︎Three Proposals︎Jake Gagne and Molleen Theodore︎Three Proposals︎Jake Gagne and Molleen Theodore︎Three Proposals︎Jake Gagne and Molleen Theodore

Three Proposals

Jake Gagne and Molleen Theodore Investigate Public Engagement in a Pandemic

Jake Gagne and Molleen Theodore Investigate Public Engagement in a Pandemic

As museum workers in the field of public programming, we have been wondering what visitor engagement could look like in a pandemic. How do we facilitate conversation and thoughtful encounters with original works of art if we can’t safely gather together? How do we hear new voices, listen to different perspectives, and witness the exchange of ideas and experiences? How can we continue to open ourselves to creating new communities and sharing our collections and resources when the Yale University Art Gallery is closed?

This past year has required everyone to think differently about how we work, eat, shop, and play. It has also inspired us to rethink our approach to public programs, and reconceive how we imagine common space and acts of exchange, whether physical or intellectual. Following a speculative dialogue with CCAM director Dana Karwas about how to resituate the museum experience out-of-doors, we developed concepts for site-specific programming and opened a call for student participation. With Karwas, we selected three Yale architecture students—Noa Hines, Nikita Klimenko, and Timothy Wong—and invited them to visualize the three prompts. “The idea is to use what you read and/or hear from these words to generate future images,” Karwas wrote in her directive. “The approach should be what you imagine and feel. You as students are opening up a spatial optimism to allow the ideas to escape the text!”

All of the concepts are based in New Haven. The first suggests transforming the museum into a sculpture parade through the streets. The second transforms the city’s landscape and airwaves into media for broadcasting art. The third activates the waterways as a moveable gallery space for artist commissions.

We invite you to spend some time with the visual renderings created by our collaborators, all of them richly detailed works of art in themselves. These images are more than just illustrations of our ideas. They draw out subtexts, offer critiques, and most of all, argue for new ways of gathering and learning together.

