︎Speculative Relics︎Lauren Dubowski︎Speculative Relics︎Lauren Dubowski︎Speculative Relics︎Lauren Dubowski

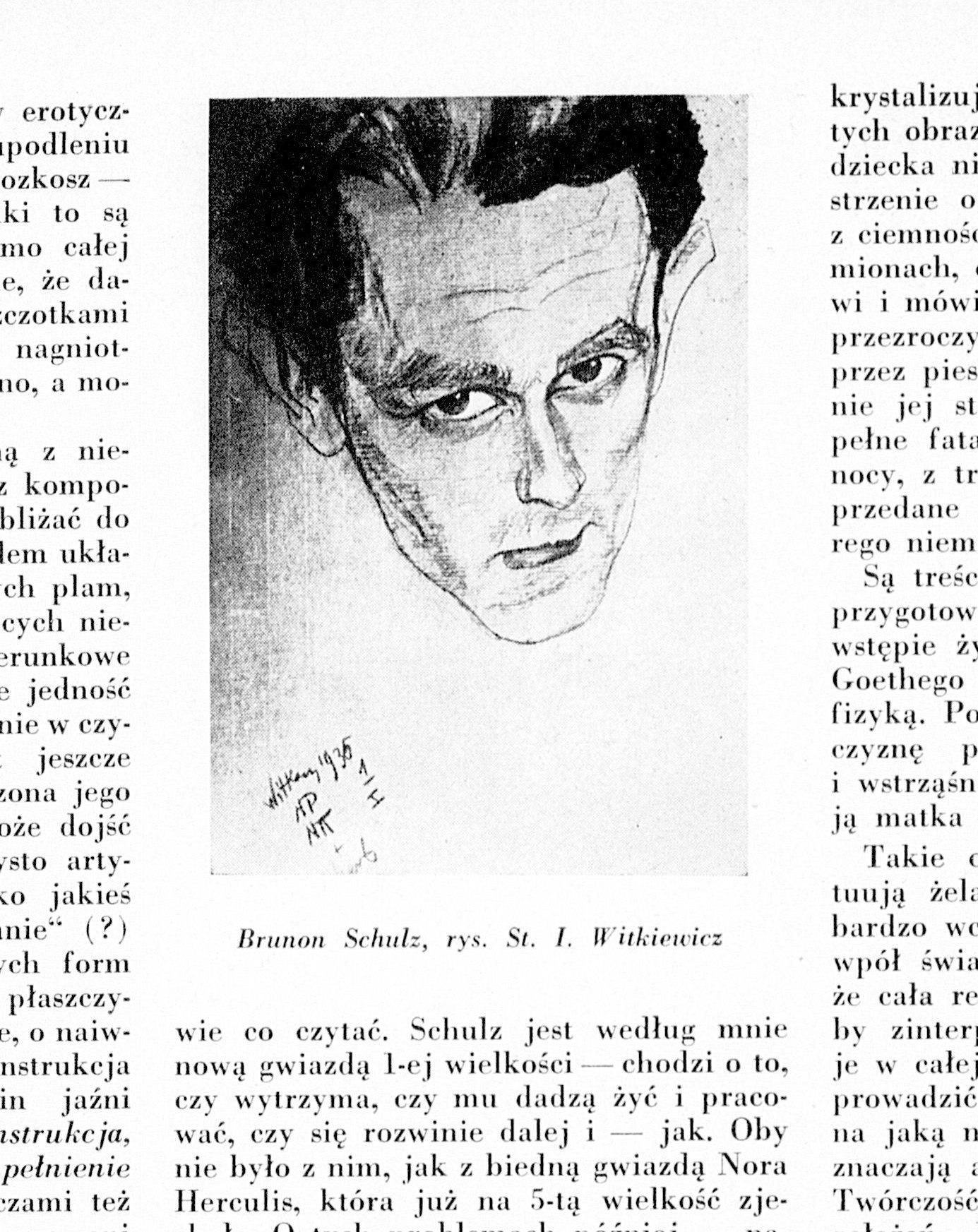

Drawing of Bruno Schulz by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz in Tygodnik Illustrowany, 1935.

