︎What I’m Working On︎Madeline Pages︎What I’m Working On︎Madeline Pages︎What I’m Working On︎Madeline Pages

Crater of Vesuvius, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021. Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

What I’m Working On

Madeline Pages

For the past six months, I have been meditating on historical models and images of outer space, such as orreries, astrolabes, and star maps. I want to understand what draws us to examine the solar system and recreate what we see in earthly objects. If you visit the storage facilities of the Peabody Museum on Yale’s West Campus, you can get a glimpse of just how many different kinds of tools and artifacts (some dating as far back as 3,000 BC) exist to look—and because we have looked—up at the sky.

With the support of CCAM director Dana Karwas, I designed an independent study curriculum for the Fall 2021 semester titled “Astronomical Artifacts and Performances” centered on this exploration. The course combined historical research on astronomy and astrophysics from ancient Egypt to the present with investigations of art objects and performances influenced or inspired by the broad theme of outer space. As a theater artist and scholar, this scientific turn was completely new to me, and I set out with the simple goal of broadening my horizons and learning more about a topic that is almost unavoidable these days. Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos, or Elon Musk seem to appear constantly in the news, and I was seeing the influence of the revived attention on NASA and commercial space projects all around me in popular culture and art. For a couple of years now I have been questioning why outer space is so captivating. When faced with something I don’t understand, such as the desire to colonize other planets or commercialize space travel for the benefit of the ultra-rich, I find my way in by reading events through the language of performance. What is exciting and special to me about the medium of performance is its extreme contemporariness, its nowness. The closest we can get to that nowness when studying historical time periods is through communion, so to speak, with physical objects and artifacts, which have an aura, to use Walter Benjamin’s term, of their past use in ritual, in experiment, or in artistic production.