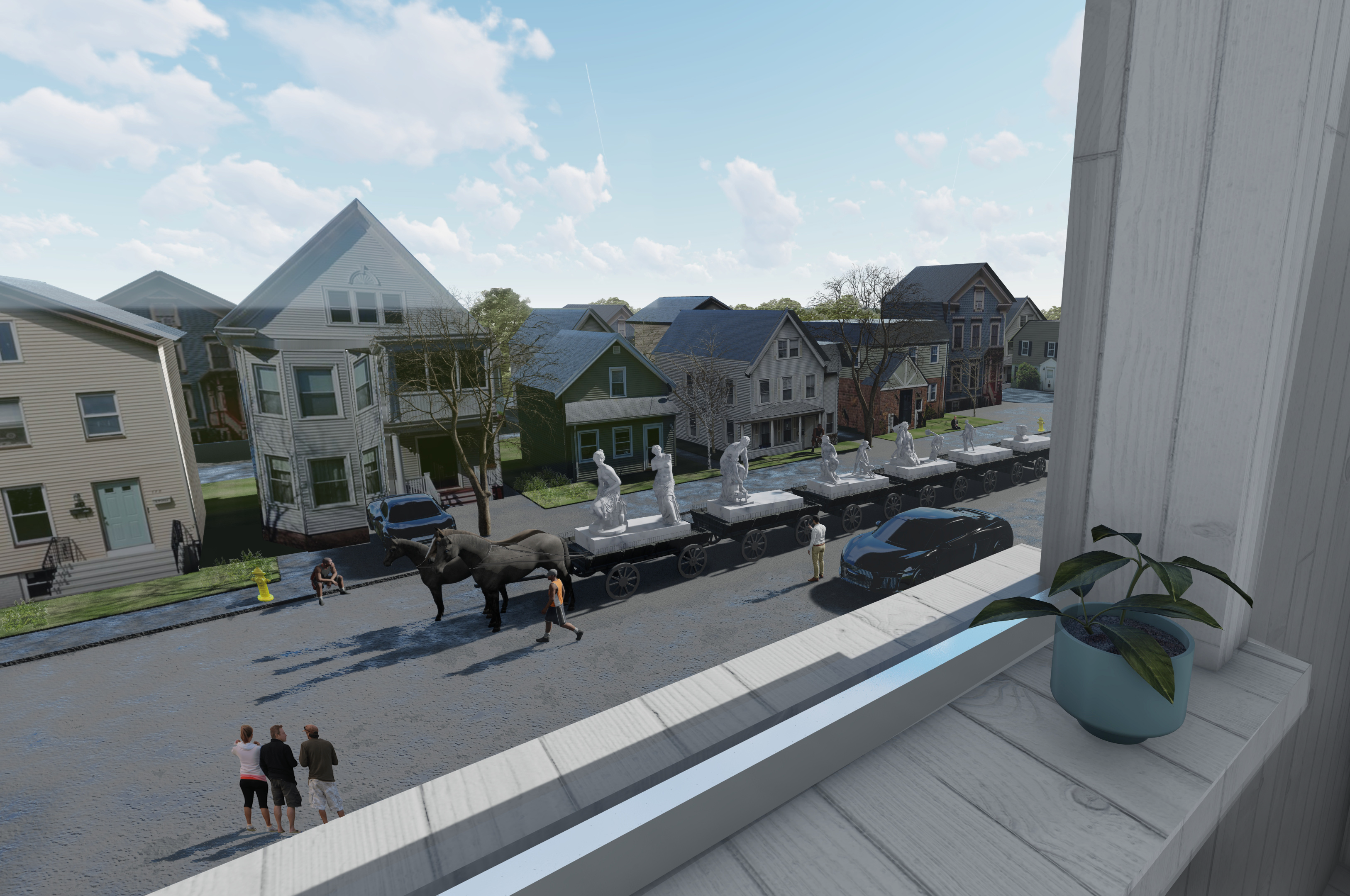

Sculpture Parade

Inspired by drive-by birthday parties and graduation ceremonies, and with a nod towards public art spectacles like Francis Alÿs’ 2002 Public Art Fund project, The Modern Procession, the Sculpture Parade brings art into the open air. The route begins outside the Gallery at Chapel and York Streets, heads west through Westville, northeast through Beaver Hills and Dixwell, and back to the Gallery. The parade includes several floats with artworks chosen by a team of Yale curators, students, and community members. New Haveners will be invited to view the parade from their homes, sidewalks, parked cars, or anywhere they can watch safely. A map of the parade path will be shared in advance, along with information about the work on show, and questions to spur conversation and reflection. (Three-dimensional printed replicas may be substituted for any work too fragile to travel outside.)

Hines observes: “The pandemic seemed to completely shutter the art world, and I saw a slow scramble to devise ways to display art without gallery walls.” During a period of social upheaval, she asks, “How do we continue that momentum of innovation so that exhibitions not only expand their audiences, but also present art in a newly-immersive format that supports physical and digital work? What do future exhibitions look like in a post-COVID world? What does attending an exhibition opening look like, when four walls are expanded across the globe?”

Image by Nikita Klimenko, 2020.

Neighbors,

Timothy Wong, 2020.

Image by

Noa Hines, 2020.

