︎Persona Poem︎Alex Zafiris︎Persona Poem︎Alex Zafiris︎Persona Poem︎Alex Zafiris︎Persona Poem︎Alex Zafiris︎Persona Poem︎Alex Zafiris

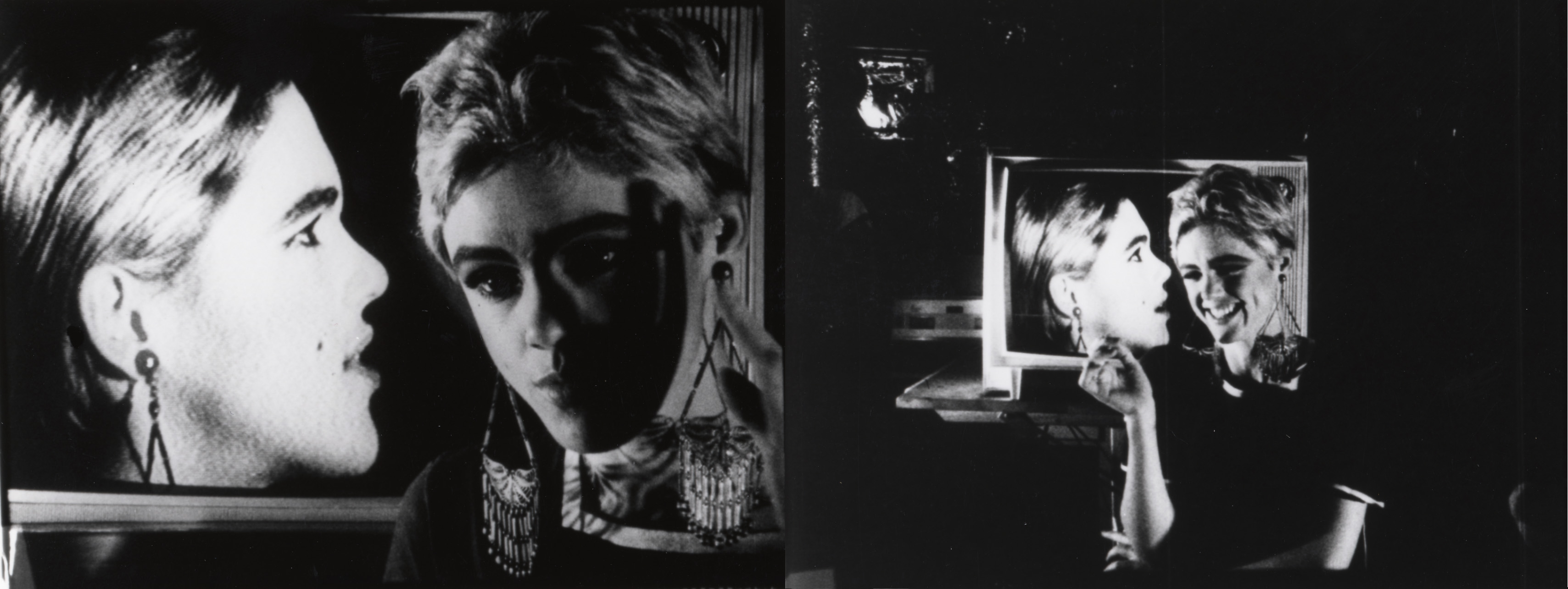

Andy Warhol, Outer

and Inner Space, 1965. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 66 minutes or 33

minutes in double screen © The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a

museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Film still courtesy The

Andy Warhol Museum.

Persona Poem

Alex Zafiris

Persona Poem

Alex Zafiris

I met Edie at an opening. In any

situation her physicality was so refreshing that she exposed all the dishonesty in

the room.

—Robert

Rauschenberg, from “Edie” by Jean SteinIn July 1965, Norelco delivered their new EL 8015/II video camera to Andy Warhol’s Factory on East 47th Street. Heavy, unwieldy, peculiar, the slant track machine retailed at just under $4,000. Noone was buying. They figured an art star would find a fresh use for it. The conditions for the loan were: An artwork, a promotional party, an interview in Tape Recording magazine.

Warhol had already made over 50 films. Among them, “Sleep”, “Kiss”, “Empire”, and his “Screen Tests”. These featured his friends, people he found fascinating just as themselves. If they did not appear in front of the camera, they were behind it. Co-creating a reflected image was his conduit to intimacy. He called them home movies.

In March of that year, Warhol met 21-year-old Edie Sedgwick, only weeks after she had arrived in New York from Cambridge, MA. She had just experienced the loss of two brothers, Minty and Bobby, to suicide. She herself had been in and out of institutions since a teenager. Her aristocratic, abusive, neglectful parents—whom doctors had advised not to have children, due to their own behavioral disorders—imprudently supplied her with a trust fund.