From Biblioteka Narodowa, Poland.

Speculative Relics

What I’m Working On

Lauren Dubowski

I lived in a city that once stood in ruins.

If you visited me then, and you didn’t know, it might not be easy to tell at first. Warsaw is Poland’s bustling capital. Stepping out of Centralna train station, you’d see the looming, Soviet-era Palace of Culture and Science. Near the metro entrance, people might be selling flowers, used books, or smoky oscypek cheese from the mountains. Maybe we’d duck into the busy, underground maze of bakeries, shops, and hair salons. If we climbed up the stairs to explore downtown, I’d point out a few decorative, midcentury neon signs, a notable element of the urban landscape. You’d see local cafés, as well as pho shops—the city has for decades been home to a historic Vietnamese community—amid international chains, corporate headquarters, and hotels. If we hopped on a tram in the other direction, we’d pass by the stark new edifice of the Museum of Modern Art, or the giant, artificial palm tree created by the artist Joanna Rajkowska. If we got out and walked north, I’d show you the elegant, classical façade of the National Theatre and Opera. These are mere glimpses of the extensive, vibrant arts scene.

Reaching a district with narrower, winding streets, you might wonder at how spotless it seems, despite the name: Stare Miasto, the Old Town. That’s how I felt, too, nearly 20 years ago, as I was just getting to know the city I now consider my second home. Here, the colorful tenement houses surrounding the statue of a river mermaid, the city’s symbol, feel somehow hollow; the exterior of a church, angels sculpted into its heavy doors, has an unusually unadorned interior. If we stopped into the Muzeum Warszawy, you’d learn, in the depths of its sprawling collection, the source of this strange feeling. Eighty-five percent of the streets around you, along with much of Warsaw itself, was destroyed by Nazi Germany in World War II. Period photographs show an utterly decimated, unrecognizable landscape. Once the Stalinist Polish People’s Republic was established in 1945, some wanted to leave it that way, as a monument. But Poles who loved their capital, and former residents who longed to return, insisted on rebuilding it. Many joined in the effort themselves.

It was possible to reconstruct the district thanks to records, paintings, and remnants. If not 100% accurate, the result was impressive—by 1980, this marvel was hailed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I find it uncannily moving. While originally built over centuries, today’s Old Town is both real and false, faithful and flawed, healed and broken. I returned there regularly on my visits, which turned into years as I immersed myself in Polish culture and learned the language to fluency. I traced a forgotten branch of my family history, with roots in Eastern Poland—carried in my DNA and last name. Over time, I noticed increasingly how other areas of the city had clearly been revived in bits and pieces. Warsaw’s panoply of architectural styles can change door to door, or as your eye moves up one building. Some did survive the war intact—like in Praga, the neighborhood over the Wisła river, where I eventually moved. It’s known for its shrines to the Virgin Mary that twinkle from the courtyards of tenements, all in various states of repair.

But what about the parts of Warsaw, I often wondered, that could not be so easily recovered?︎But what about the parts of Warsaw, I often wondered, that could not be so easily recovered?︎

But what about the parts of Warsaw, I often wondered, that could not be so easily recovered? The Nazis burned libraries across Europe; in these and other wars around the world, past and present, the aim of oppression is not only to end a people, but to eliminate their culture, traditions, and language. In an online archive, I found my great-grandfather’s birth certificate; although he was Polish, it’s written in Russian, the language of the occupier in his region at that time. I discovered that his mother had been Jewish, but converted before marriage; mother and son left for the US together in 1923. In Poland, it’s impossible not to engage with Jewish history. There are traumatic stories, and joyful ones, so many the subject of care and commemoration—including by my friends and colleagues who celebrate Jewish contributions to Polish art, music, or literature. From a fascinating article Mikołaj Gliński wrote for Culture.pl, I learned the story of Mesjasz (The Messiah), a rumored lost novel by Bruno Schulz (1892–1942).