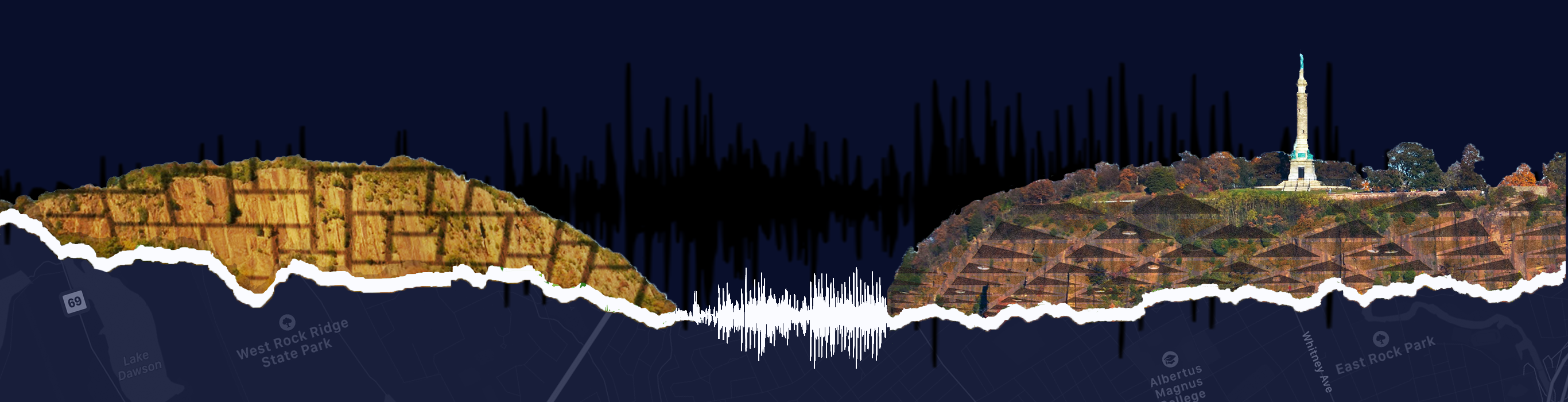

Art Rocks:

Projection and Sound

Working on these renderings prompted Klimenko to consider pragmatic physical details: “How dark does it get before you see projections on the rocks? How do you mount marble sculptures on a cart, and what material is the platform made of? How do you keep structures stable in the water?” Though the planning process revealed some of the issues associated with implementing a new technology, the project “also manifests the inherent human ingenuity and hope for collective, creative, communal solutions to global challenges.”

Windows,

Timothy Wong, 2020.

Images by Nikita Klimenko, 2020.

Image by

Noa Hines, 2020.

