︎The Tensegrity Principle︎Eleanor Bauer in conversation with Molleen Theodore︎The Tensegrity Principle︎Eleanor Bauer in conversation with Molleen Theodore︎The Tensegrity Principle︎Eleanor Bauer in conversation with Molleen Theodore

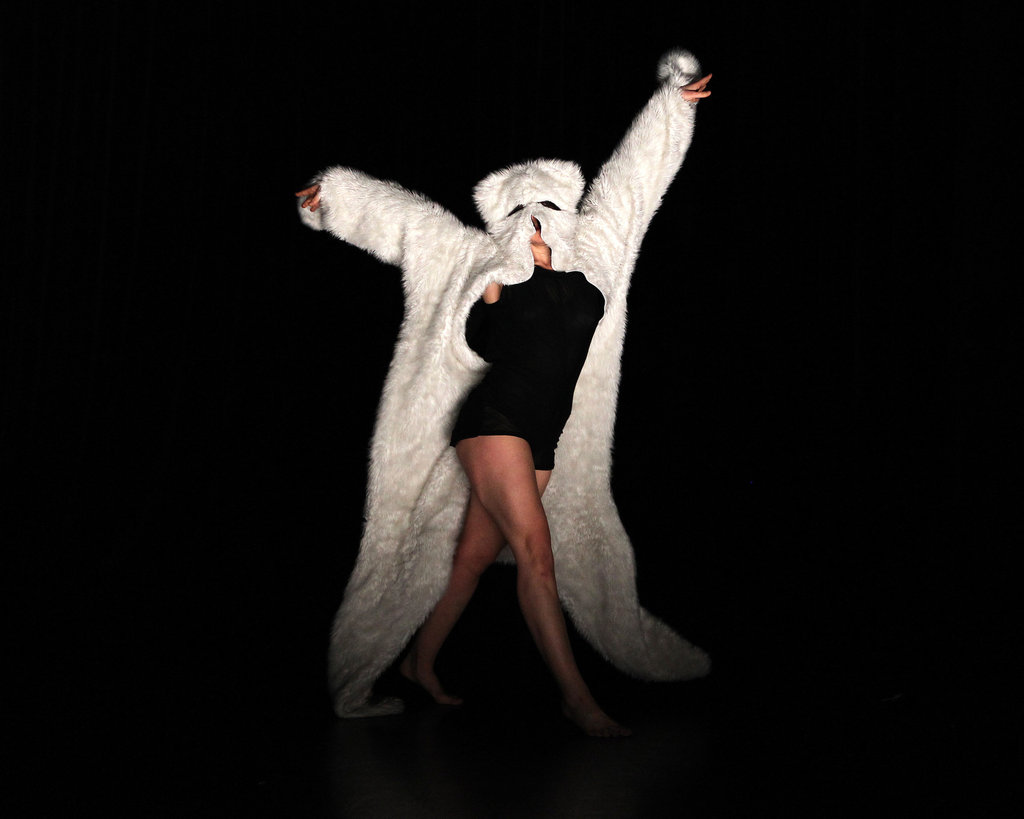

Eleanor Bauer in her performance piece “(Big Girls Do Big Things)” at New York Live Arts, part of Performa 11 biennial. Credit: Chang W. Lee/The New York Times. Image from The New York Times.

The Tensegrity Principle

Eleanor Bauer in conversation with Molleen Theodore

Eleanor Bauer in conversation with Molleen Theodore

This past spring, the Yale University Art Gallery presented Matthew Barney’s most recent exhibition, Redoubt. The expansive show was comprised of sculptures, drawings, engravings, and a feature-length film, creating a new world composed of layers upon layers of myths. Barney’s dense, thick language plays out through a story loosely adapted on Diana, goddess of the hunt, and her foil Acteon. The film is composed of six “hunts,” and was shot entirely in Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountain range, bringing nature front and center to both story and production.

