︎What I’m Working On︎Dana Karwas︎What I’m Working On︎Dana Karwas︎What I’m Working On︎Dana Karwas︎What I’m Working On︎Dana Karwas

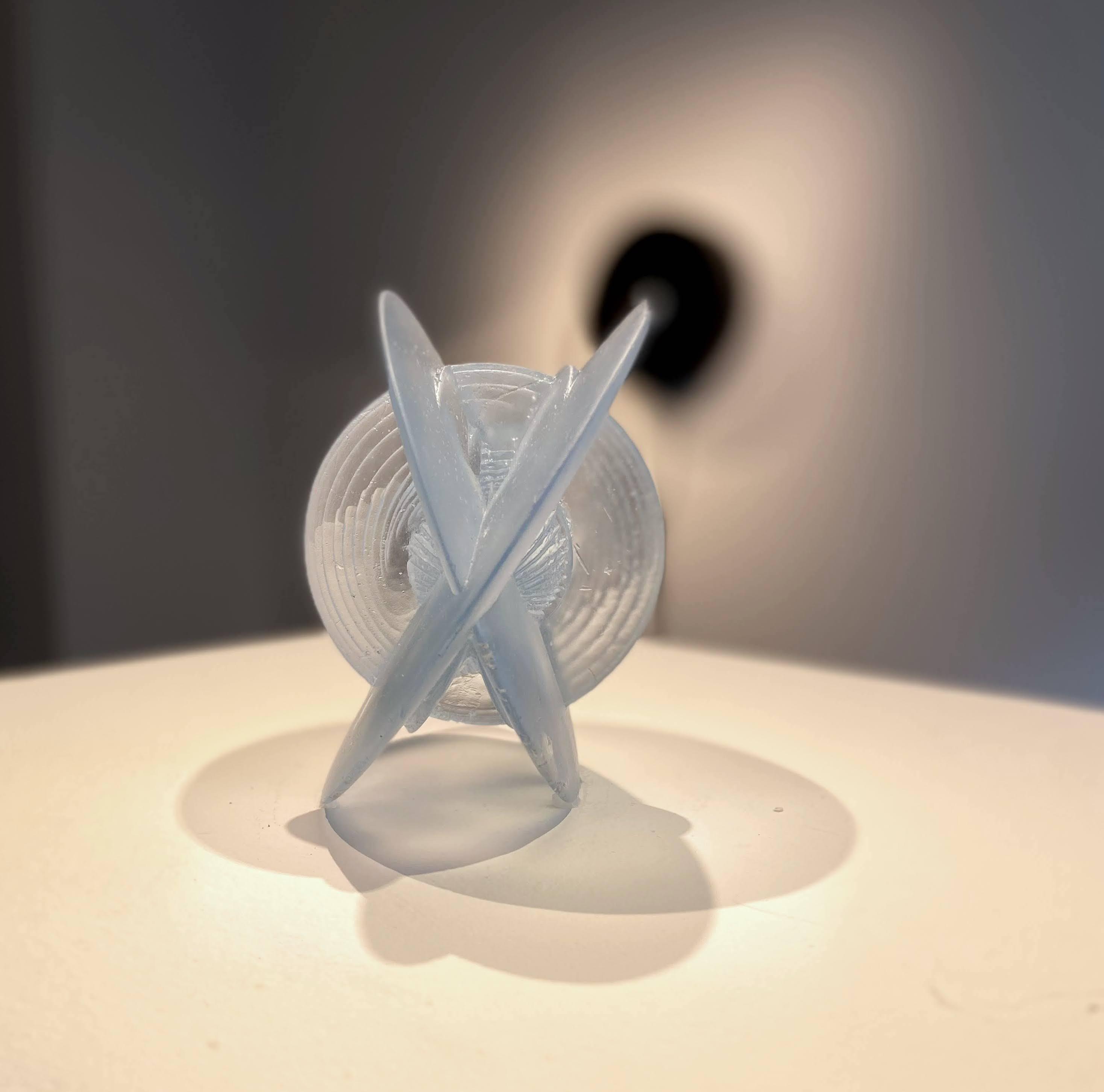

Counter-Curve, Dana Karwas, 2021. Acrylic and volcanic pumice on 60” diameter wooden panel.

