︎Order Is Only Abstract︎Jess Nash︎Order Is Only Abstract︎Jess Nash︎Order Is Only Abstract︎Jess Nash

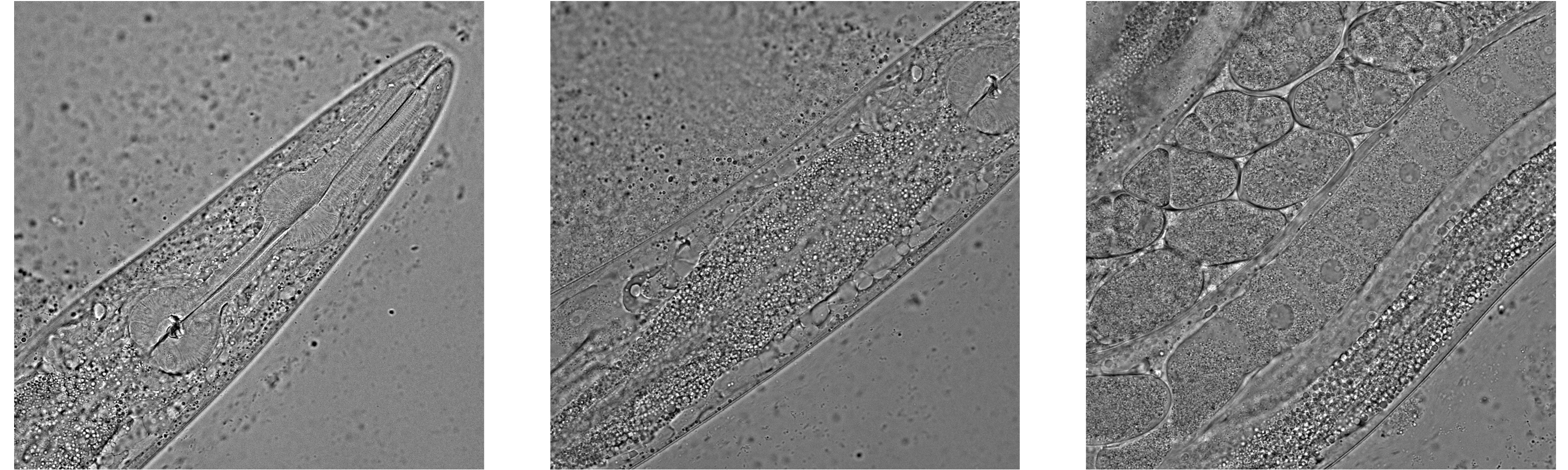

Seeing through a Caenorhabditis elegans, or roundworm, using a confocal microsocope, Jess Nash, 2024.

Order Is Only Abstract

What I’m Working On

Jess Nash

How can we represent microscopic bodies?

Let me rephrase:

How can we possibly represent microscopic bodies?

We have no direct experience of them. They’re too small, out of reach in our own sensory worlds. I couldn’t point to one, or describe how it feels between the fingertips. They are undetectable to the naked eye.

Enter apparatus: the microscope. With glass and light, we have found and refined windows into this invisible world.

What we see down there is a lot of chaos.

I’m a biologist. I’m also an artist. I was an artist first. Contrary to what you might think, there’s a lot that connects these two disciplines.

For my postgraduate research at the Department of Neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine, I spent hours peering through microscopes at brain cells, or neurons, of nematodes of the species Caenorhabditis elegans. They are tiny roundworms found in soil—and research labs—around the world. Though they are hundreds of millions of years removed from humans in evolutionary time, we have a lot in common with these animal cousins at a cellular and neural level. From studying them, we can learn about ourselves. Their bodies are transparent. To see inside, all one needs to do is look.

Look very closely, that is, through those glass and light windows of the microscope—to see those cells, all the cells at once, bunched together in the body in layers and layers.

How do we make sense of it?