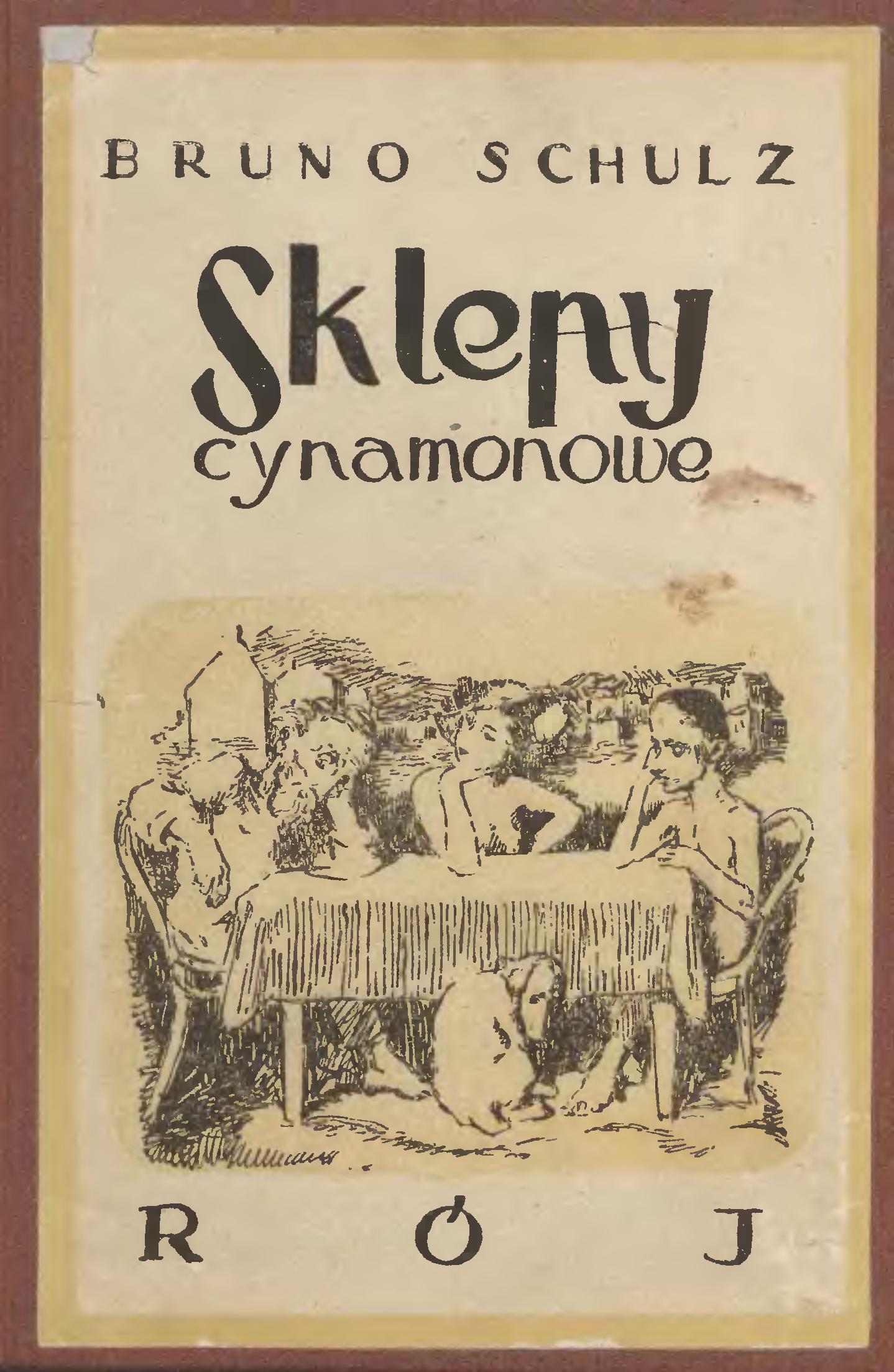

Schulz’s biography is as complex as his striking, often troubling tales, written in visceral prose, many accompanied by his own drawings. A self-taught artist, he experimented with cliché-verre, a darkroom technique where images made on glass are transferred to paper. Schulz’s 1934 collection, Sklepy Cynamonowe (Cinnamon Shops, or in Celina Wieniewska’s translation, The Street of Crocodiles), pulls the reader into a surreal, constantly shifting, and mystical vision of life in his hometown, Drohobych (then Drohobycz), in today’s Ukraine. Born to a Jewish family there, Schulz became a public school art teacher, and ultimately, an important figure in Polish modernist literature. After the USSR, and then Germany, invaded Poland, Schulz was in 1941 forced into the Nazi ghetto in Drohobych; just over a year later, he was shot in a revenge plot between two SS officers. Along with him, many of Schulz’s works were lost—including The Messiah, possibly his masterpiece.

Bruno Schulz’s cover drawing for his novel Sklepy Cynamonowe (Cinnamon Shops), 1934.

From Federacja Bibliotek Cyfrowych.