Perhaps this mix of profound grief and mythological promise of the city helped produce Sedgwick’s modern energy. She and Warhol immediately recognized their desires in each other. He wanted uptown glamor, she wanted artistic credibility. For a frail middle-class boy from Pittsburgh, this meant acceptance and money. In refusing to play straight, passing in the higher echelons of society meant true success. But Sedgwick’s intelligence had been simultaneously suppressed and intensified by those systems. Her self-starved body could wear the latest fashions, which she could afford; she ended up iconizing dance stockings and short silver hair. She could forgo work, run riot, get ‘sent away’ for a spell, and come back. Many joked that mental hospitals and the Factory weren’t too dissimilar, just a different context. But what she intuitively understood in Warhol and his work was freedom, a space to be. Her charisma was not beauty. It was innovation.

Andy Warhol, Outer

and Inner Space, 1965. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 66 minutes or 33

minutes in double screen © The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a

museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Film still courtesy The

Andy Warhol Museum.

They became inseparable. Very quickly, he put her in front of his lens. Bit parts at first. Sedgwick was very open about her darkness. Given the time and her conservative heritage, this was both disarming and charming. Despite the torment, she surrendered with humor: their first full film was “Poor Little Rich Girl”, an hour-long, adoring haze that watches her wake up, get dressed, and talk on the phone. A sincerity flowed through her, opened a kind of erotic liberation. It made the suffering sharper, but the light even stronger. Although shining bright, this truth was amoral to most. She would easily lie, cheat, overspend, forget, dismiss. Staying ablaze meant a refusal of everyday reality. But on screen, she could exist untouched, purely creative, in a liminal space. She radiated instinct and vitality within his nihilistic, flat surface.

︎Her charisma was not

beauty. It was innovation.︎Her charisma was not

beauty. It was innovation.

By the time the Norelco was unboxed and set up, Warhol knew the fragmented design of her psyche. Video was yet to be used by artists. It did not require fastidious lighting, nor a second sound recording. The results were instantaneous—no waiting around, compared to his experiences with the Bolex or Aricon. Without these restrictions, this new machine led him to build a split-screen structure into a new work, “Outer and Inner Space”, one of the earliest known uses of this format.

It was August, boiling hot. She sat first for a half hour video shoot, framed in close-up profile and very still, looking upwards and speaking calmly, as though in recital or prayer. He then ran this back on a television monitor, and had her sit in front of it, at a more open angle, to the right of her own image. He then filmed her again on a 16mm, 33-minute reel. Out of ear-shot, someone asks questions, engaging her in a conversation which provokes both joyful and painful responses. She looks ahead behind the camera, never directly at us. In contrast to her serene face on the monitor, she is constantly in motion, giggling, teasing, reacting, defending. This procedure of double filming happened twice, with one zoom slowly in, and the other slowly out. The final work is exhibited with both film reels adjacently whirring and eclipsing one another, pulling towards and away from her while the video on the monitor—a few minutes shorter than the reels—flickers out separately. The effect is of a woman’s internal and external frequencies, the private and public tension exposed in cross-currents of emotion and speech.

Warhol’s films are almost always pre-narrative. For viewers unwilling to float in that uncertainty, a conflict arises. Rejection and projection ensue. But those who accept that lawlessness find a very pure pleasure in the picture. Wherever she went, Sedgwick effortlessly controlled the room. Captured on any kind of recording equipment, she dominates the properties of the image. This alignment of physical and representational life is the result of a woman who understood herself and others in an unusually fundamental way; this in tandem with her acute sense of the disappearing old and the edge of the new. Hardly anybody could grasp Warhol’s work at the time, nor explain his pull. It was too easy and fun to look at a huge silkscreen painting of a Campbell’s Soup can. It was even easier to create (and re-create) it. Sedgwick not only understood his vision, but embodied it with great power, marking its existence off the screen and canvas. Without her, our understanding of him would be much more limited. “Outer and Inner Space” is the highest point of this connection. Without the help of the Norelco, it may never have been captured quite in this way. Watching her profile fade on the monitor behind her as she talks is devastating. He articulated the technology, but she was the language.

︎Captured on any kind

of recording equipment, she dominates the properties of the image.

By November, the Sedgwick-Warhol romance was ending. She was becoming too difficult, too unpredictable, too high. He had already secured all her rich contacts. Worse: She was more desired than him. They broke apart. Other work was shown at the promotional party. The camera was returned; it never sold.