I turn to abstraction: I don’t look for accuracy, but instead for some truth, or faithfulness.︎ I turn to abstraction: I don’t look for accuracy, but instead for some truth, or faithfulness.︎

As an artist, I’ve always been drawn to landscape painting. Wetlands and lakes interest me in particular, distant mountains and forests. I’ve often wondered what it means to truly represent these views. A painting can be plausibly realistic, but never accurate. There’s always too much there, and too much change. Any representation is a composite of instants chosen to capture, with the naked eye, an infinitely complex and ungraspable scene. I turn to abstraction: I don’t look for accuracy, but instead for some truth, or faithfulness. Not to the view itself—laden as any depiction will be with my choices and interpretations—but something in between, or in collaboration, with the natural world and my imagination.

In the practice of microscopy, just as in the process of painting a landscape, we compose, interpret, pick things out. We make sense of nature—of chaos.

Born in 1852, the groundbreaking neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal was an artist first. Growing up in Petilla de Aragón in northern Spain, the young boy drew images inspired by his memories and dreams. He wasn’t interested in what he could see and sense in his own world. The village’s austere walls bored him. In notebooks, he composed vast and elaborate scenes from history, of wars and saints, imaginary landscapes seeded from the surrounding Navarrese valleys. He scrawled loosely and compulsively, often coloring his drawings with bright unnatural pigments.

But it was a time and place for the classicist and the realist, for which he was unsuited. Worse, his surgeon father severely disapproved of art as a vocation. He gave his son no other choice but to pursue a path of rigorous science.

What a life for an artist.

Yet, the young Ramón y Cajal still found room for art, discovering unusual subjects that were hidden from the everyday. He developed a successful career as an anatomist, and found a place in the late 19th-century drive to decipher and document the structure and workings of the nervous system.

