︎SEED︎Tracy Xinran Li︎SEED︎Tracy Xinran Li︎SEED︎Tracy Xinran Li

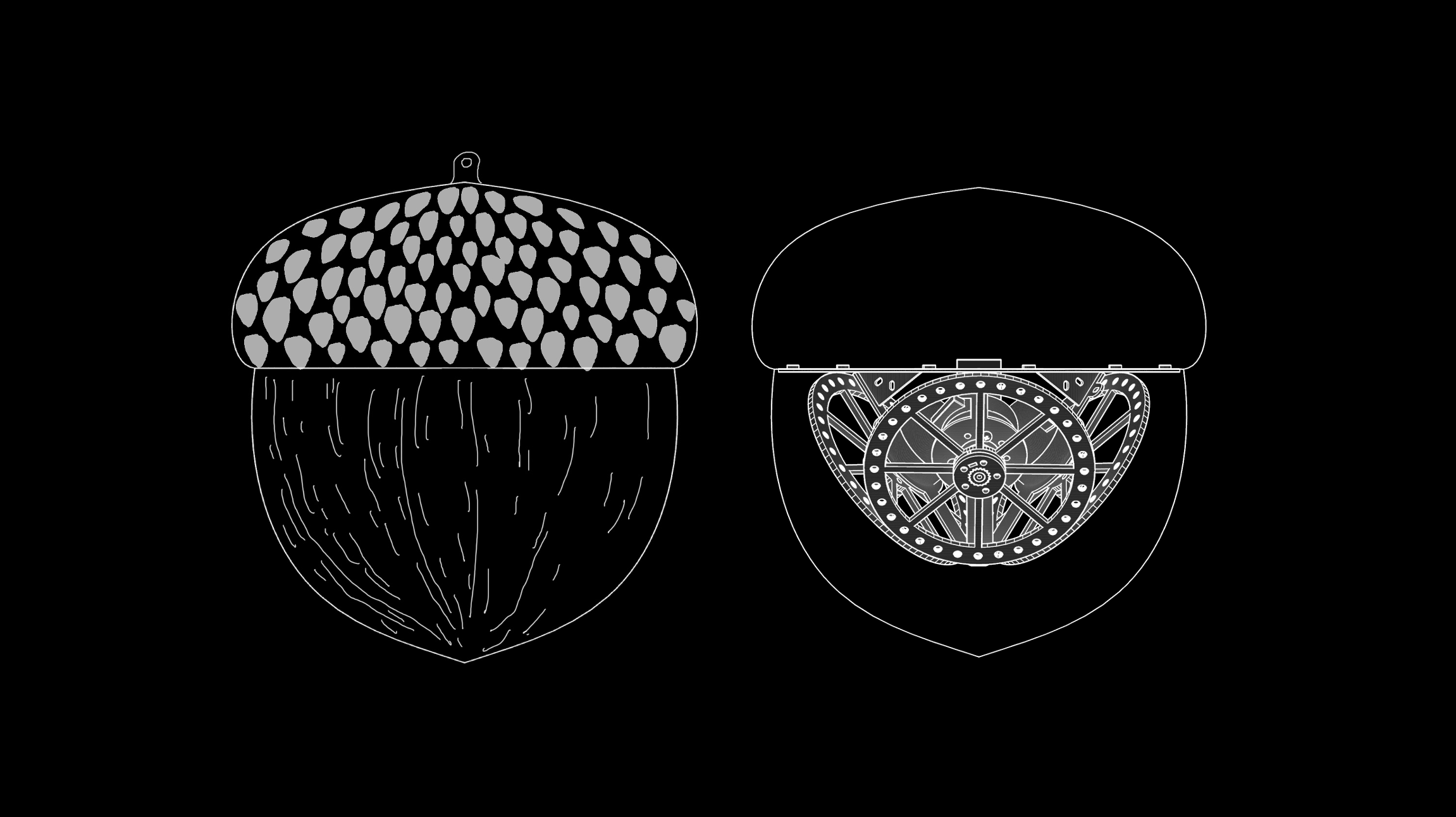