What I’m Working On

Dana Karwas

Dana Karwas

In The Princess Steel, a lesser-known piece of circa-1908 speculative fiction by the writer and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, the character Professor Hannibal Johnson describes his attempts to plot out and extrapolate the arc of civilization using 200 years of data made up of “every day facts of life.” Initially foiled by all of the “curves” and “curious counter-curves” of human deeds, he reveals that he has created an invention—the Megascope—that is able to integrate all of these infinitesimal moments into what he calls “the Great Near”: an accumulation of all the normally invisible experiences of each person’s life.

Du Bois himself, of course, was a sociologist steeped in the use of empirical data to visualize larger social phenomena. It was no surprise to learn that this Megascope reveals a fantastical allegory of the colonial structures undergirding modern civilization. The idea is that each individual moment (the so-called “Near” or “Small”) aggregates up into a larger pattern, and that the device allows those patterns to be visible (the previously mentioned “Great Near”). Every moment to an observer now exhibits a kind of shimmering duality—each is a standalone event, but also a potential building block for some larger pattern.

Much of my pedagogy and personal research involves investigating modes of perception. Du Bois’ duality of perception around the “shadows and crossings” of human life is a very intricate idea. I learned about it reading Du Bois’ Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America, which I discovered through CCAM’s Library in Residence; it had been recommended by Holly Rushmeier, John C. Malone Professor of Computer Science at Yale College. My thoughts about it grew into my current show, In a Heartbeat, which draws on the idea of extruding a brief moment of a furtive motion—an innocuous, simple gesture that nevertheless might be a pivotal moment in someone’s life; an adult reaching into a purse to find their keys, or a child stretching for cookies above a stove. Many single moments or simple gestures are slight and mean very little. But without context, our projections while observing them can be maddening, as our minds plot out “curious counter-curves” that can be as fantastical as one of Du Bois’ stories. As a parent, something as mundane as my five-year-old son looking to cross the street feels fraught. Any mundane moment can be imbued with dread; what heart-stopping catastrophe might await? I think often of a split-second—like when someone has just inhaled but not yet exhaled, or the reverse. There’s an immeasurable inflection point here, wherein a whole life can be glimpsed.

I’d been unpacking all this for the past few months, and I began thinking about heartbeats. Every second, there are over 7 billion human heartbeats around the world. Some of these are initial heartbeats. Some are not. Some are ‘normal’, and some are not.

So I began looking at heartbeat data.

Online, I was able to find a trove of datasets showing heartbeat information. Kaggle hosts datasets to help train algorithms—in this case, doctors who are training algorithms to ostensibly identify patterns that might better diagnose imminent heart problems. There were thousands of normal and irregular heartbeat datasets to extract.

Doctors and nurses who have to see something in this data on a daily basis have seemingly occult directions for reading ECG traces. Medical professionals can look at a readout and say, “Ah, this person has that heart condition”... or they might not, and make a lethal misreading. I was struck by the vision required to notice a slight shift in the trace, based on where it falls among a grid of squares on the readout paper. Staring at the repetitive data recalled the radial patterns of a pebble falling into water, or the seasonal rings in a tree. Each of these visual pulses is a movement through time.

Looking at this distilled data—rows upon rows of digits—I felt far away from what I was after. I remembered a cardiologist friend, who used to walk around listening to different heartbeats on a Walkman while in medical school to try to differentiate them by ear rather than by sight. I always thought this was so poetic.

For my initial experiments, I downloaded the heartbeat datasets to try to understand what a heartbeat looks like in numeric form. I started manipulating the data and fed it into different systems: sound frequencies, Bauhaus-style geometry, and even rendered as a lens-like lenticular cloud using a simulation software called Houdini. By re-orienting the data into different systems of representation, I was hoping to have a breakthrough—like Du Bois’ Professor Hannibal Johnson—and see something.