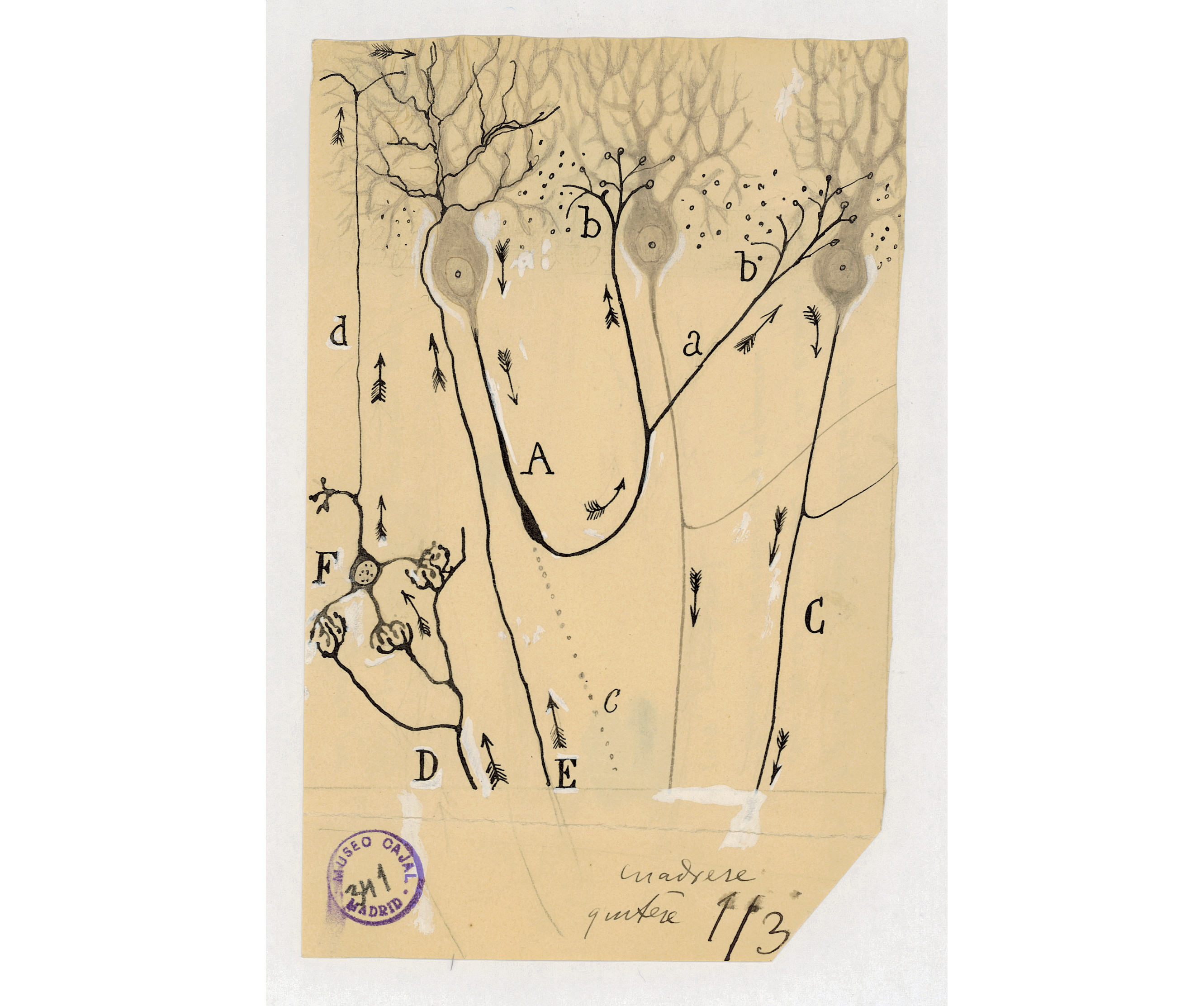

Back then, the understanding of the brain was underdeveloped. It was thought to be a continuous reticular web of tissue, not individual cells. For study, a scientist would cut out a thin slice of the gray matter; under a magnifying lens, it would appear as a solid, indistinct mass. Applying a treatment of dichromate, ammonia, and a silver nitrate bath could selectively stain—pick out—neural structures, revealing brownish-black long fibers creeping through down to the tips of every branch. With a few cells affected at random with each treatment, and the surrounding tissue rendered transparent, mapping the entire sprawl meant staining slices over and over, and putting the information together.

The resulting compositions looked like tangles of long, black threads, stretching out through the gray matter. Most scientists perceived one network throughout the brain—one thing all together, one continuous body.

Instead, Ramón y Cajal saw cells.

In these stained branches, he saw not continuity, but beginnings and ends. Not one long thread, not an unbroken network, but countless individual forms.

His drawings revealed statements about the world.︎His drawings revealed statements about the world.︎

He looked at the mess of tissue with the same gaze with which he’d looked at the countryside of his youth, and understood how to turn his irrepressible, boundary-breaking artistic sensibility to yet another world out of reach to the naked eye. The same speculative imagination that had compelled him to invent images of landscapes and heroes allowed him to intuit functions and relationships among individual cells of the nervous system. He constructed his own compositions accordingly, drawing what he saw, how he saw, with the precise hand of a trained anatomist—his father’s unintended gift to the artist—and opened up new ways of seeing neurons. His drawings revealed statements about the world.

Diagram showing the possible course of currents through the pyramids of the cerebral cortex, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, circa 1914.

Black Chinese ink, graphite, and gouache, 182 x 109 mm / 7. 1 x 4.2 inches (irregular). LC03068. Courtesy of Cajal Legacy-CSIC.

Over many years, Ramón y Cajal established more direct experimental evidence for his way of seeing: the Neuron Doctrine, the vision of the brain as composed of individual cells, a rejection of the continuous network. By the mid-20th century, microscopy and neuroscience had advanced to the point that his theory was indisputable. These days, we can look so closely at brain tissue that we can directly see the nanometer gaps between neurons. Ramón y Cajal’s neuron drawings are still widely admired as a landmark example of scientific representation and interpretation, and for their beauty.

What a life for an artist!