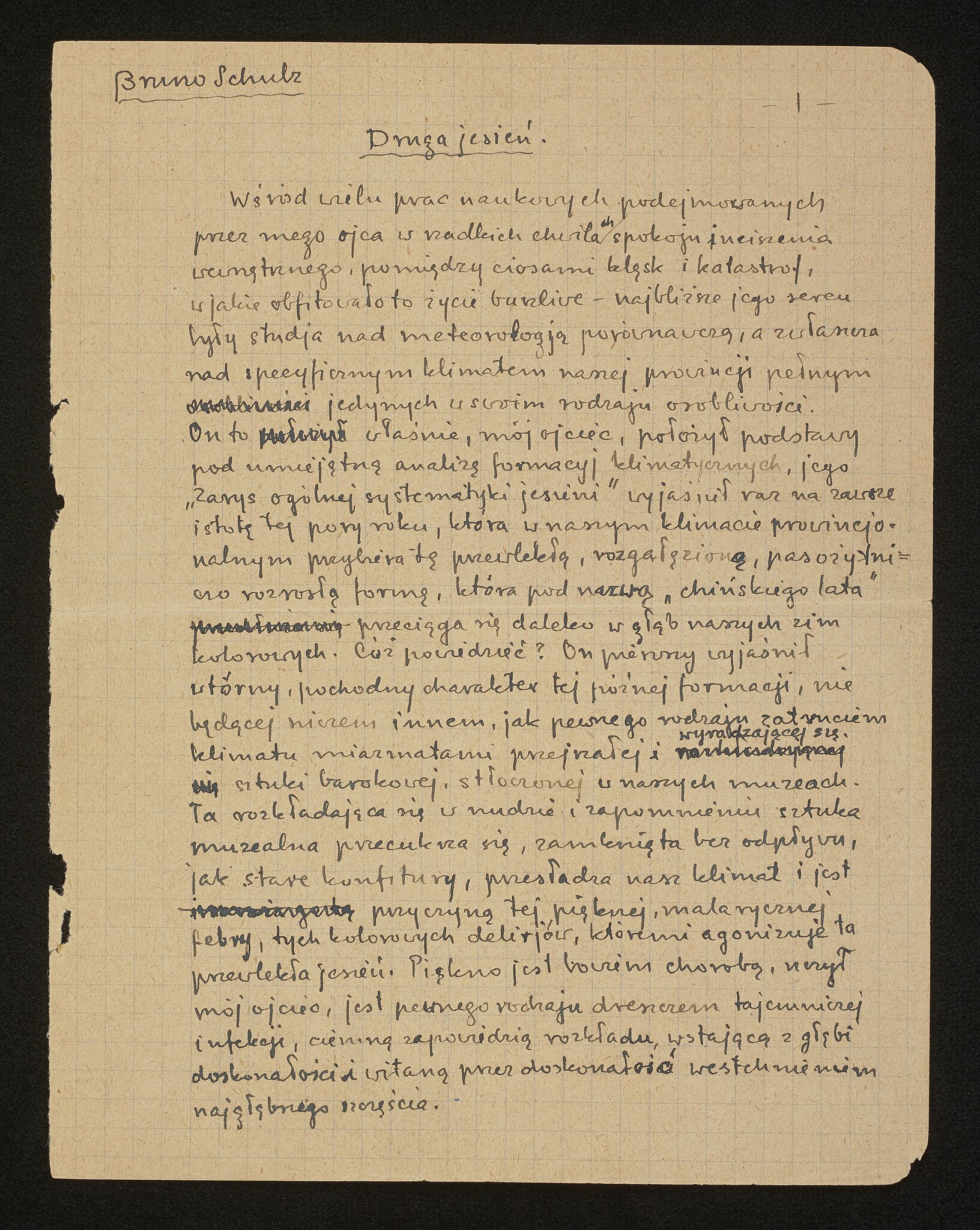

Schulz called the work-in-progress his “baby” in a letter that attests to both its significance and his writer’s block. However far along it was, it’s understood that he may have entrusted the manuscript, among other materials, to someone outside the ghetto. While in recent years a lost short story by Schulz, and a series of murals he painted, have resurfaced, the novel remains elusive and irresistibly so. There are clues: Artur Sandauer, a literary critic, professor, and Schulz’s childhood friend, claimed the author had once read him the novel’s first lines (my translation):

“ ‘You know,’ Mother told me, in the morning. “ ‘The Messiah has come. He’s in Sambor already.’ ”

Two years ago in The New Yorker, the writer Kathryn Schulz told, breathtakingly, of a family legend—her grandfather, a possible relative of Bruno’s, had been contacted by someone in Lviv, who was seeking a buyer for the legendary manuscript. The tale turned out to match an account related to Jerzy Ficowski, an earlier Polish poet-writer-ethnographer who devoted years of his life to searching for The Messiah; at one point, he even dug up a woman’s yard in search of clues.

