the future of these crystals: digital gems, worn as jewelry. He really likes this notion of something being forever. I was lucky to meet this person. He is open-minded and interested in collaborating with artists. It really was a surprise; we really found each other.

It was created using the Schiller phenomenon, which is common in labradorite and moonstone.︎

When I finally received the crystal, it came in a plastic box. I was surprised by its size: very small and light, but feels solid, indestructible.

Photographer Monique Atherton describes her process for this story

You don’t take a photograph, you make it. —Ansel Adams

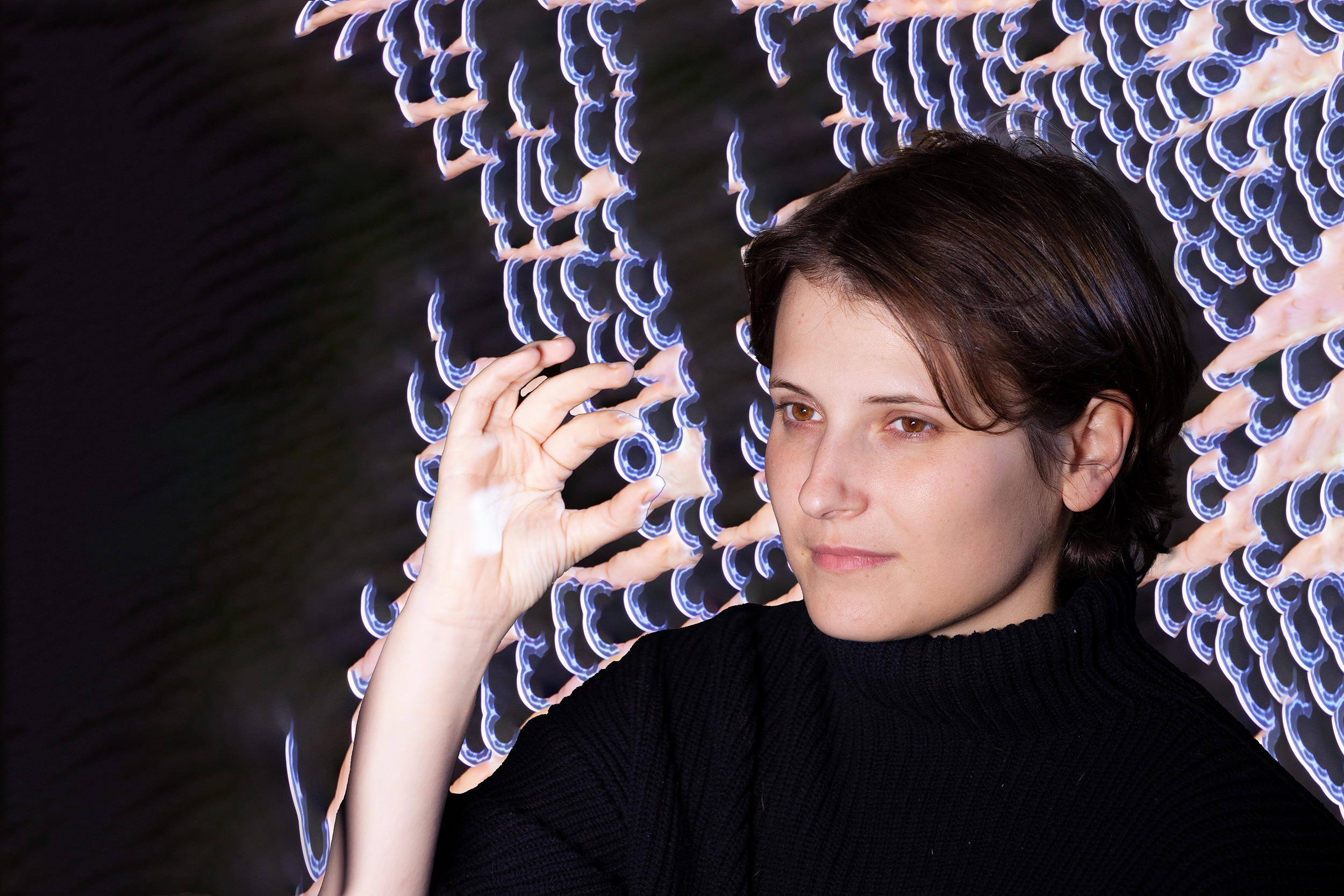

The immediacy of the photographic medium is deceptive. Even though the physical act of pressing down a shutter to capture an image generally takes a fraction of a second, there are many aspects of creating a photograph that are not visible to the viewer. The hours (and in some cases, years) of learning the technical settings of a camera and deciding what to use and when; the planning and setup; the focus and teamwork during a shoot; selecting an image to show; and the post-production of the final images tend to go unnoticed. The photographs for this article are no exception and it took five people and a total of about ten hours to make the images you see.

Photographing a crystal that changes with the light was fun and challenging. In addition to macro shots of the crystal, it was also important to photograph Anežka with the crystal given her personal connection to it. For the shoot which was held in my living room, I used my Canon 5D Mark II and a 300 millimeter zoom lens. This lens enabled me to get close ups of the crystal (which is only one inch in diameter) as well as shots of Anežka with the crystal. We used several backdrops including a light diffuser sheet from the inside of an LED television which also refracts light. For lighting, I used several different lights including LED panel lights, a ring light, several flashlights, cell phone flashlights and a high-powered bike light which we taped off to create a more direct light stream to “activate” the crystal—something that took a lot of coordination. Depending on which angle you viewed the crystal from you would see different aspects and details. Both of our partners were critical to helping us activate the crystal and they spent a significant amount of time holding flashlights in different angles while Anežka held or positioned the crystal and while I made the pictures.

I like options, so I shoot a lot of pictures then go back and pick out the best ones. For this shoot, I had about 550 selects to choose from. About a day after the shoot, I spent some time going through and selecting the top fifty images and then the next day, I made my selects and made some edits in Photoshop and shared them with Alex and Anežka for final selection.