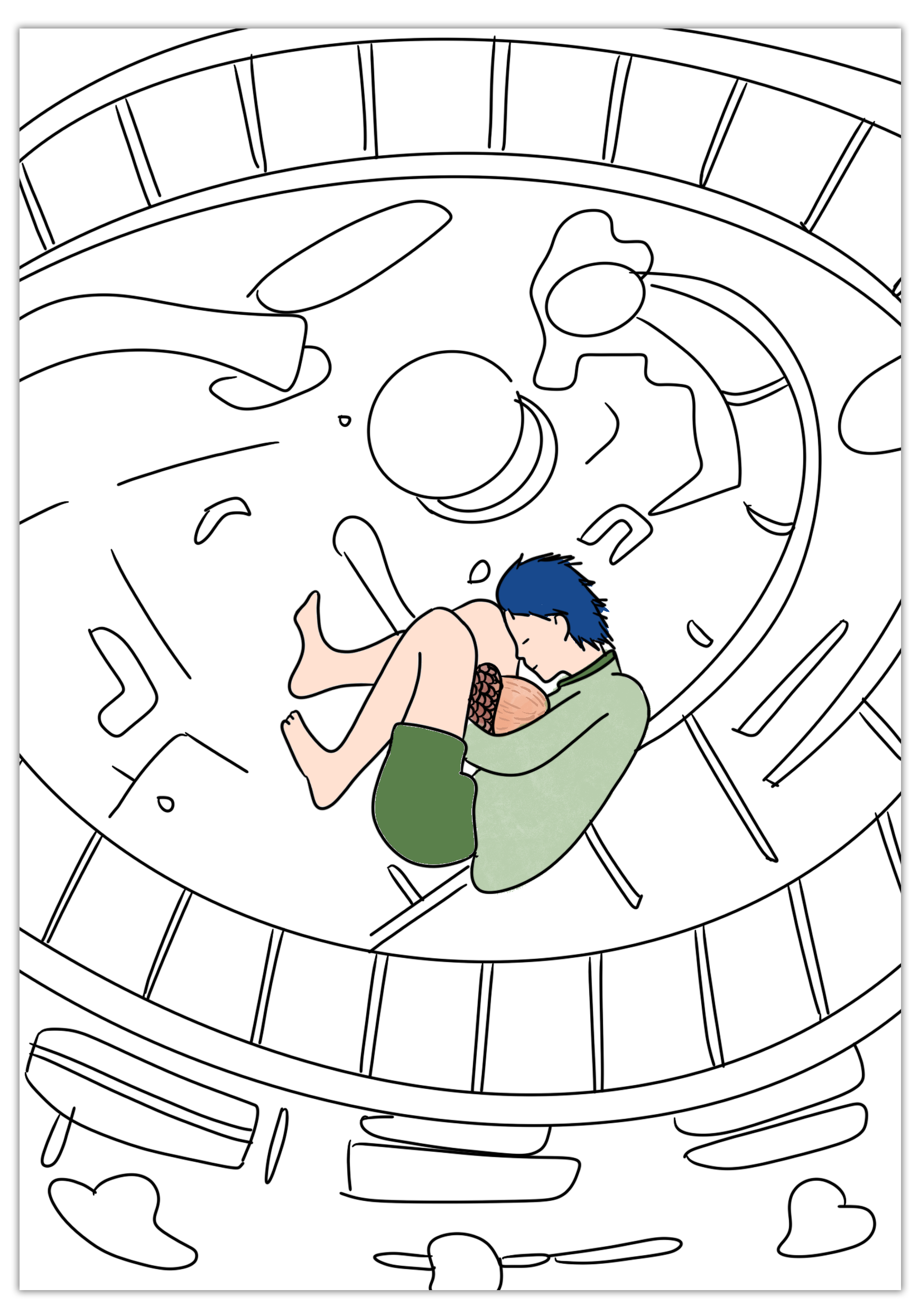

Diagram for SEED. All images by Tracy Xinran Li, 2024.