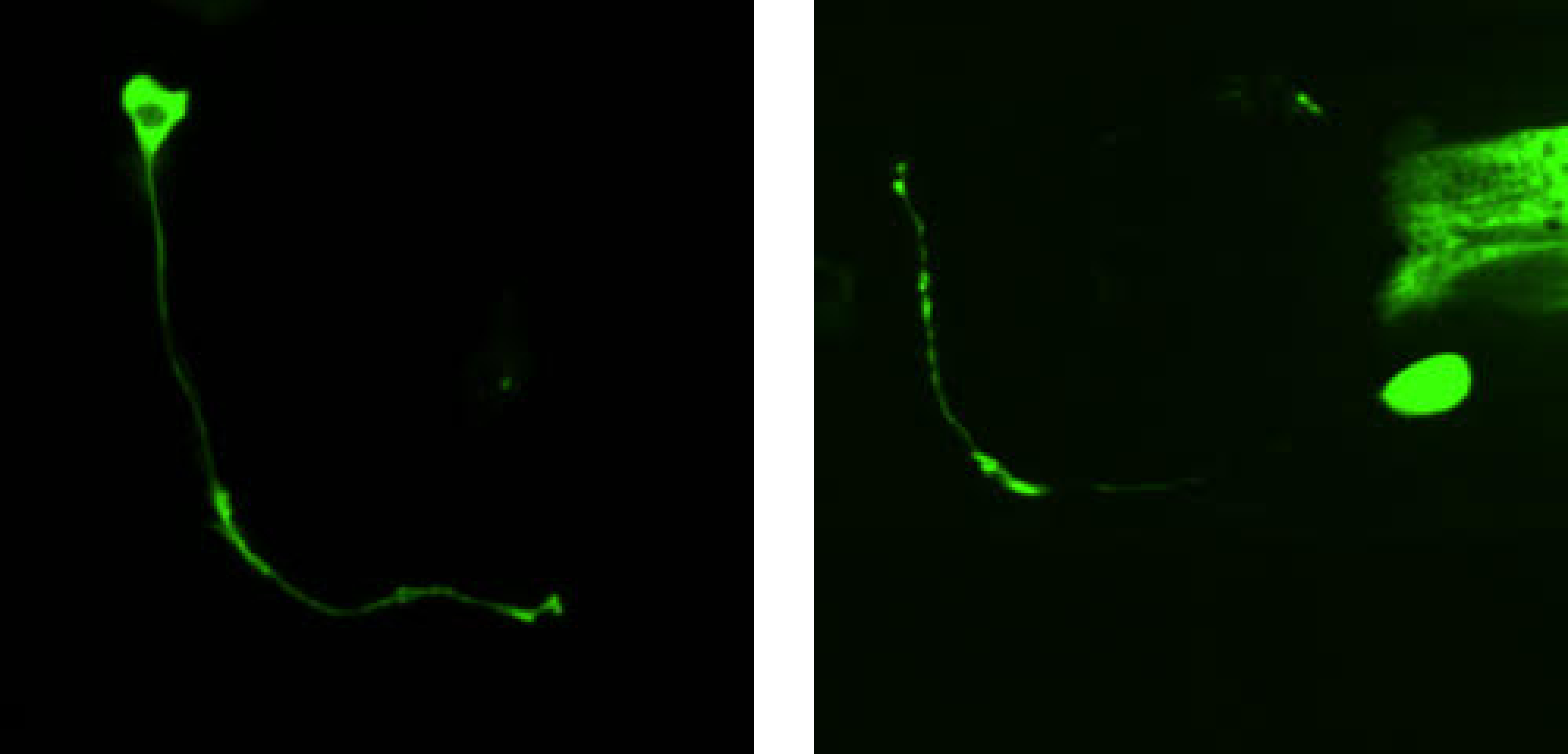

In the course of my own scientific work, almost 120 years later, it’s an everyday mundanity for myself and my colleagues to genetically modify organisms under study to express fluorescent “tags”—to set things up so that under a laser light, a microscope can show us, in bright unnatural color, exactly where a certain protein is in a cell, or where a certain cell is located in a living body.

In the world of our senses, a Caenorhabditis elegans appears as a white squiggle no larger than the comma in this sentence. You can see it moving if you look closely. For a routine session, I put one on a glass slide, and place this carefully in the jaws of my lab’s powerful microscope. I adjust the focus knob to get the low-mag lens to the correct distance. I engage the high-mag lens. There’s a second of blackness. Then the white landscape of the roundworm’s body is thrown wide across the adjacent computer monitor. I’m always taken aback by the sheer chaos there, all the colorless masses of organs and tissues filling the skin. Even 4,000 times magnified, nobody could tell its brain cells apart from the rest.

Under the surface, under many surfaces, this bright unnatural color hides in one cell.