In 2021, when I moved back to the US to join CCAM, I left behind many of the books I’d accumulated. But The Messiah, or rather, its story, came with me—at some point, I had succumbed, like others, to its mystery. One afternoon on campus, in the Bass Library, my mind drifted back to it. I began to wonder about other works like it, which only partly or possibly existed, and would probably never be found. How many bookshelves—like the ones around me, filled with Yale’s catalogued collections—would it take to hold the world’s lost literature? What evidence do we even have of these damaged, destroyed, or misplaced stories or books, poems, or dramas? I browsed a list of lost literary works on Wikipedia. Hundreds of entries encompass various languages, time periods, and forms. There are New Testament apocrypha, poems by Sappho or Ihara Saikaku, Shakespeare and Racine plays, a novel by Sylvia Plath, a pamphlet written by George Orwell. Aztec and Maya codices, most Middle Persian literature, and a Gilbert and Sullivan score share similar fates—if for different reasons. I was most drawn to the accounts of how certain works came to be lost. A hard drive of Terry Pratchett’s unfinished writing, I read, was run over by a steamroller, in accordance with his last will. Still: What about those not listed? Some literatures are only spoken, signed, or performed; others written in extinct or indecipherable languages. Some may have simply disappeared. Are those works gone forever? Does anyone remember?

