︎Bilateral Symmetry︎Anahita Vossoughi︎Bilateral Symmetry︎Anahita Vossoughi

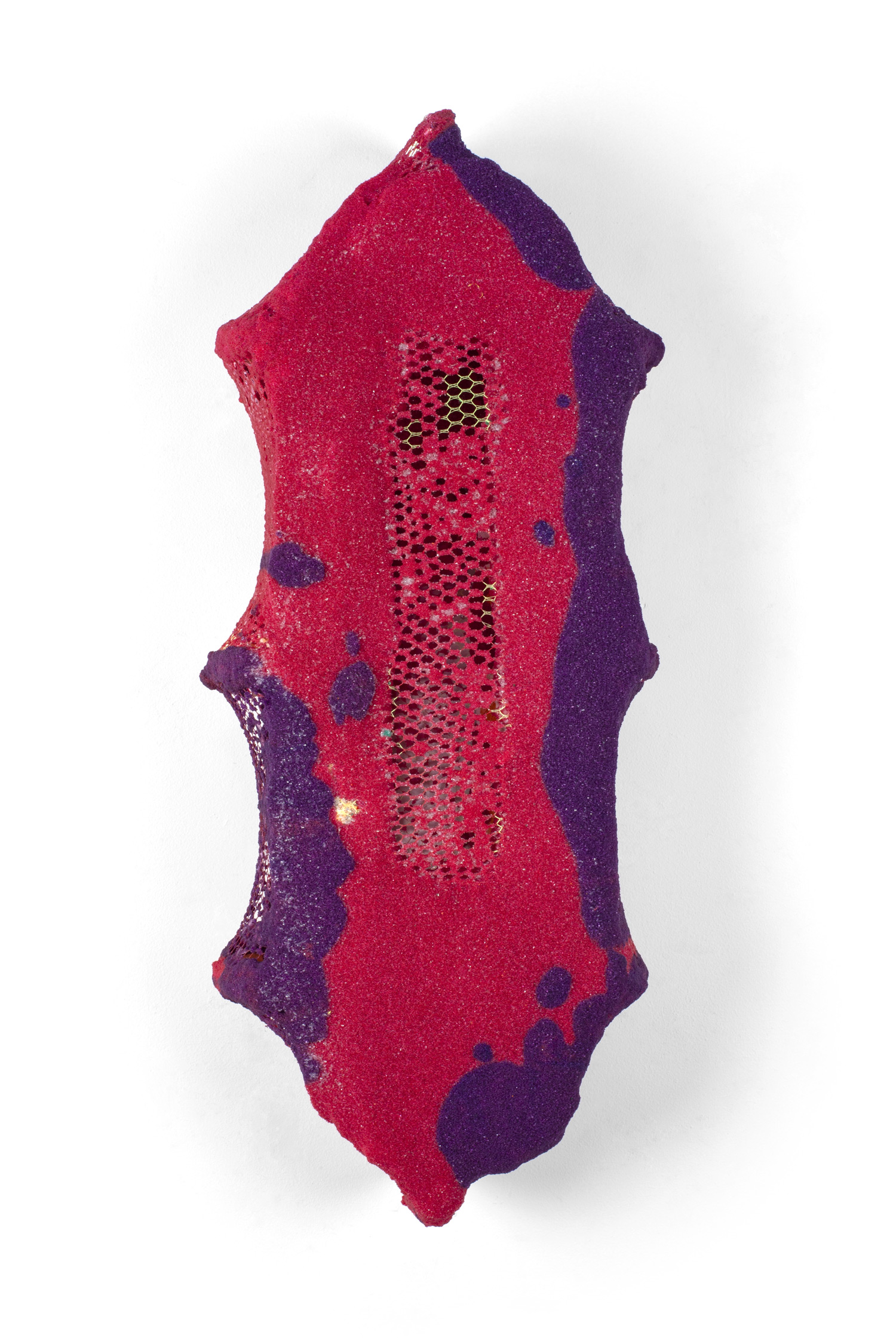

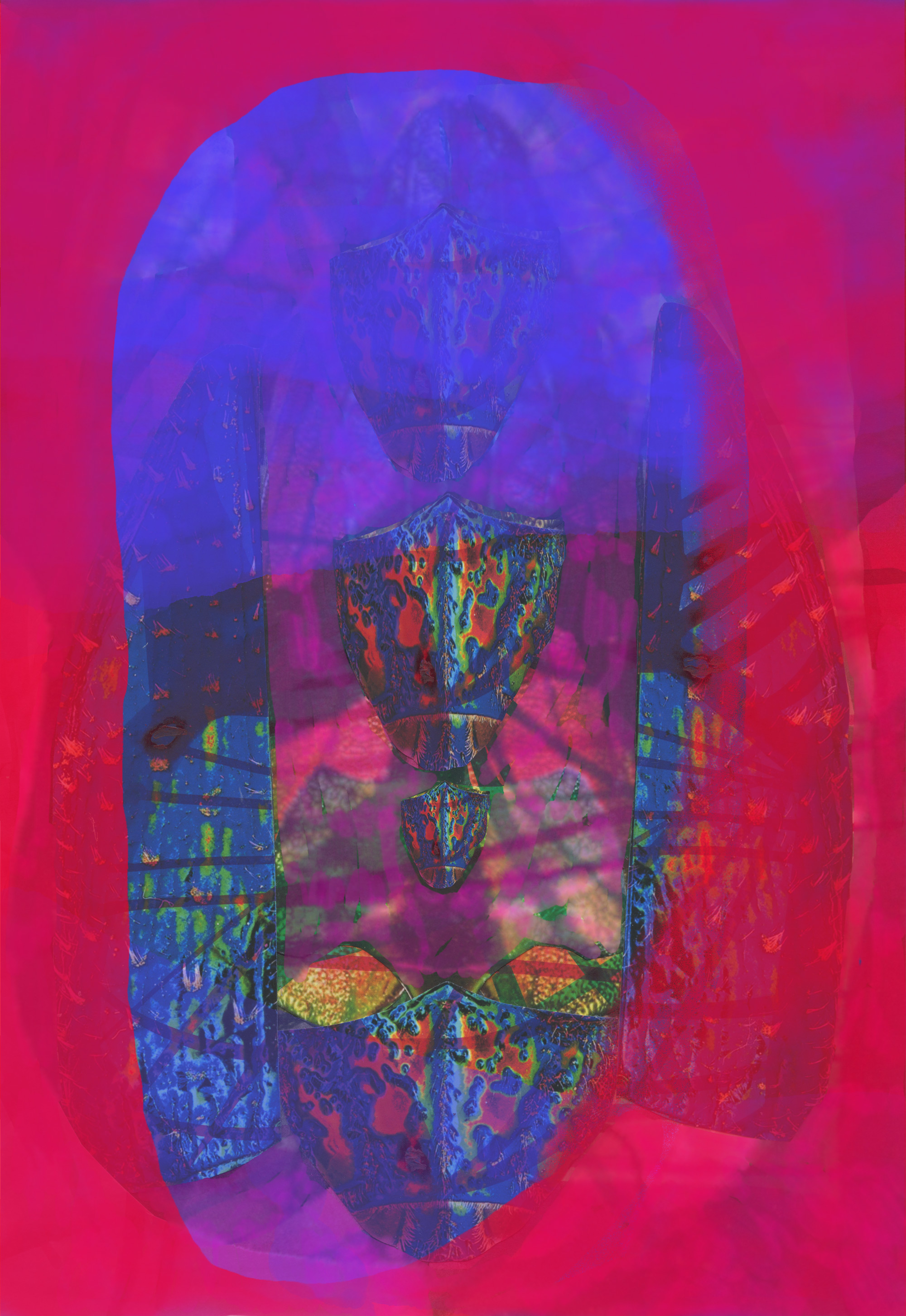

Exoskeleton for Protection: Ice Shield, 2021.

Acrylic and oil paint, ink, clay, sand, polystyrene, sequins, chicken wire, and fishnet on wood, 22” x 10” x 5.5”.