True to the original myth, Diana’s tale includes two nymphs, and in Redoubt, they appear as the Tracking Virgin and the Calling Virgin. The latter is played by Eleanor Bauer, a dancer who also lent her choreography experience to the project. Bauer’s work deeply emphasized the animalistic and primal qualities of Barney’s vision; when Dana Karwas, the Director of CCAM, invited her to try out the motion capture studio, Bauer connected at once to the technological possibilities of image, movement, and intuition.

We invited Bauer and Molleen Theodore from Yale University Art Gallery to discuss the processes behind Bauer’s work. She is an artist whose experience as a performer and choreographer involves interdisciplinary research into writing, music, visual arts, and film. She has collaborated or performed with, among others, choreographers Xavier Le Roy, Boris Charmatz, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker/Rosas, Trisha Brown, David Zambrano, Mette Ingvartsen, and Veli Lehtovaara; musicians Chris Peck, Yung Lean, and The Knife; visual artist Every Ocean Hughes/Emily Roysdon; and filmmaker Mia Engberg. With Barney, she performed in River of Fundament, and both choreographed and performed in Drawing Restraint 24 and Redoubt. She is currently a PhD candidate at the Stockholm University of the Arts, where she is leaning into the etymology of choreography as the relation between khoreia (dancing together) and graphia (writing) in her research on language and movement. (For more information on her work, visit: eleanorbauer.info).

Theodore is Associate Curator of Programs at the Yale University Art Gallery where she develops and oversees myriad public programs. She collaborates across the museum, the university, and the community, developing partnerships; and she leads the student Program Advisory Committee. Theodore has supervised students in curating exhibitions, including Many Things Placed Here and There: The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery and Jazz Lives: The Photographs of Lee Friedlander and Milt Hinton. She holds a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center with a focus on the art of the 1960s and 1970s, and she is a 2017 graduate of the Getty NextGen program.

This is their second public conversation on the subject: their first was in April, soon after Barney—Yale ’89—received national acclaim for the show.

Molleen Theodore: Let’s begin by talking about your performance in Redoubt.

Eleanor Bauer: There’s a lot of counterweight stuff happening: a tensegrity principle. For example, it shows Laura and I leaning away from each other in deep snow as we’re walking up the hill. The idea is a triangulation principle of support, either leaning away, or towards. There is a scene by the campfire at night, which is a tripod action, which is just a simple choreographic rule of only being allowed to be on three limbs at once, but trying to always be on three. That is why we are low on the ground, locking gaze with each other. For the characters it’s a game, and how they train, and also how they relate to each other.

MT: Are there other instances in the film where you impose limitations for yourself?

EB: I think the tripod dance at the campfire is the only choreography that is generated by improvising around a rule. We actually transposed the tensegrity dance we do up the hill, which is a set phrase, to the bathing scene in the hot spring that feeds into the river. We do that same choreography, but all the physics of our counterweight are completely changed by the water. It is almost unrecognizable, but it’s the same choreography. The limitation in that case is the environment; that also determined what was possible. All the planning and thinking we had done ahead of time was twenty percent of what actually happened. Eighty percent was responding to the conditions as a limitation. This was especially true for the scene where I am climbing a giant burnt tree, which as a limitation was so unpredictable.

MT: When you visited our motion capture studio, and put the motion capture suit on, you enacted animal motions from the film.

EB: Yes, from Hunt Six. That is when we are really closing in on the animal at the end—that is when it gets the most… hmmm. What is the opposite of anthropomorphic? Animamorphic? I think that the choreography of the film really starts from a position of human hunting or stalking, which relates to animal awareness in the wild: listening, seeing, stillness, great subtlety, a hyper-attentiveness to the environment. As the film progresses, the physical movements of the body get more and more developed and expressed. Hunt Six is the most dance-y. It relates a little bit back to what Sandra Lamouche does in the film. When we collaborated with her, we were using the vocabulary of her hoop dance, which already had animals in it, and created other animal forms together which were then included in both her dance and mine/Laura’s in Hunt Six. We all do this eagle pose that became a refrain, for example, with the arms spread outward and the fingertips downward, like an umbrella, a lofty pose with arms outstretched.

