︎Fragments of Fate: William S. Burroughs and his Cut-ups︎Alex Zafiris︎Fragments of Fate: William S. Burroughs and his Cut-ups︎Alex Zafiris

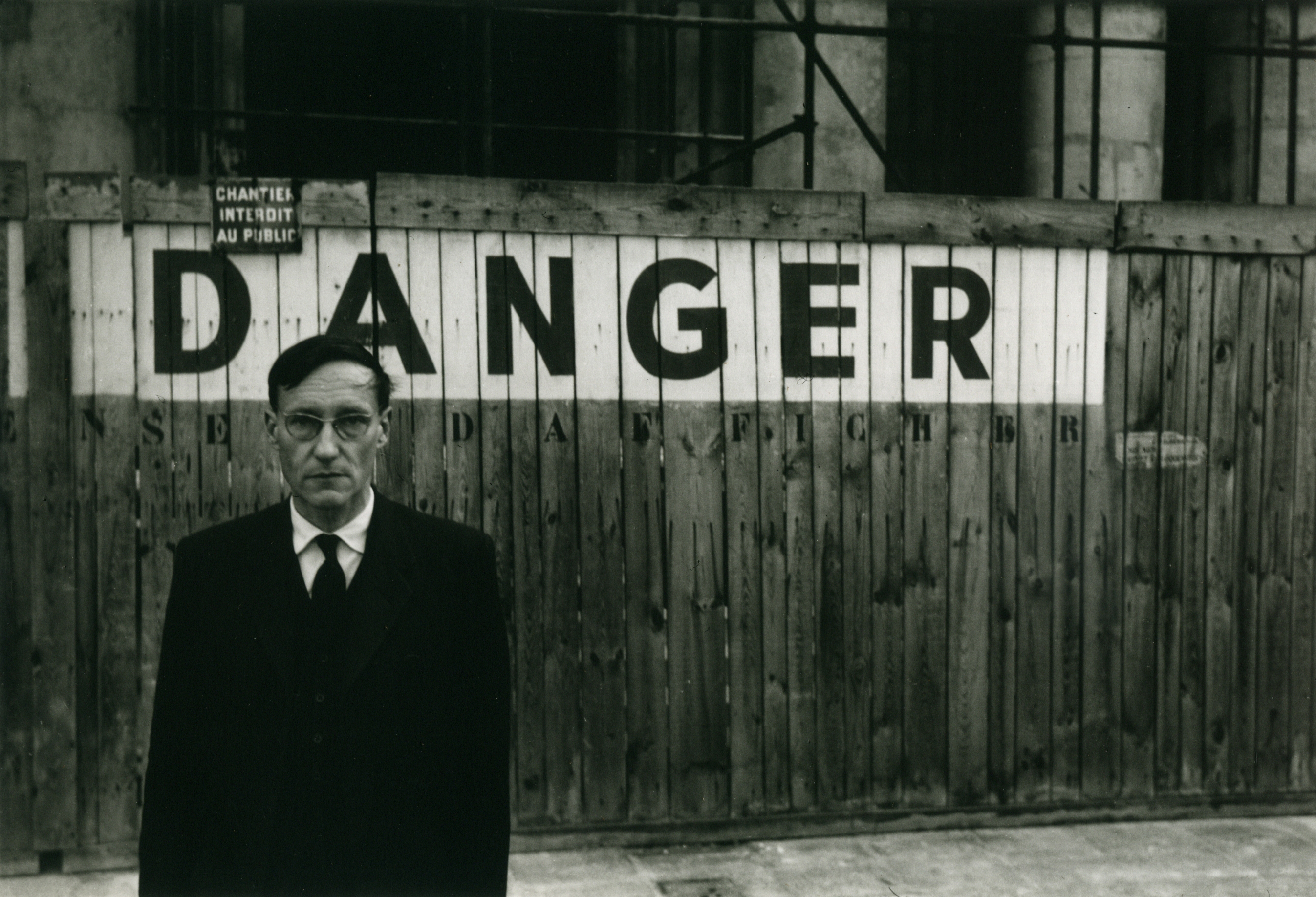

William S. Burroughs in Paris, Brion Gysin, 1959. The Miles Archive. Courtesy October Gallery, London.