Bilateral Symmetry

Anahita Vossoughi

A few years ago, my then three-year-old son became fascinated with arthropods—any creature that has an exoskeleton. We would read books together with amazing images of arachnids, insects, crustaceans, millipedes, and more. A sea monkey molts seven times in one life cycle; they start with one eye, and end up with three. The female deathstalker scorpion also molts seven times before she can reproduce, and has a lethal sting befitting her name. The fringed jumping spider is a tiny, brilliant killer that often eats much larger spiders by patiently inching closer to her prey, sometimes over the course of days, then pouncing on them and releasing her potent venom. (She will then push her exoskeleton out of the nest after molting.) The lovely jewel beetle has an iridescent exoskeleton that scientists think may help her avoid predators due to her shifting, ever-changing color. Having an inbuilt armor to protect you from a hostile world became a metaphor I was excited to explore. In the context of COVID-19 and political upheaval, this new subject matter felt urgent, constructive, and personal.

For years, I had been making fleshy, intimate, hand- or organ-sized biomorphic forms that grappled with the intersection of feminism, science fiction, and exoticism. I viewed the pupa or chrysalis state as a metaphor for otherness and the vulnerabilities of our corporeality. It was interesting to now explore highly structured forms with bilateral symmetry as enclosures, pedestals, shelves, or homes that these forms could inhabit. My initial impulse was to create exoskeleton-like containers for these fleshy forms, but my process took me elsewhere.