︎For me, forms are just containers for experience.

It’s funny: recently I was doing a Tai Chi Chi Gong class. One of the movements was almost exactly like the crouching eagle pose that we do in Redoubt. I was like, Oh dang, I guess it is intuitive. Everyone who wants to make an eagle shape, probably makes it like this. It’s memetic. In Redoubt, we do animals and it is a little bit silly sometimes, but from a dancer or choreographer’s point of view, we work up to it in an acceptable way by imbuing it with a certain attention, so that it’s more about the “how” than the “what.” And also: just honoring the simplicity of the formal container. For me, forms are just containers for experience. There are a lot of older, or premodern, forms or even story ballets where you embody an animal in order to invite a certain consciousness; whatever that animal sees, feels, or narrates is something you can embody, or be a medium for through a certain form—even though you are always going to be human. There is almost a ceremonial aspect to that dance in Hunt Six before we have this climactic wolf kill.

MT: That goes back to your idea about the dancer being a medium who expresses the dance.

EB: Many acting schools and methods probably feel the same way. In any artistic experience, there is the potential of feeling that something is happening through you, rather than you willing an expression. The subject is a medium that ciphers and filters experience as stuff happens through this structured thing called a subject, or subjectivity. This constructed idea of self, or conduit idea of self, is really strong for me in dancing. It’s really tactile and tangible, to the point that I feel almost changed by the dances I do, more than that I am doing something to them. There is a certain active-receptive exchange, or a fundamentally receptive attitude towards the dance that I am interested in fostering.

It’s in the same way that language comes from the outside. The linguist Vyvyan Evans wrote a book called “The Language Myth,” which very carefully and academically refutes Chomsky and Pinker’s popularized idea that language is natural, instinctual, or structured neurologically in a universal way. He points out—using examples from around the world—how absolutely cultural and outside-in language is developed and built up, through centuries and lifetimes of experience and practice. I feel the same way about movement. There is something common about most human movement—we stand up straight on two feet, we walk, crawl, crouch, sit, stand. These are more or less intuitive ergonomic functions, but they could have also happened in another way. Certain cultures use their feet way more articulately than we do, like planting rice with bare feet, instead of hands. All these ideas about the visual dominance of human perception in western civilization are, in a way, cultured lore. Amazonians who can’t see through the thick vegetation hunt with their ears. So: there is no essence that I am expressing, when I am dancing. I am expressing what I have been cultured by, and that can also include receptivity to immediate surroundings, or the plasticity and changeability of that instrument called my body that can invite stuff in, and express it.

MT: How does that change if you are the choreographer, or if you are following someone else’s directions?

EB: As a choreographer, I have a similar humility to the situation, but my job is to give it structure—to design a container that satisfies the demands of the situation, and in which dance can thrive, or through which dance can pass. Dancers are the conduit and the enactments of that thing, and sometimes it is me who is choreographing and dancing. Often the process is very collaborative with dancers. Some choreographers give a certain idea, and the dancers mostly figure out what the shape, container, or structure is; other choreographers have a very clear structure, or superstructure, and we all make up our own movements though or within it. It’s also typical that a choreographer doesn’t know what they want to see until they see it: the dancers are running around, to make the choreographer’s dreams come true without knowing what they are until Oh that thing, do that, yeah that’s it! There are many ways this can unfold, some more confusing and some more transparent than others.

My mom is a ceramicist, and my dad is an architect. This might be an influence! My dad makes containers for living, my mom makes containers for eating. There is a certain service, or function, or humility to that design which is not just about being a starchitect or being an inventor of a cool form. It is about serving a purpose. So: choreography for me is really a relationship to the place, the idea, the budget, the schedule, the people. Collaboration is really important. When I make my own pieces, I will have arrived at a dance-related problem, like: Oh, wow, how strange. Why is geometry so strong in social dances? Huh! And that opens up a whole contemplation on physics and society. I’ll get going, and maybe some other medium or field of expertise will become implicated in my research. The choreographic container will be inspired by things outside of dance, but then it will always come back through dance. Strong interdisciplinary reflection has always been a way for me to find structures that are relevant for the thing that I am experiencing or contemplating. Transposing or grafting structures or ideas between media.