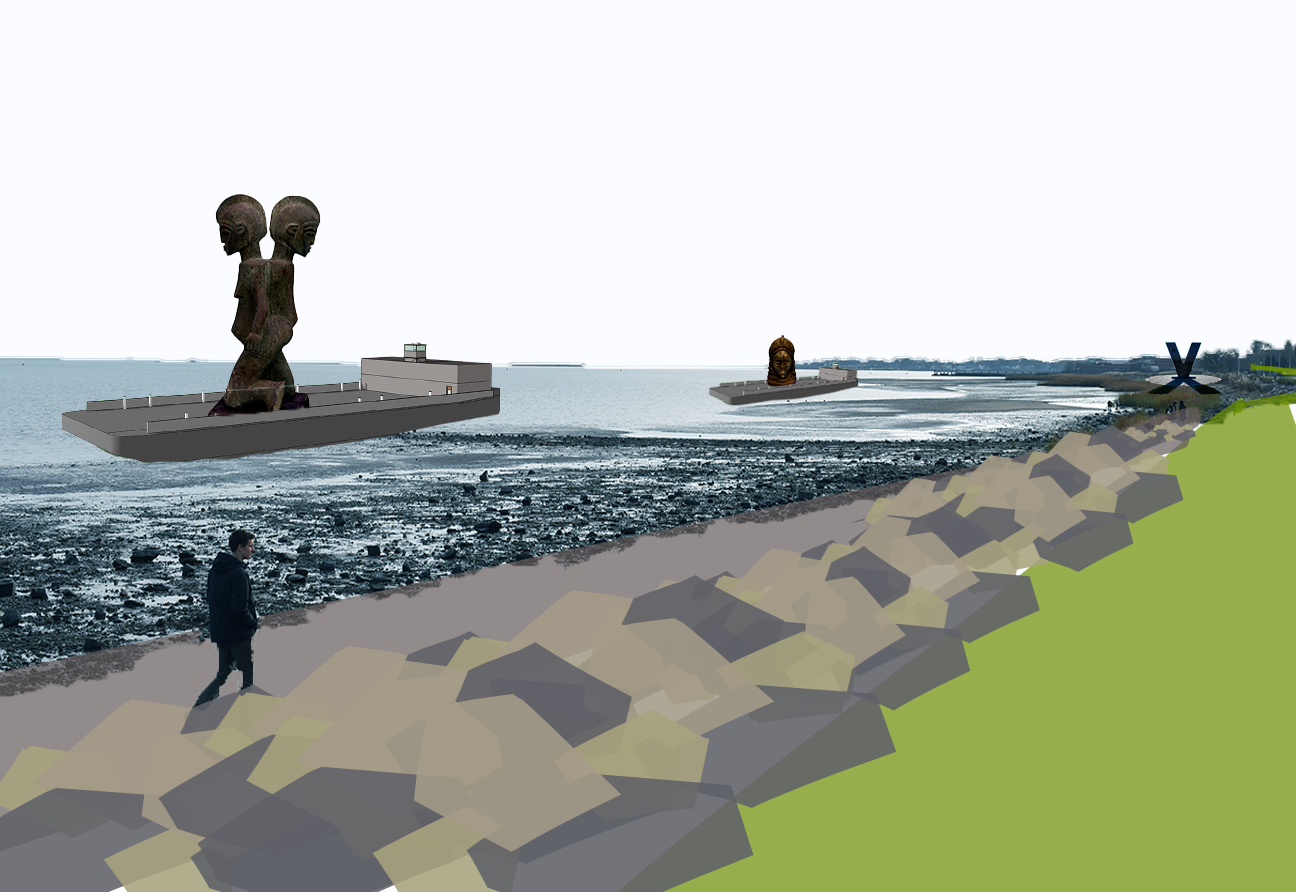

Art on the New Haven Harbor

This attempts to capture something of the experience of visiting the Gallery, but transplanted to the city’s waterfronts. It looks to visionary projects like Robert Smithson’s 1970 work, Floating Island (posthumously realized in 2005), where the artist imagined a barge landscaped with the flora of New York’s Central Park circumnavigating the island of Manhattan. A curatorial team will select an artist to create an installation that inspires wonder, curiosity, and imagination; brings people outside; and makes New Haveners more aware of the waterways and natural resources that connect the city. Mounted on a fully electric barge, the project will travel the perimeter of the harbor, including Long Wharf, Lighthouse Point Park, East Shore Park, and up and down New Haven’s portion of the Quinnipiac River.

Throughout this project, Wong was fascinated by “the intersection between the everyday with the fantastical.” He notes: “Remaining almost banal, these moments of weirdness start to reframe how we experience our everyday spaces. Through this, maybe we could find the fantastical in what we characterized as ordinary as well.”

Image by Noa Hines, 2020.

Image by Nikita Klimenko, 2020.

Picnics, Timothy Wong, 2020.

Although these proposals are speculative and fanciful, they are also useful: They allow us to ask questions about the work we do in “normal times” and to think towards new possibilities during the pandemic and for the post-pandemic world. In a moment of existential uncertainty, it seems productive to reflect on what public programs can and cannot do. Perhaps we can’t parade ancient Roman statuary through New Haven on a horse-drawn cart (for all sorts of reasons), but can we push beyond the physical walls of the museum building and find new ways to show up for our city? We may not have the budget or technology to project monumental images onto East Rock, or put art on a barge, but can we use our collective creativity and resources to foster a similar spirit of encounter, surprise, and curiosity? Looking ahead, we believe arts programming can continue to enliven our social, spiritual, and political imaginations, and bring people together as a community.