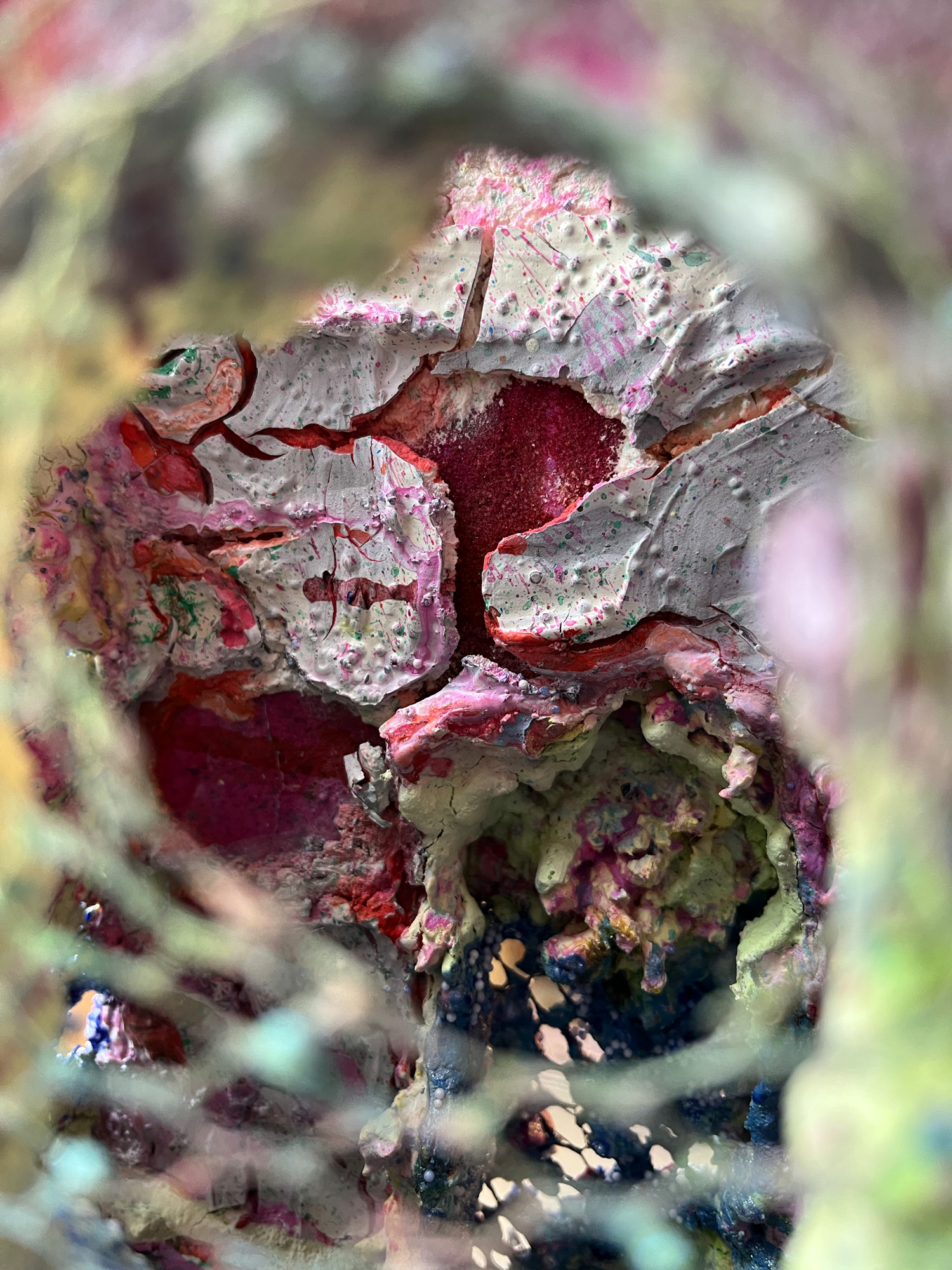

Exoskeleton for Protection: Atom, 2021.

Acrylic paint, ink, hydrocal, clay, polymer clay, sand, and fishnet on wood, 22” x 10” x 5.5”.