SEED

Tracy Xinran Li

I study architecture and computer science. I’m a senior now, but SEED is a project from my junior year. I’m from Nanjing, in China—this is my first time living and studying in the United States. I feel I can relate to a space traveler, in the sense that we are both very far away from home.

With architecture, what attracts me the most is physical space and its components, like light, even air circulation; the materiality, and the way a body can navigate within it; and the feelings and emotions this can provoke. Computer science feels more like a tool: I am able to use technology like virtual reality, augmented reality, and computer graphics to design interactive systems. Through these, I can explore how the body can interact with those ephemeral properties.

I heard so many amazing things about Dana Karwas and Ariel Ekblaw’s class, “The Mechanical Artifact: Ultra Space,” that I begged Dana to take it. It was one of the few courses that combined my technical and design skills to create something I’m really passionate about. There were about 10 of us, a mix of grads and undergrads. That’s where I developed the idea of SEED.

SEED stands for Space Earth Embodiment Device. It functions as a compass for the space traveler. As astronauts orbit their planet, floating freely in a zero-gravity shuttle and disconnected from nature, they often lose their sense of direction. If they hold SEED in their hands, it will rotate and point toward home.

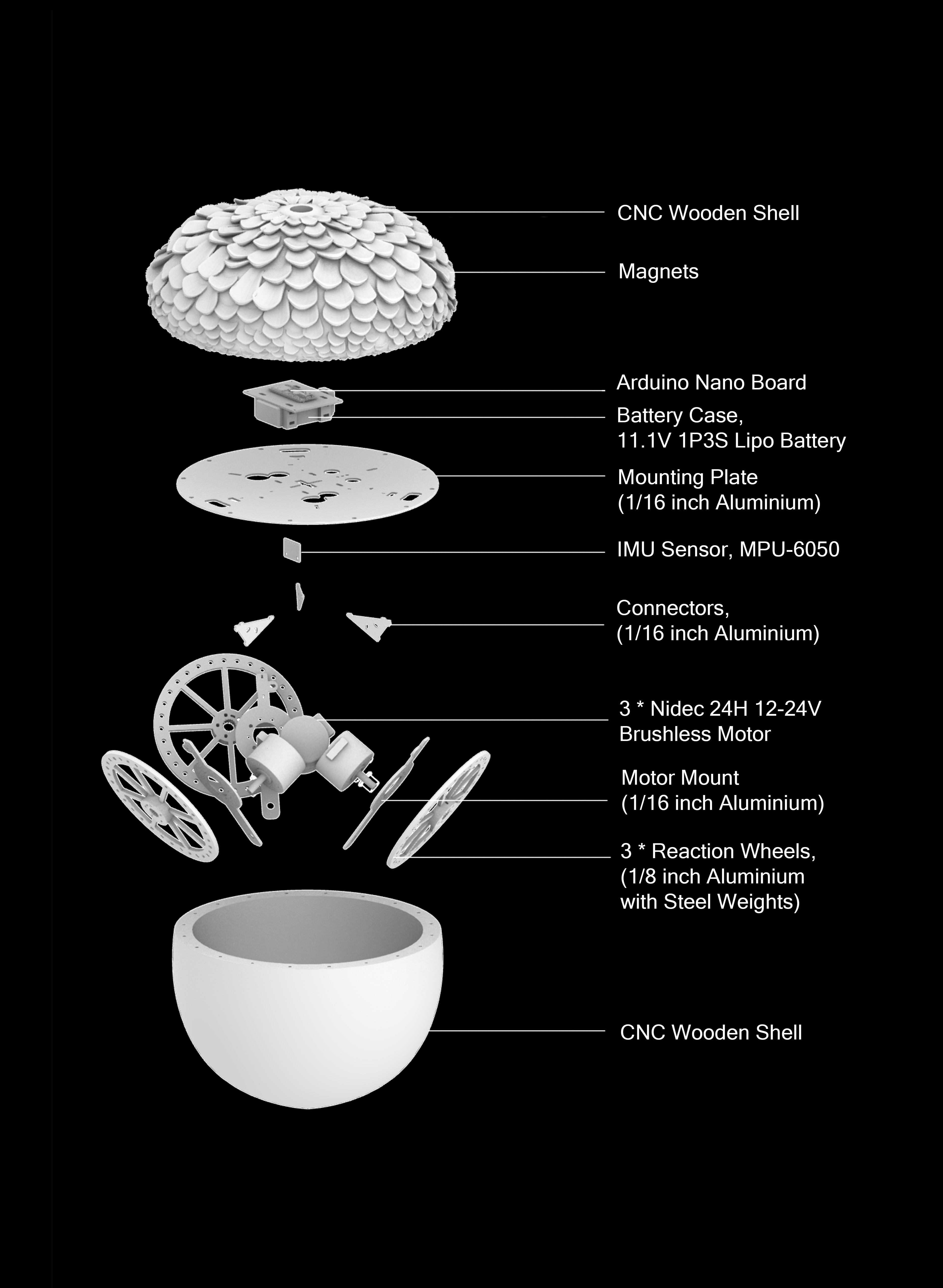

Exploded axonometric drawing for SEED.