Fragments of Fate: William S. Burroughs and his Cut-ups

Alex Zafiris

In 1954, three years after William S. Burroughs shot and killed his wife Joan Vollmer in Mexico City and got away with it, he went to hide out in Tangier. This was a hard stop on a previously listless, petty-crime filled life which, after the event of this sudden, nonsensical tragedy, flipped into nothingness. His step-daughter and son were taken from him. He prowled around Colombia and Peru in search of yagé, now more commonly known as ayahuasca, with the hopes of some kind of head-cleansing, hallucinogenic re-birth. He found it.

He was not yet a postmodernist icon. He had published the shrewd, autobiographical Junky a year before, on the persuasion of his friend Allen Ginsberg, who was convinced of Burroughs’ literary abilities from their extensive letter writing. Ace Books, a science fiction publisher in New York, had demanded continuous edits which he scratched out on his travels. Considered cheap pulp, it was finally printed as a “Two in One,” paired in a single volume with a popular noir novel, Narcotic Agent by Maurice Helbrant. Afraid of his parents’ reaction, Burroughs used the pseudonym William Lee. The book sparked minor attention, then disappeared.

Tangier was a place where a trust-funded, addicted white American could live as he pleased. His homosexuality was less of a social transgression, perhaps even a merit in the ex-pat social circles which included expulsed CIA agents, undercover gossip columnists, Francis Bacon, Tennessee Williams, and Paul and Jane Bowles. He stayed for four years, getting high (the police nicknamed him “Morphine Minnie”), sleeping with young local boys, performing entertaining “routines” for friends, and writing everything down. He met many of the louche characters later transposed into his fiction. He began to piece together these dissolute fragments of comedy, heartbreak, and dreams, but was derailed by his junk obsession. His parents arranged for him to dry out at a clinic in London; when he returned, his mind was bright and porous. He began to speak of spirituality, God, and learned of maktoub, Arabic for “it is written,” or “it is destined.”

Jack Kerouac, Alan Ansen, Peter Orlovsky, and Ginsberg arrived ashore with the intent to help him shape these scattered texts that piled high everywhere in his hotel room. Together, they gradually began to create Naked Lunch, although they all ended up rejecting the paranoid neon hum the work produced. They disbanded bitterly, and he kept writing, racing through a jaunt to Copenhagen and Denmark, landscapes so contrasted to Tangier that he fled back, only to find that whatever had been there for him had slipped his grasp. Faced with his own void, he spent days in wretched turmoil, attempting to sublimate emerging memories of childhood sexual abuse, and vowing to re-enter psychoanalysis. He located a Freudian analyst in Paris, crammed hundreds of loose manuscript pages into a suitcase, and left.

︎He began to speak of spirituality, God, and learned of maktoub, Arabic for “it is written,” or “it is destined.”

Ginsberg, Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso were already there, settled in at a fleapit no-name hotel at 9, rue Gît-le-Coeur on the Left Bank. Most of the guests were young Americans, in exile from their country, living in near poverty to exist freely. Burroughs reconciled with his friends and made new ones, a much more artistic crowd whose connections introduced him to Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Céline, but also landed him back on junk. By now, Ginsberg was famous for Howl, but the term “beatnik” was already derogatory, and hurled at them often. Maurice Girodias, who ran Olympia Press, was covertly publishing banned books—Lolita, Story of O, The Ginger Man—but refused to touch Naked Lunch. On the strength of his newfound notoriety, Ginsberg persuaded the Chicago Review (of the University of Chicago) to run an excerpt of it in their spring 1958 issue. The reader response was an explosion of fascination and hate. The second chapter followed in the fall issue, and more was planned for the winter, but members of staff resigned, and the University shut everything down. Resources were pooled, and all the obstructed work was printed in a new independent journal, Big Table. But the U.S. Post Office refused to distribute it on grounds of obscenity, and a highly publicized court date was set. Seduced by the controversy, Girodias changed his mind, asking for the complete text in order to release the novel immediately. In his rat-infested hovel, a strung out Burroughs pulled his suitcase out from under his bed and—again, with the help of friends—flung together what would become Naked Lunch.

Room 25 of the hotel was occupied by another Tangier runaway, the Canadian artist Brion Gysin. He too had been relentlessly rejected from countries, organizations, and groups (most devastatingly, from the French Surrealists, prompted by a sour André Breton), and spent his time painting and reading. An interest in the supernatural and the occult streamed through his ideas, an impulse for mythology, code, and scripture; he told outrageous, exaggerated stories. He and Burroughs had met before in Morocco, but were uninterested. Thrown together again by chance, both of them now shunted onto different paths, they found each other. Gysin was practicing calligraphy, pulling and shaping imaginary language into patterns on a canvas, shifting towards a physicality of the written word. Burroughs would sit in the corner and watch him work, either high or desperately trying to get clean again; being on junk shrink-wrapped his world, gave him an easy set of rules to follow and a sense of power, until it turned and took him hostage.