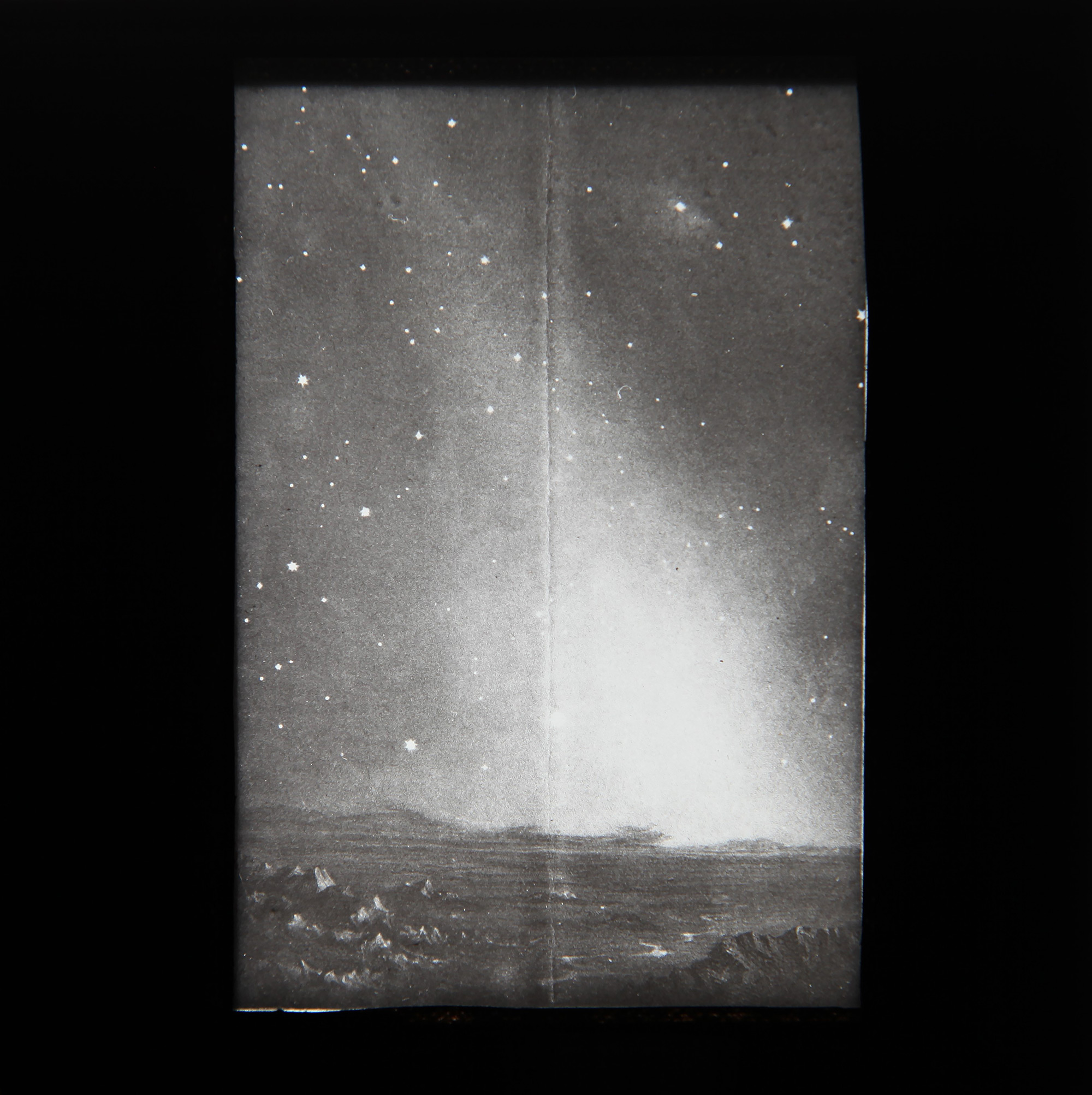

A depiction of the Milky Way visible in the night sky from Earth, reproduced on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021. Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

A depiction of the Milky Way visible in the night sky from Earth, reproduced on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021. Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

Triesnecker, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021. Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

For “Astronomical Artifacts and Performances,” I wanted to go back to ancient astronomical traditions and trace a history of tools and artifacts (many examples of which can be found in Yale’s archives and museums) and ritualized practices of observing the stars through to present dreams of space travel tourism and colonization. In the process, it was important to me to embrace CCAM’s goal of fomenting interdisciplinary collaborations across campus, therefore much of my research was conducted by doing in-person visits to view artifacts housed at Yale, or interviews with other Yale artists and scholars. I am indebted to the conversation, expertise, questions, and suggestions of my many interlocutors that has shaped and transformed this work. During the Fall 2021 semester, I visited the archives of the Yale Art Gallery with Wurtele Study Center Programs and Outreach Manager Roksana Filipowska to look at Chinese bronze mirrors from the third century with mysterious reflective properties. I spoke with Yale Professor of Dance Studies Emily Coates about her dance research at Dartmouth University’s historical observatory. From Professor John Darnell and Alberto Urcia in the Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations Department, I learned about ancient Egyptian calendars, star charts, and cosmological rituals. It was Urcia who suggested that all my theories, discussions, and the objects I was seeing were connected to ideas of perception and shifting perspective. Then I met with Alexi Baker, the Collections Manager for History of Science and Technology Division at the Peabody, to explore the Museum’s storage facilities and look at some of the aforementioned perceptive instruments for viewing and modelling the stars and planets.

What is exciting and special to me about the medium of performance is its extreme contemporariness, its nowness.︎

As a symbolic culmination of my research on human space travel and the study of the universe, I am in the process of building a sculptural piece—my very own space object, and first attempt at creating a work of visual art—that incorporates bits of each of the interactions I have had with these experts. Orbiting Projector Prototype, created in collaboration with projection designer Hannah Tran, is inspired by mobiles and historical models of the solar system like orreries—mechanical moving models of the planets’ positions that were most widely used in the 18th century—and makes use of images from the Peabody’s collection of historical lantern slides. Two small projectors will hang from the ceiling in rotating baskets, projecting images of the Moon and other stellar and planetary phenomena around the space. When the timing is just right, both projectors will shine on opposite sides of a translucent screen mounted on a rotating platform between them, and the will images blend into one or become distorted to create new visions of familiar celestial bodies. In this way, I wanted to visually represent how conceptions of the stars and planets beyond Earth are affected by shifts in perspective and different tools of perception. When it comes the wider universe we’re floating in, our view is narrow and distinct. We cannot see where we are from where we stand, but we can imagine how our planet might appear from afar.

Since ancient times, the mysteries of the universe have been addressed in what we now call science fiction. For ancient astronomers, particularly those in early Egyptian civilization, there was no distinction between astronomy and cosmology, religion and science. Scientifically-advanced observations of the movements of the stars were married to the stories of the gods. When the 17th century German astronomer Johannes Kepler was arguing that the Earth is not static but constantly rotating, he wrote a fictional account of a trip to the Moon in the form of the short novel Somnium (also referred to as The Dream). On this journey, Kepler’s interstellar travelers experience and describe views of Earth from the Moon. By transporting his readers to the surface of the Moon, and allowing them to consider the Earth from a new perspective, Kepler more convincingly demonstrated planetary rotation and how it affects our understanding of the solar system. His story, written and addended over the course of two decades (between 1609-1630) and sent to press mere months before Kepler’s death, is sometimes considered the first work of science fiction.