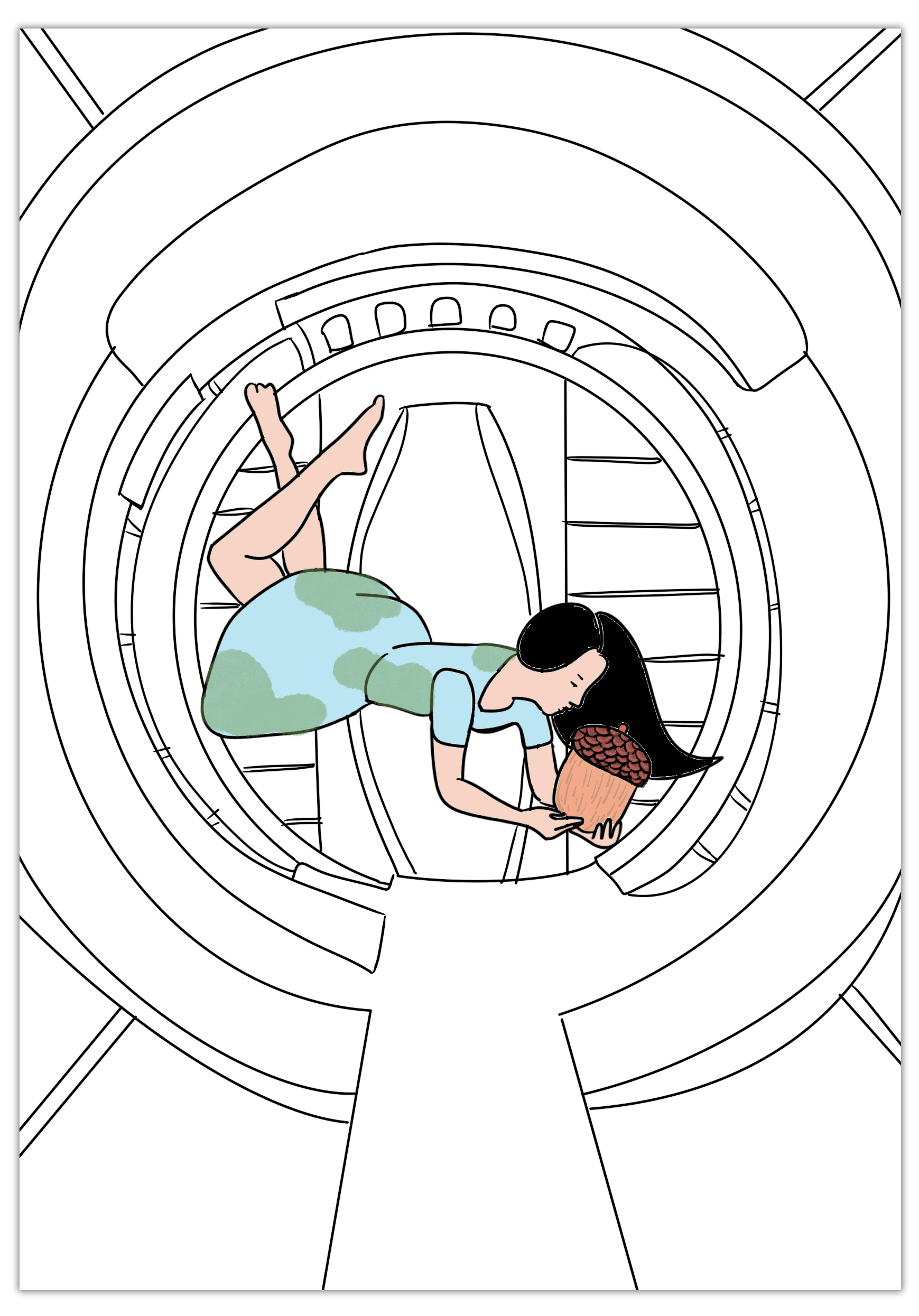

A space SEED pointing the way home.