This constant bowing in and out of reality had refracted through him since he was very young. His mother was a superstitious woman, as were the Irish help she employed at their St. Louis home. As a child, he had believed in magic, and had experienced charming hallucinations, but at night, he had been terrified of the dark, suffering recurring nightmares. His older brother, Mortimer Jr., was staid and square, forever dispatched by their parents to bail him out—including from jail in Mexico City for murder. While Ginsberg and company were sufficiently drawn to notions of the subconscious, queerness, and collective thought, nobody aligned with Burroughs as Gysin did on the subject of unexplainable forces. Both men were simultaneously outraged and motivated by their outsiderness. Their pursuit of the paranormal and desire to intercept the social matrix of conformity was unsentimental, merciless, and coldly hilarious, even leading to an interest in Scientology. At one point, Burroughs became convinced that an “ugly spirit” had possessed and led him, on that terrible day, to suggest that Vollmer put a glass on her head for him to shoot, only to miss. A feeble attempt to abdicate responsibility, but characteristic of a haunted, anguished search for the unsayable and unresolvable. He could never reconcile with this event—though he would occasionally attempt to explain it—and nobody will ever forget it.

William S. Burroughs in Paris, Brion Gysin, 1959. The Miles Archive. Courtesy October Gallery, London.

It was October 1959. Burroughs was now feeling a push from the publication and uproar Naked Lunch was receiving. He had begun The Soft Machine, the first of what would become the Nova Express science fiction trilogy. These initial pages also came from the suitcase, coffee-stained and cigarette-burned from late nights in Tangier. Gysin showed him an accidental discovery: While slicing up mounts for artworks on his table, he had pressed too deeply and knifed off paragraphs of the New York Herald Tribune that lay underneath. Seeing these newspaper fragments isolated, he pushed them together in a different order, randomly creating new sentences and words. The effect—back then, and equally if you try it now—has a chilling efficacy. Snippets of bad news, disastrous events, political scandal and entertainment run together with an alarming sense of truth and urgency. Age-old, calcified turns of phrase are broken apart, neutered, and meaning flashes with new threat. Right away, Burroughs saw how this reflected the texture of own perceptions and experiences. His obsession with junk—the ecstatic feel of it and the violent, juxtaposing despair of it—was his direct contact with the systems of addiction that create the illusion of control. He wrote to Ginsberg: Junk is one of the most potent instruments of EVIL LAW. Drugs, sex, money, and power create dependency, and function to repress and manipulate the masses. Without these, or faced with the threat of losing them, withdrawal sets in. (In 1975, he would tell Studs Terkel: “I was struck by some pictures of Nixon during the Watergate. He looked just like a sick addict. The power falling away from him.”)

Weeks of experimentation followed, using his own work and different texts (running from magazines to re-typed passages from other writers such as Aldous Huxley), trying smaller and larger cuts, fold-ins, and bringing in friends to play along. Corso left abruptly, concluding that it was nothing but “machine-poetry.” Fights began to break out again. But Burroughs reminded everyone, as he would for the rest of his life, that “The Waste Land was the first great cut-up collage,” noting T.S. Eliot’s references to lines from dozens of other texts, both of his time and ancient, running from the Bible, Geoffrey Chaucer, Lord Byron, W.B. Yeats; laying them side by side, clashing their voices, muting their imagery, disrupting their sound, all to construct a tone and feel of a bleak and overcrowded modern existence, frazzled and directionless after the war, a bitter re-birth. (Much later, Burroughs would meet Samuel Beckett, who accused him of stealing other people’s words, to which he responded: “Well, the formula of one physicist is after all available to anyone in the profession.”) Over in New York, Jonas Mekas had gotten his hands on a copy of Big Table. Electrified, he wrote in his diary, “Burroughs is the first (to my knowledge) to write absolument moderne. All the techniques of modern writing here are perfectly integrated. [James] Joyce is already dissolved. Hence the unhampered spontaneous flow, the unpredictability of form, freshness, aliveness—the nakedness of Burroughs.”