MT: Speaking about different media, can you talk a little bit about the relationship of choreography to cinema, and the language of recording as it relates to Redoubt ?

EB: This was a learning curve for me, because I’d only done stuff like music videos before collaborating with Matthew. I had never really done a feature duration film. I am happy with how it went, and I knew going in that editing would be so important. I knew that we were going to create more material than we needed and that the huge structuring force of the choreography was going to be in post, by the editor Katie McQuerrey. The work really shone after she got her hands on it.

In dance, there is so much rehearsal on the front end, during which you imagine that a live performance is the product, the thing people are going to witness, that is then going to be called the art framed on the stage. With this film, even though we rehearsed and prepared, it was impossible to experience the locations and perfect the movement in this very influential environment beforehand. Once we were on location, the camera was often rolling from the start. You can’t really have a rehearsal process on site, not only because it costs so much time and money to get everyone together, but also because of things like continuity. During the production of Redoubt, I was so insecure of being filmed on the first cut of something that I’d never done in that place—you could only do it once, because afterwards the snow would be messed up, or I would be covered in ash the second time I would climb that tree. All these practical limitations forced a lot of improvisation and vulnerability into the situation.

MT: How do you record something when you are creating it?

EB: I have used video in the past as a quick capture, like a mnemonic device, but it is actually really rare that we need it. Once I get into the space standing next to the people, a three-dimensional, even acoustic memory comes back. It’s not the view from the camera where the memory lives, it is the view from inside of the piece that usually that comes back over time.

For documenting, I have used a lot of diagrams and sketches. For the choreographic process itself, I work a lot with language-based scores— where the limitation of the poetics is the thing that holds—so that the interpretation can always be different. That’s a productive difference I am interested in: if the score is three lines of a very poetic paradox, returning to that poetic paradox each time is where the ongoing work of dancing lives and performs. Maybe my body is changing, and maybe my practice is evolving, and it looks different every time, but it has a certain number of limitations that are consistent. The idea of choreography as a dynamic system that evolves through several iterations has become a thing for me in recent years. It also allows something other than imitation to be the driving force of what we are considering as the form or the choreography. Which also leads to more diverse kinds of bodies being part of the work.

But it is not to say that language is the only way to do that. I am interested in other ways too, but lately it has been language. People like the dancer Deborah Hay have been inspiring for that. She works with paradoxes and riddles a lot, so the choreography is often a written score that one could read on a page. There is a whole practice behind it, of how to interpret that choreography, which also defines the work, but the “writing” as text is a huge part of the formula. That's something I have been going into lately, and now I am looking at what other traces can be useful. That’s what I realized when I had visited the motion capture studio at Yale during the Redoubt visit. It clicked afterwards how interesting this technology is as a kind of limited cipher, model, diagram, or trace of a dance that is non-linguistic, and also not two-dimensional, because dance choreography in writing or in diagrams has historically always been two-dimensional.

All these ideas about the visual dominance of human perception are, in a way, cultured lore.

There are some exceptions with technology, such as Synchronous Objects which was a collaboration between The Forsythe Company and Ohio State University, wherein they took William Forsythe’s piece One Flat Thing, reproduced and modeled it in all these different ways using digital technologies and platforms. There have been some interesting experiments since computers got more involved in the studio in the past ten years or so. Typically, the word “choreography” has referred to mostly diagrammatic attempts on paper, a sort of tracing, or embodied memory of the dance. Moving into 3D is an interesting new potential for me to think about what trace to reinterpret and revisit. Especially the more abstract ones, like the point cloud where you don't have an animate human. It isn’t about an empathic, skin-faster-than-the-mind automatic mirror neuron reflex of imitation; there is something else, in the way that a poem or language would be really something else other than the dance experience, and allow a reinterpretation to proliferate new versions. Using motion capture also presents this opportunity for me. Because it is not the whole thing. I can’t just pick it up with my body and my visual/audio skills and tactile kinetic skills. But what it does capture is the kinetics—moving points have kinetics in them. You have a feeling for movement when you’re watching this point cloud morphing around space. So: there is something that triggers the movement empathy or response, but it is not a totally anthropomorphic one—maybe it is digitamorphic. That gets interesting, because then you are like the human in the machine, because well: we’re all cyborgs anyway! The human-machine relation can be very juicy and sensual through something that moves you.