Are those works gone forever? Does anyone remember?︎Are those works gone forever? Does anyone remember?︎

In the meantime, AI has transformed the larger conversation about writing, in all its forms. With a mix of excitement, fear, and skepticism, people everywhere from the media to art festivals and universities are discussing how large language models are changing our relationship to this until-now uniquely human practice. We have been writing, as far as we know, for at least 5,000 years. At the same time, AI image generators have opened up similar questions in the realm of visual art. These technologies have been used to recover lost cultural matter, or to challenge cultural norms. A program called Ithaca has helped to fill in damaged Greek inscriptions on ancient stone; Masakhane, a grassroots initiative, encourages the inclusion of African languages in research on natural language processing, and protects ones that are endangered. Joanna Zylinska’s 2021 photofilm, A Gift of the World (Oedipus on the Jetty), is a feminist, gender-fluid response to Chris Marker’s 1962 La Jetée, created in collaboration with AI language models and StyleGAN2. AI is being used to analyze and envision the rebuilding of war-torn cities in Syria and Ukraine, much faster than was possible for Warsaw. All of these approaches, however, rely on significant bodies of extant material. I wondered what an AI exploration of something irrevocably lost could bring—for Schulz’s Messiah, for example, it’s only possible to draw from what is known about it. What might AI bring to its tantalizing phenomenon?

The first page of Druga Jesień, or Second Autumn, the only surviving literary manuscript of Bruno Schulz. Held in the archive of the Polish journal Kamena. Archive of Jerzy Ficowski, Biblioteka Narodowa, Poland.

The first page of Druga Jesień, or Second Autumn, the only surviving literary manuscript of Bruno Schulz. Held in the archive of the Polish journal Kamena. Archive of Jerzy Ficowski, Biblioteka Narodowa, Poland.

I’ll never be able to actually create the shelves of lost works I saw in my mind, but AI can help me make something of them—which has launched this project, Speculative Relics. I’ve begun collaborating with ChatGPT to generate “lines” of The Messiah, creating an imaginary version of the text, in the state it could have been in if Schulz did pass it on for safekeeping. I’m asking the tool to draw inspiration from the stories, details, and scraps of letters I’m finding in my research. In one experiment, the narrator imparts these words, echoing the novel’s supposed start (my translation):

“But I knew that He—the Messiah—would not come through the front door. He would appear in the wardrobe, between the overcoats, among the mothballs and the dusty hats, or at the bottom of a drawer, hidden beneath a crumpled letter from years ago.”

I’ll also explore what Schulz’s manuscript might have looked or felt like—again, if it existed, and based on both research and speculation, in dialogue with AI. Could he have sketched on its pages, tucked them into an envelope, or tied them with string? To muse on these possibilities, I’ve started working with image generators like DALL-E and Midjourney. Moving forward, I’ll use outcomes from the written and visual processes to create, using paper and ink, a real-world, physical model “of” The Messiah—one you can hold in your hands.

While the practice of forgery runs through literary and art history, that’s not my goal. I want to create a tactile symbol of the reputed work that is clearly false, and while informed, undeniably imperfect—something between a mathematical limit and a shot in the dark. As if Warsaw’s Old Town were somehow rebuilt from missing records. I hope my efforts will spark interest in works like this, and their authors, and encourage conversation around important questions of culture, ethics, and authorship as AI increasingly permeates the world around us. Perhaps in the future, I’ll invite artists who speak other languages, and know other literatures, to help create models of other lost works; together, we could build something like those impossible shelves. As an early exploration, I invited Vignesh Hari Krishnan—a graduate of Yale School of Architecture, a former CCAM Studio Fellow, and a native speaker of Tamil—to prompt ChatGPT on a work of his choice. He selected the missing books of the Tirukkural, or Kural (Sacred Couplets) by the Indian poet-philosopher Thiruvalluvar, also known as Valluvar. Written somewhere between 2,000 and 2,500 years ago, many details about their author, too, are obscured.

I imagine that I could also extend this process to generate similar iterations of legendary objects—from buried treasure never found, to items forever lost at sea. With each day, we hurtle farther and faster into a more and more technologically mediated future. We stand to lose as much as we’ll create and discover. With these speculative relics, I’d hope to keep some placeholder there for these more delicate outcomes of human creativity, which live on only in our stories and memories, inaccessible to code, clicks, and screens.