His intense astuteness about the world came not just from a brilliant, outcast mind but from an insider’s view of the bourgeois life. His grandfather had patented an adding machine which became extremely successful. His uncle was Ivy Lee, the public relations pioneer who worked for the Rockefellers. He studied English at Harvard, but his stifled queerness ate away at him. He always had an unnerving, intimidating vibe. Women did not take to him, other than the freer types he met later in New York. But people were intrigued. His reputation, even before writing, was of a strong-minded, take-no-prisoners character with very traditional Southern elegance and manners. This contrast allowed him to infiltrate his areas of interest—the small-time crooks, thieves, conmen, the lost and forgotten people of society—and report back. He saw that their hopelessness had frozen and hardened into rage and self-abuse, and he understood exactly why, what forces kept them there. His lifelong hatred of the police stemmed from witnessing their indulgent cruelty towards the vulnerable—not because his own pleasures were mostly illegal. At the same time, there is a steely-eyed amusement in these pursuits, an addict’s rationale. He was not a savior. He was deeply aware that politeness and hipness can also be forms of power and control. This mix of above-and-below ground, of privilege and poverty, violence and protection, narcissism and care, results in what Mary McCarthy called an eagle-eye view, a kind of “statelessness.” Of Naked Lunch, she wrote: “The book is alive, like a basketful of crabs, and common sense cannot get hold of it to extract a moral.”

The cut-ups brought this expansive field of vision to a much higher level. Despite—or as he might have argued—because of his junk obsession, Burroughs’ antennae were highly tuned. They were a perfect technology to corrupt the rhythm, syntax, metaphor, and tone of socialized narrative and speech, using only a pair of scissors and sleight of hand. They not only fortified his voice, but expanded his ideas on invisible influences. He kept diaries full of thoughts regarding coincidence, serendipity, and fate, and created scrapbooks of collages. In his 1965 Paris Review interview, almost in a foreshadowing of open-source A.I. language models such as GPT-3, he explains: “Any narrative passage, or any passage, say, of poetic images is subject to any number of variations, all of which may be interesting and valid in their own right. A page of Rimbaud cut up and rearranged will give you quite new images. Rimbaud images—real Rimbaud images—but new ones.”