MT: Are there any visual artists who inspire you?

EB: There are some things Agnes Martin has written that are epic. I just bought a nice book of Hilma af Klint’s sketches because of recent conversations with other dancers about the relationship between the spiritual and the physical, as well as conversations with Matthew about her scoring—she would “rehearse” her paintings in her drawings, which is an old-school thing in painting, but it feels almost choreographic in her case, the way that she was inventing these forms. It wasn’t mimetic and it wasn’t representational of something she was seeing. The sketches were like a figuring-out of something immaterial, or something moving through her as she was trying to find the right form. She had a whole language also, of words and vocabulary, behind her work.

MT: Yes, her work does seem pretty graphic to me.

EB: Well actually, Matthew is in some ways. When I met him, I didn’t recognize him. We hit it off, talking about things like both growing up in the Rocky Mountains. He looked at me and thought I was strong, and could do this thing he had been looking for the right person to do in River of Fundament, which was to lift a small man over my head. I fell into this situation of working with somebody who I had actually admired before, as an artist, for his layering of different meanings and mythologies. There’s a kind of maximalism in his work that I relate to. I’ve always felt like I want to see how much I can pack into a performance and still let it get away with being one piece. I feel like I am making a million pieces when I am making a piece. Or when I am dancing, I feel like my body is a conduit for so many experiences, affects, images, and sensations. When I choreograph, I think of physical sophistication and a saturation of experience, and that’s what I want to share with an audience.

As a dancer, I want to carry that into the choreographic, so that I can communicate that richness, density, and saturation of meaning, or of experience. Choreography can often be more about controlling movement, designing it, and capturing it in your preferred image than it is about enabling a proliferation of different, or of a thousand different possible experiences. I prefer the latter. Dance is super connotative and not denotative; it is very suggestive of meaning, but it doesn’t ever really mean one thing, with the exception of, say, pantomime in story ballets. It’s very prolific in terms of meaning potentials. So: Matthew’s work is inspiring for me, because it is unapologetic in its density of meaning. It’s not one story or one representation in each scene or image. Especially his films. When I first saw the whole Cremaster Cycle at the Guggenheim in the early aughts, it felt like dance to me.

MT: How do you teach that?

EB: There is something my friend and mentor Chrysa Parkinson says: “Include, don’t control.” This has to do with physical practice, information from others, or things that are showing up while you are dancing. Now it is a tagline for me. It runs through all kinds of practices, creative or performative. That’s the shortest summary of a simple rule that leads to complex outcomes. When I teach physical practices, I encourage it. Awareness is open and inclusive, and concentration is focal. I work a lot with the awareness of attention being malleable, just noticing that the senses can bleed or spill or go 3D or focus and narrow, align; there is all this movement and oscillation between global and focal attention, which a thing Pauline Oliveros hones in her Deep Listening philosophy and practices. Expansive awareness and inclusion is what I am swimming in, and enjoying. Other people have very different attention forms that they tend towards. So, in mentoring or in teaching, especially when it comes with art making or authorship, learning to use attention as a malleable substance—as well as noticing what your attention does, what its tendencies are—is authorship for me. What shapes you as an author is very much where your attention goes. Making a piece can also be like asking your audience to turn its attention towards what you’re turning your attention towards. So studying your own attention is getting to know the sort of proto-medium of your work as an artist. Attention as a medium is my thing!