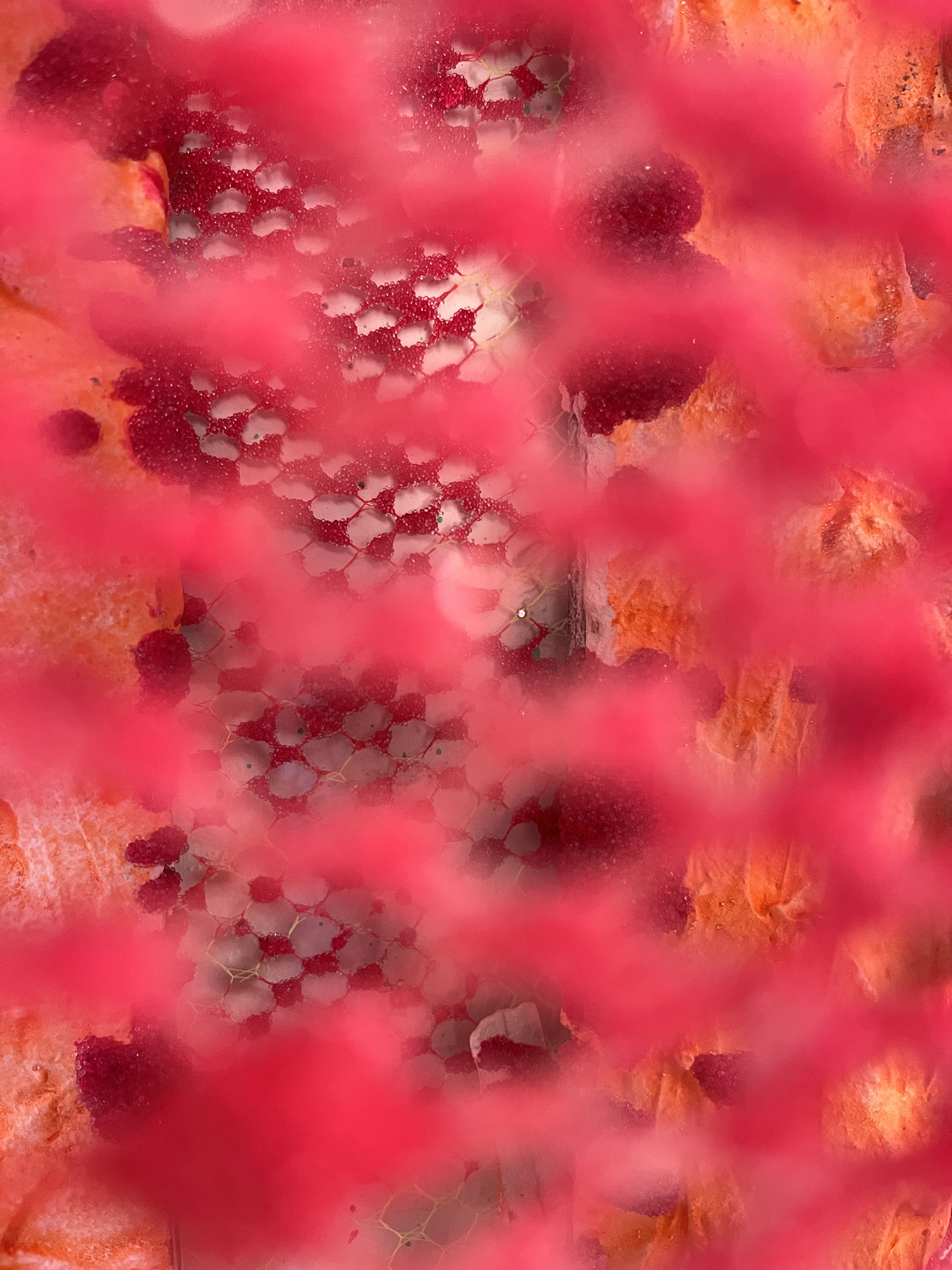

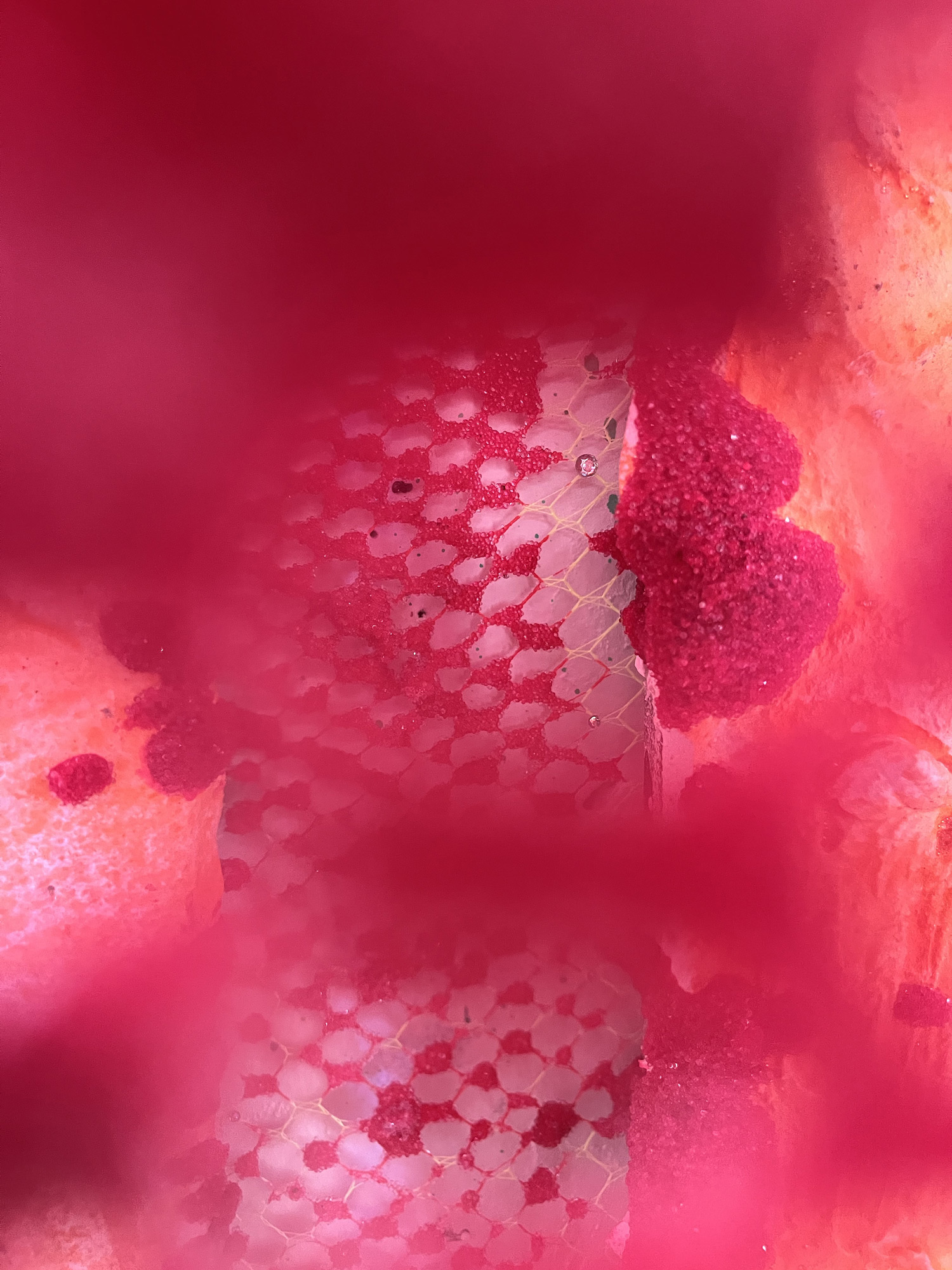

Exoskeleton for Protection: Net Laser, 2021.

Acrylic and oil paint, ink, glass beads, clay, polymer clay, sand, and fishnet on wood, 22” x 10” x 5.5”.

Exoskeleton for Protection: Time Machine, 2021.

Acrylic paint, ink, sodium bicarbonate, calcium carbonate, clay, polymer clay, sand, and fishnet on wood, 22” x 10” x 5.5”.

Exoskeleton for Protection: Polystyrene Ocean, 2021.

Acrylic and oil paint, ink, polystyrene beads, clay, polymer clay, sand, and fishnet on wood, 22” x 10” x 5.5”.

Exoskeleton for Protection: Rib Encasement Study, 2021.

Digital drawing, dimensions variable.

I began by making digital studies and plans for these forms to be cut through laser cutting, a clean and efficient process carried out using a CO2 laser in a digital fabrication laboratory. Sometimes the digital drawings took on their own lives; in other instances, they were simply data for the laser cutter to know what to cut. Through this method, I was able to achieve mechanically-reproduced armatures with precision, ready to contain my biomorphic sculptures. However, once I began experimenting with my crusty, gooey, pigmented, and tactile surfaces in my studio—outside of the sterility of the fabrication labs—I realized that the forms I was creating were complete on their own. These were not complex pedestals. These were new organisms with built-in forms of protection, just like those that my son and I had read about.