Eventually, my experiments led to this piece, Counter-Curve. Working through a series of compass rotations on a wood panel (which I nicknamed “the flying saucer”), I extruded and re-oriented the data from a single heartbeat into volcanic pumice. To me, the piece feels both incredibly familiar yet completely alien. I’m told that as an object approaches the event horizon of a black hole, time slows down. Some material can get flung violently away from it in the form of hyper-energized jets, much like how pumice is super-heated and flung from a volcano. Even if objects fall into the event horizon, outside observers never even see it reach that point. It slows down until it seems suspended in time. In some ways that’s how I see this piece. It’s a single moment, curving infinitely around on itself.

My typical process involves a lot of iterating on a computer. Playing with forms and generating many different versions of the idea before bringing it outside of the machine and into the physical world through fabrication or other means. This is what I did for my earthquake painting, Tōhoku, which was a way for me to process the trauma of my experience being in Japan on the day of the 2011 earthquake, and which ended with a physical object.

My second piece began with and was partly inspired by sculptor Frederick John Eversley’s 1941 rotational sculpture, Untitled. There’s an essence of rotational motion seemingly embedded directly into his process. I was looking to capture something similar. I wanted to see the heartbeat data as an object—to understand it in dimension, to be able to feel how heavy it is. I took the same heartbeat from Counter-Curve and began modelling ways for it to exist in three-dimensional space. I manipulated the rings and tried to see them in other ways: Turning them, rotating them, finding their axes and centers of gravity.

Eventually, once I decided to bring a model into the real world, I had to choose a medium. I chose glass because I needed a material that could reveal the internal orbital detail while also mimicking the delicate nature of the human heart. At the same time, casting in glass is a very physical process and provided a pressurized inversion of the forces underlying Counter-Curve itself. That lent a nice procedural and physical weight to the eventual object: A piece cast in glass, called Orbital Axis.

Orbital Axis, Dana Karwas, 2021. Glass sculpture, 6” diameter.

Voyager's 1977 Golden Record and the 2,000-year-old Mirror with a Cosmological Design are two objects concerned with how to encode a potentially large amount of information into a single disc. This echoes the “Great Near” concept in “The Princess Steel”. Embedded in any exercise like this is the idea that most information is necessarily left out, and that any perspective on a single moment cannot see the “Great Near”.

︎I wanted to see the

heartbeat data as an object—to understand it in dimension, to be able to feel how heavy it is.

To examine this, I captured motion data from a mundane, everyday gesture and began playing with ways to display it through time. Here again, glass plays a central role—much of our experience of optics involves knowing how light interacts with, is bent by, or slowed down within glass. In First Epistle to the Corinthians, glass is used as a metaphor to explain how truth is not accessible to mortals; that our lived experience as a perspective on reality is merely an image perceived through a dark lens.

But even so, as I mentioned earlier, there’s that shimmering duality around each standalone being inextricably part of the larger pattern, whether perceived darkly or not. In Arc of Near, I’m attempting to negotiate the stillness of a moment frozen in time. The glass has a threshold cut in it, and the rotational motion of the piece appears to allow the viewer to perceive behind the glass. But the viewer must wait for an entire rotation to observe the gesture in full, and can never view it in its entirety at once. Again, it is an innocuous, simple gesture that nevertheless might be pivotal, or it might not. I’m trying to show—through this forced mechanical perception—how we are all primed to interpret something.

Arc of Near, Dana Karwas, 2021. Glass, steel, and acrylic sculpture, 20” × 20” × 5”.

The through-line that connects these new works to previous work is the process, the discovery. Going from data, to two-dimension, to three-dimension. Looking at emotion through technology. Extracting information in alternate ways; using software and weird tools incorrectly; reinterpreting information; and reimagining everything in different systems. Additionally, for this recent show, introducing both motion into the work itself, and a societal angle to the concept.

︎In Arc of Near, I’m attempting to negotiate the stillness of a moment

frozen in time.

Arriving at sculpture indicates a new stage in my practice which I’m really excited about: Placing fabrication and mechanisms between my body and the work feels right.

Using technology outside of what it’s intended—to find new meaning or resolution with an idea—is the essence of CCAM and the work I am doing at Yale. I’m very influenced by everyone around me in New Haven, including the engagement within the courses I teach at the architecture school about mechanical eyes and space architecture. It’s a community thing. Experimenting is highly encouraged, and supported.