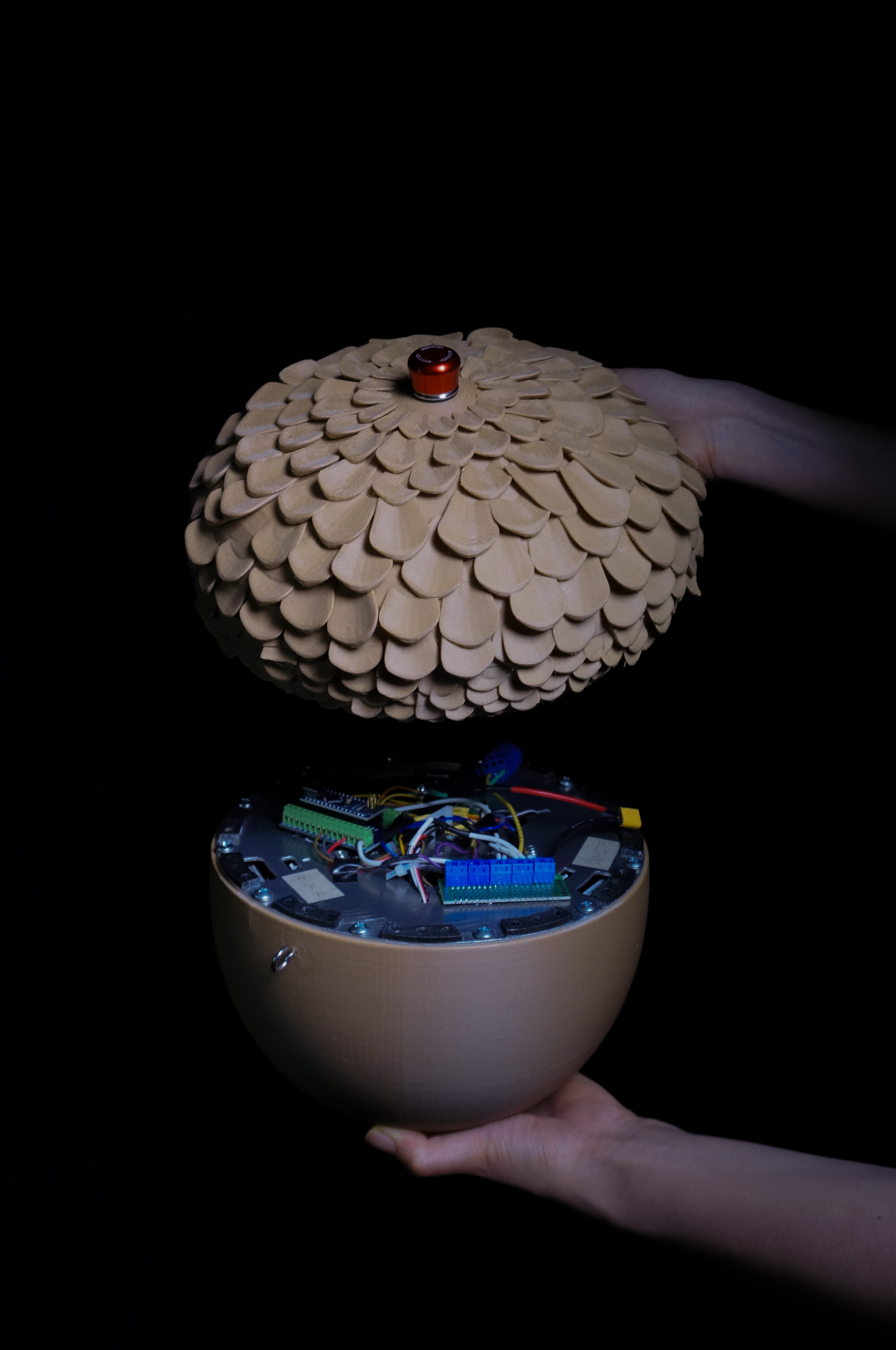

Inside is an intricate internal structure, almost a miniature spacecraft, cut from aluminum and steel. An IMU sensor records angular displacement; three reaction wheels, orthogonal to each other, keep SEED turning toward Earth. This mechanism is encased in a wooden shell, which takes the shape of an acorn—the seed of an oak tree. It smells like a forest. When holding it with both hands, you feel its weight, heaviness, and gravity, due to the resisting force generated by the reaction wheels.