Dana Karwas: Was there an initial moment when you realized language and poetry were important for you?

EB: When I first started making pieces, I was encouraged to choreograph stuff in high school. From the beginning, it included language. I am a very verbal person, a real talker! So yeah: Language, articulation… I like the pleasure of finding the right word-containers for a felt-sense experience. The pleasure, or struggle, of this is something I have been working with unconsciously for years. When it happened upon me to apply for a PhD, I sort of recognized it more explicitly as choreographic. So, while I had worked with different media for a long time, and even it got into songwriting and monologue writing, language was always present. I never really considered myself a choreographer. I always felt really uncomfortable with that title, because I thought of it as a very formal and controlling practice, because that’s typically what it has been in colonial western modernity.

I have a weird relationship to expression and entertainment that, for some reason or another, I haven’t shaken. Or: why would I shake it? Dance has never been abstract to me. Choreography has generally been conceived of as an abstractor, historically, an abstractive device. When I was applying for this PhD in choreography, I really started reflecting on the etymology versus ontology of “choreography”: recognizing this consistency of language sense-making with dance sense-making, how they differ so much, and where they can possibly align. Language is generally referential as a system; we talk about stuff. In western philosophy and linguistics, we speak about a separation or difference between the signifier and the signified. And there’s this whole concatenation of binaries that unfold from that assumption, and it is mostly connected with written history. Because in oral traditions and oral cultures—Walter Ong writes about this a lot, so does Édouard Glissant—there is the voice, and the voice is vibrating from inside your body, and it is in a life-world with all the verbal and ritualistic agreements; and the live presence of voice is not about a signifier or signified, it is now, wherein the speaker, the spoken, and the hearer, constitute one whole. Everything is now.

In this way, dancing and oral culture have a lot in common—in the social temporality. In the group, in this moment, in our bodies, in the vibration of your voice that this meaning or this message is happening, it is an event, it is not a trace that exists outside of some other realities. There is this supposition which has evolved with writing, that language is referential, and for me, dance is not referential. Dance is very oral: the sense-making is here now, it is social, oscillatory, vibrating, it is moving through bodies. It’s meaning isn’t to be captured, and there is no dictionary about it.

I was looking at how movement is more connotative than language. You could say it is more denotative. And of course: all these things are not true, you can always say the opposite is true. What led me to poetry was Aha! Poetry is a situation in which language can do something else! Putting this word next to this word; the compositional aspect of it; the poetics, the poetkai teknai; words will hit up against each other and vibrate and make new meanings. There are opportunities with poetry that bridge the differences between writing-thinking, and dancing-thinking.

Also: “Choreography” is a word that was invented in 1700. It hasn’t been around forever. It means dancing-together-writing or “the writing of the dancing together.” In colonial western modernity, writing is a very solitary act: mostly it is a thing you do alone, your eyes to the page with your hand, an introspective or reflective work. Dancing is generally more social and externally focused. I am not the only one who thinks it is totally boring to go to the studio alone as a dancer. So, there are general tendencies of the global, the focal, the social, the solitary, the foreverness of the trace of writing and the need to reenact, practice, and reactivate the dancing; this suggests a lot of tensions or oppositions in the word choreography. Poetry is just one bridge between those two extremes.

It carries in it the trace of the oral and the written, these tensions. The first writing tools were very limited. It would take forever to etch out in stone or hammer into a leather. You had to choose your few words, because it is going to take a long time to get them down. Unlike in the oral tradition of rhapsodes—loquacious and flowery in their speech—there was a lot of rhythm and rhyme and song in order to remember them. But in writing, Alexander the Great would become Alex. It’s an intense condensation of writing against a superlative excess of orality. I feel these tensions are active in poetry still today. We still think of poetry as something with a lot of line breaks or that it is short—that is stereotyping, of course, there are other traditions. I feel that there is a lot of potential to look at different traditions in poetry or writing for ideas of how to make words move, or how to find adequate linguistic expression for what is happening in dance. Towards new ideas about what choreography could mean.