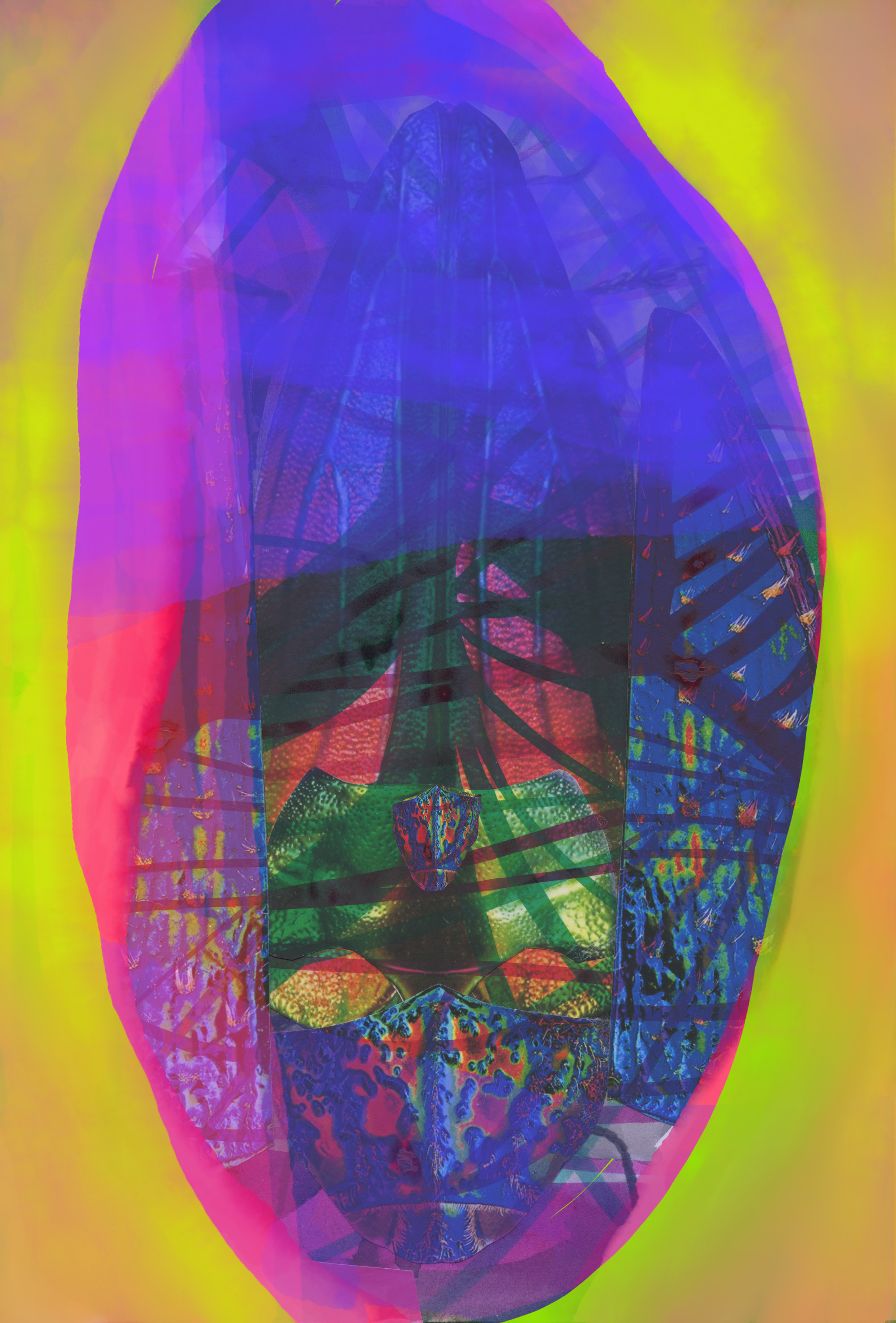

Moth House: Color Study, 2021.

Digital collage, dimensions variable.

Moth House: Study for Laser, 2021.

Digital vector file, dimensions variable.

Moth House: Study for Laser 2, 2021.

Digital vector file, dimensions variable.

Children of Science: Study 1, 2021.

Digital file, dimensions variable.

Children of Science: Study 2, 2021.

Digital file, dimensions variable.

Children of Science: Study 3, 2021.

Digital file, dimensions variable.

Questions I ask myself:

What can a surface communicate? A mossy, lumpy rock, a buckled piece of plastic bathed by the ocean, a pair of iridescent and torn stockings. Clay, sand, dirt, plastic, polystyrene, and nylon. Sequins, glitter, mica, eye shadow, iridescent, pearlescent, glossy, and matte.

How do combinations of materials inform the surfaces of the work?

How can form and surface communicate time and an exposure to the elements?

Can a surface feel ancient and futuristic simultaneously?

How do I make artifice feel like artifact?

How do natural and man-made materials interact with one another?

Can mechanical reproduction be tasty, gooey, painterly?

How can radical juxtapositions of processes speak to issues of hybridity and intersectionality?

I usually take pictures of works in progress while I am at my studio and show them to my son, because he is curious about what I do there. I named this series “Exoskeletons for Protection,” and tell him that the types of powers they give us dictate how they make us feel. He and I decided that there is an orange one that makes us feel safe and warm. There is a purple one that makes us feel hungry and satisfied, and there is a pink one that is a net that protects us from pink bugs. We imagine that outside of the forms, there is falling slime, and a monster worm with sharp teeth. Occasionally, we imagine that we are on the inside of the forms, and sometimes we are on the outside, slaying dragons. All of the them give us spider powers, so that when we are on the outside, we can protect ourselves.