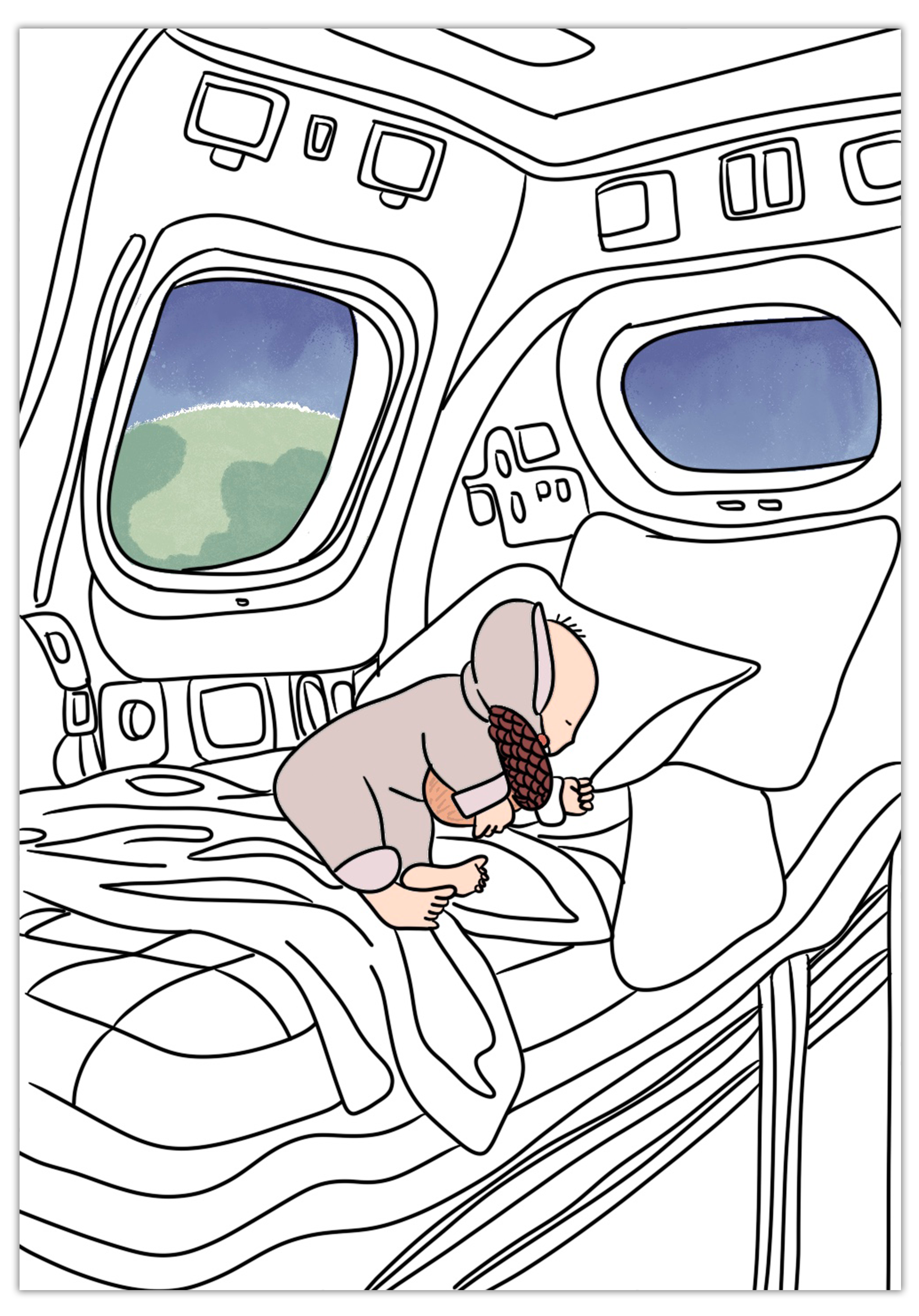

SEED is a metaphor for the traveler. It also wants to go back home. It remembers gravity. It is grounding, centering, and calming. And there will be new generations. If a baby is born in space, it would have different memories about SEED, and about Earth. In that sense, SEED would become part of their identity. You would not be an Earth human, or space human—or I suppose you could be half Earth human, half space human. Which is something I feel myself, because I feel very Chinese, but part of my identity is American now, so I’m also in this half-half situation.

Woman, baby, and man with SEED.

Very early on, creating SEED felt like an impossible task, but I also really wanted to do it. Inspiration came during a random dinner conversation with Kaifeng Wu. Putting it together was very exciting, and also scary. I kept feeling that it was a bit out of control. There were so many things I had no idea how to do, for instance using Rhino in 3D to view all the models. I had done some robotics before in high school, but design is so intricate and complicated. I frequently turned to Wai Hin (Alfred) Wong for mechanical engineering. I got a lot of help from the Yale Center for Engineering Innovation and Design (CEID), particularly from Joseph Zinter. He taught me how to solder things, and how to connect the circuit. He also pointed me to a lot of peer advisors at CEID. Nathan Burnell, the assistant shop manager and instructor at Yale School of Architecture, helped so much, because I cut all the metal pieces myself, down in the sub basement. I didn’t know how to use the machines, and everyone was super patient and walked me through the process. There was a lot of trial and error.

SEED prototype 3.0.