I turn out the lights, turn on the laser. And—

Neuron in monomeric green, Jess Nash, 2024.

This is what one neuron of a Caenorhabditis elegans looks like to the naked eye.

Here, I have photographed one plane, then another, and another. Out of the stacks reassembled are these images. In a few seconds, top to bottom, the camera has captured pictures of a hundred planes, separated by tiny vertical distances from the last, fractions of micrometers. I bound the camera’s range when I see where the neuron comes out of focus at the extreme top and the bottom. In a few seconds, I photograph motion, volume, dimension; then, with a composite tool, still and flatten at will.

I wish you could see it living and moving. In real time, the neuron gives me the impression of a ghost: tranquil, silent, glowing green, floating a little—almost seeming to breathe. All alone in the dark…

Around it, pressing up on every side, are its neighbours and partners: other neurons in its network of thought and sensation, body cells, fluid. It appears to float because the whole body is shifting. It is surrounded by noise.

But in fluorescence, it is made quiet and solitary. Observed—pictured—it floats alone.

The gaze is made real. Life imitates art; we made it so.︎The gaze is made real. Life imitates art; we made it so.︎

To set one neuron apart this way is to actualize our conception of cells’ individuality in the real world, not just in our dreams. By modifying organisms with fluorescent tags, we extract one image out of the mass, as Ramón y Cajal did with silver nitrate stains and drawings of branching black bodies, leaving out all the cells’ surroundings. But now, we make it a biological truth; we materialize it. The subject’s own biology is imbued with interpretation. With this intervention, our look at the subject’s body becomes the body. The gaze is made real. Life imitates art; we made it so.

In the modern practice of science, this kind of work is always a means to an end, an answer to a question. Bodies are samples, and samples are paralyzed, then destroyed. I made these pictures for one reason: to observe the localization behaviour of a protein that helps to make energy for the cell, to tag it in green, and ask where within that particular neuron it tends to go and attempt to conclude what parts of the neuron demand energy. (It turns out: everywhere, every part.)

Humbled by the system’s beauty and complexity, I still master it. The scientific image, each made for its own reason, is a subjugation—of the body, of light and sight, of movement and breath, of chaos to control.

Scientific images tend to influence how we see and feel the phenomenon of the microscopic body. But different truths dwell in that scale. Even more so than in Ramón y Cajal’s time, accepted methodologies inescapably narrow our gaze. They restrict reality. Order is only abstract.

Art and the imaginary already, undeniably, reside everywhere in our knowledge of nature. And knowledge of nature resides in art. But striving toward perfection in representation will not create deeper meaning. Only a shift in understanding about what perfection is, and what it can reveal, can do that. This requires an experimental expansion of methods and tools: new ways of seeing the world itself.

When I look at the bright, moving neurons, I get the same feeling as when I look across a lake at a forest in mist. How do I follow that feeling? How can I strive to see neurons the same way I see that landscape, with all the changing, coexisting pictures, all the potential representations and different truths within?

Maybe you noticed a fleck of bright green floating by the neuron’s illuminated body. It is unattributable to the cell under study, and it catches my eye. What is it? A biologist might dismiss it as a stray signal; or it is noise, an anomaly produced by the apparatus or the preparation process.

This excites me. When I see it, I remember the rest of the body, the solidity of the surroundings that have been made by my manipulations into an empty background, the weight of the black part of the image, the cells that live and breathe around the neuron isolated in my gaze. I am reminded that unexpected things happen when I make an image with a microscope, as when I paint. Under the lens, or across the lake: Why are my expectations as they are, and what are their consequences? What do I see, and what do I miss?

For these questions, a sketchbook takes the place of lab notes. Is uncolored space a background, empty and impotent, or a solid and miscible surrounding, interacting invisibly with what I have attempted to pick out and isolate? Is it an extension of the object, into which it blends? Does it conceal parts of that object? How do I group flat surfaces by color to make sense of a dimensionally complex scene? How do my past experiences, my memories of images, bias that sense?

Realized in a painting, the sky behind—around—a forest is sometimes as solid as the trees. What if a fleck of green floated in that sky?

Seven sketches, Jess Nash, 2024.