Aspect of an Eclipse of the Sun by the Earth, as It Would Appear as Seen from the Moon, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021. Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

In my opinion, the most captivating images Tran and I selected for Orbiting Projector Prototype come from the work of 19th century amateur British astronomer, James Nasmyth. What appear to be highly detailed photographs of the surface of the Moon are, I learned, photographs of 3D reconstructions sculpted by Nasmyth in the mid-1800s. These reconstructions were in turn based on observations he made of the Moon from Earth using a telescope he designed himself. The Nasmyth images incorporated into Orbiting Projector Prototype are triply affected by shifts in perspective. They are images of how the lunar surface and sky might appear if someone was on the Moon (and this is nearly a century before humans landed there). To me, these images are as striking as the photographs and video that were sent back from Apollo 11. They evoke the sense of mystery and ethereality that Nasmyth might have felt looking through his telescope. They are, essentially, works of science fiction.

“Astronomical Artifacts and Performances” is the latest iteration of an obsession. Humans’ interaction with outer space, the Moon, stars, and other bodies that lie beyond Earth’s atmosphere, has overwhelmed my imagination. For nearly two years, I have spent a lot of time working and waiting for connections to emerge, like the projections merging in my installation, or planets aligning. What I call perspective play—how we can play with positioning to alter perspective—comes up again and again. I started with a hypothesis about the study of outer space as being a particularly rich site for examining the psychological break—so to speak—between the artistic, creative act of envisioning and the scientific act of theorizing. I have been gravitating towards two quotes that really address what I mean by this. One is from science and science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke’s The Challenge of the Spaceship (1946, later incorporated into the book-length treatise published in 1959), a highly influential and controversial essay delivered shortly after the Second World War, which saw the decimation of Europe, Japan, and North Africa by the new military technologies of rockets and atomic weapons. Clarke’s essay argues for the positive uses of these technologies for the eventual future of human space travel, which he later portrayed in his screenwriting for 2001: A Space Odyssey:

“…the vision must come before the achievement and the truly creative mind must hold the balance between the two.”

The other is from Annie Collins Goodyear’s forward to an exhibition catalogue comprising science fiction-inspired works by mid-century Latin American visual artists, which appeared at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in 2015:

“The shattering of the limitation of earth’s gravitational field by cosmonauts and astronauts signaled not only a technological victory but also a victory of the imagination.”

In both quotes, the imagination, or vision, of what lies beyond Earth’s atmosphere is identified as a first step and an intrinsic element of our understanding and exploration of outer space. I think that most of the today’s popular conceptions of the universe come as much from Stanley Kubrick or George Lucas as they do from Carl Sagan or Neil DeGrasse Tyson. Bezos and Musk, who have themselves been empowered by a love of science fiction space narratives like Star Trek, obviously grasped the importance of having and selling a clear vision of human life in space before either had even a single successful rocket test launch. This is the art of the New Space industry.

Normal Lunar Crater, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021.Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

Normal Lunar Crater, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021.Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

Group of Lunar Mountains. Ideal Lunar Landscape, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021.Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

Group of Lunar Mountains. Ideal Lunar Landscape, James Nasmyth, originally published in 1874 and reproduced here on a lantern slide. Photograph by Alexi Baker, 2021.Courtesy of Baker, Division of History of Science and Technology, Yale Peabody Museum.

Humans’ interaction with outer space, the Moon, stars, and other bodies that lie beyond Earth’s atmosphere, has overwhelmed my imagination.︎

We’re talking more and more about outer space at CCAM these days. From podcast interviews with astronauts and aerospace engineers to students taking Zero-G flights for Karwas’ space architecture course “The Mechanical Eye: Ultra Space,” CCAM is seeking out collaborations with experts in the field. I think it is important that artists, and particularly performance artists who are invested in our social and cultural future also take part in these collaborations. The way things are going, commercial space projects will not long remain niche or a fad of the ultra-rich. This is a multi-billion-dollar industry with government and military support that is vying for power over the future of the planet(s). Artists aren’t heroes, but their voices can influence the form that these conversations take and invite in other non-experts. I’m glad that CCAM is a place that can bring different kinds of thinkers and makers together in this way. I hope with my own work to capture the imagination of CCAM associates and start a conversation.