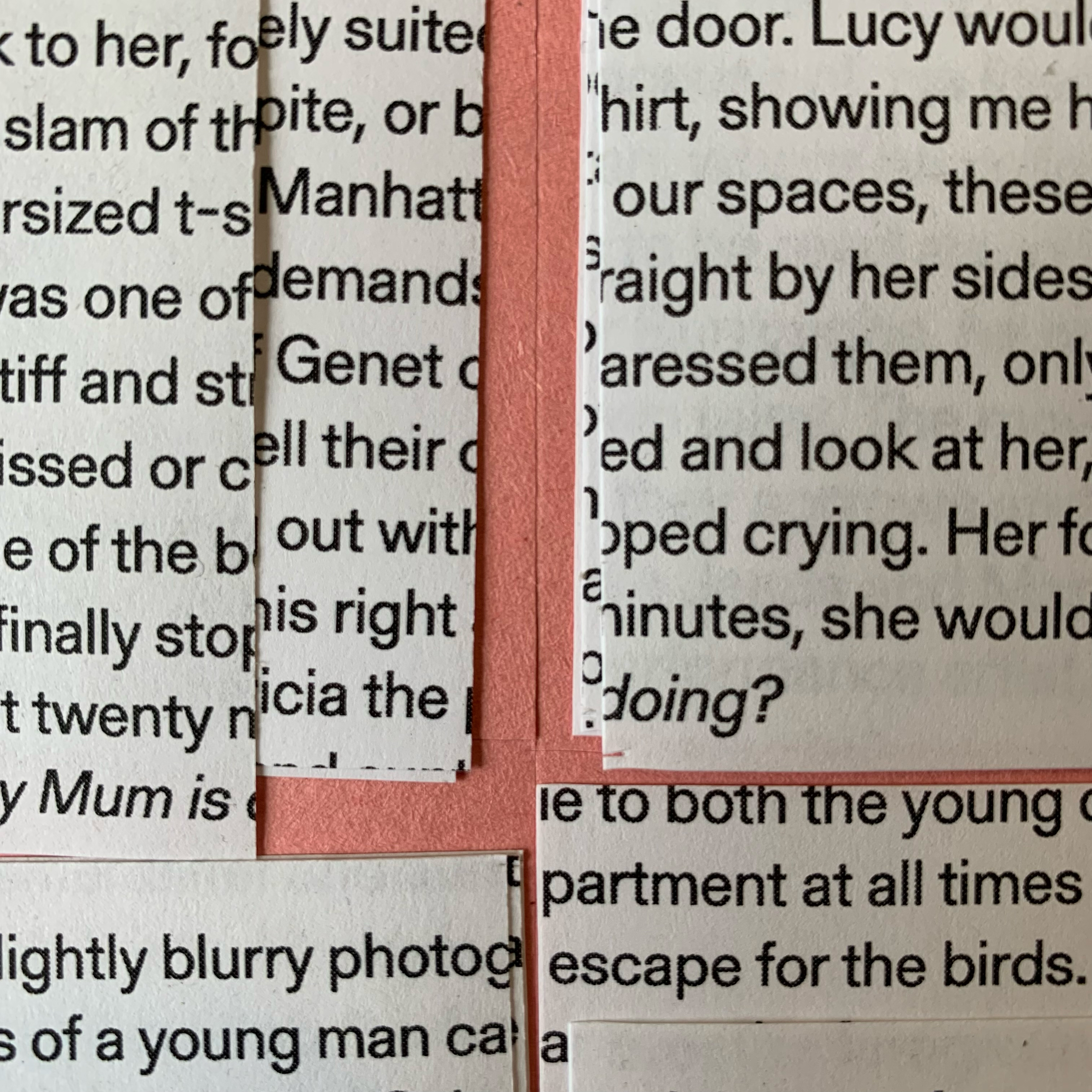

Cut-up of “The Unfated” in Gerstner-Programm, Alex Zafiris, 2022.

The Soft Machine (1961) led to The Ticket That Exploded (1962) and Nova Express (1964), the most noir, compulsive, and smutty science fiction trilogy ever published, with long passages of cut-ups. At once beautiful, shocking, and inscrutable, Burroughs blows up the future as a wretched landscape of brutality and baseness, run by savvy pushers and criminals let loose with a terrible freedom. The writing echoes the chaos and logic of dreams, pricking the subconscious of every reader with oblique, distant recognition, forcing them to become an anxious presence within the text itself. From The Soft Machine (an euphemism for “the body”):

“His plan called for total exposure—Wise up

all the marks everywhere—Show them the rigged wheel—Storm the Reality Studio

and retake the universe—The plan shifted and reformed as reports came in from

his electric patrols sniffing quivering down streets of the earth—the reality

film giving and buckling like a bulkhead under pressure—burned metal smell of

interplanetary war in the raw noon streets swept by screaming glass blizzards

of enemy flak.”

Burroughs still feels very alive. His voice, persona, and influence continue to flow through modern life. With him emerged a new, dissonant cultural power. Words were no longer texts, they were images, sounds, signs, tools to pry open new worlds. His cut-up method is interdisciplinary: Early adopters were Bob Dylan, The Beatles, David Bowie, Lou Reed, and later, Kurt Cobain, Sonic Youth, Thom Yorke, Laurie Anderson, Throbbing Gristle, and Gus van Sant. He collaborated with Keith Haring, George Condo, Jim Jarmusch, and David Cronenberg; he also became an artist later in life. He became a queer icon. Patti Smith claims that he was responsible for the entire punk rock movement. Writers he has influenced include Kathy Acker, Lidia Yuknavitch, Angela Carter, J.G. Ballard, and William Gibson. Junky, as well as Naked Lunch, continue to be essential reading.

︎They were a perfect

technology to corrupt the rhythm, syntax, metaphor, and tone of socialized

narrative and speech, using only a pair of scissors and sleight of hand.

Towards the end of his life, he was a celebrity, a living legend, a hipster in a suit. He never truly kicked junk. In an interview with the BBC in 1982, the host John Walters asks him about the method, whether serendipitous, random occurrences held meaning, or were a kind of message, such as seeing an advertising logo that triggers an old memory. He answers, “These juxtapositions between what you are thinking if you’re walking down the street and what you see—that was exactly what I was introducing [with the method]. You see: Life is a cut-up. Every time you walk down the street or look out the window, your consciousness is cut by random factors. And then you begin to realize that they are not so random, that this is saying something to you.” Walters then brings up Arthur Koerstler’s theory that coincidence is actually revealing a hidden web of reality. “Absolutely,” replies Burroughs. “There’s no such thing as coincidence.”

You can try your own cut-ups with online generators here and here.