All the work I’m doing now has something to do with the sky and cosmology, and home, intimacy, time, distance, and memories. I’m interested in harnessing the unique qualities of new media—all the facets that traditional media and the real world cannot offer. I want to encourage a conversation about what is real, and what is not—and, does this difference matter? To explore this more, I’m taking a new class, “Creative Embedded Systems,” with Scott Petersen. He is also advising my senior thesis in computer science, which is a multimedia performance involving dancers, simulated sunlight, and hand-tracking. It looks at the possibilities of distance and connection between two people, whether geographical or metaphysical.

This year, I also finished three artworks: Your Sky Machine, Your Weather Machine, and Your Horizon Machine. They are interactive installations. With Your Weather Machine, I created a virtual skylight. It is a circular shape, which emphasizes that it is not a real window; it is not bound to a specific time or place. It frames a sensory projection of the sky, with clouds. The color and density of these are informed by real-world readings from photoresistors and a humidity sensor.

The idea behind it this is: China is 12 hours ahead of New Haven. Whenever the sun is rising up here, the sun is going down there. I want this machine to break the temporal and spatial scope, so I can see the same sky that my family is seeing at home. This is like SEED, in the way that it becomes a carrier of emotions; it is small and cute, like a little companion who empathizes with me. The sky and the sun give me similar feelings, but in contrast, they are so vast and grand that they can soothe away all my sorrows and frustrations. No matter where you are, we all see the same sun and the same sky. We all reside on the same Earth.