︎What I’m Working On︎Matthew Suttor︎What I’m Working On︎Matthew Suttor︎What I’m Working On︎Matthew Suttor

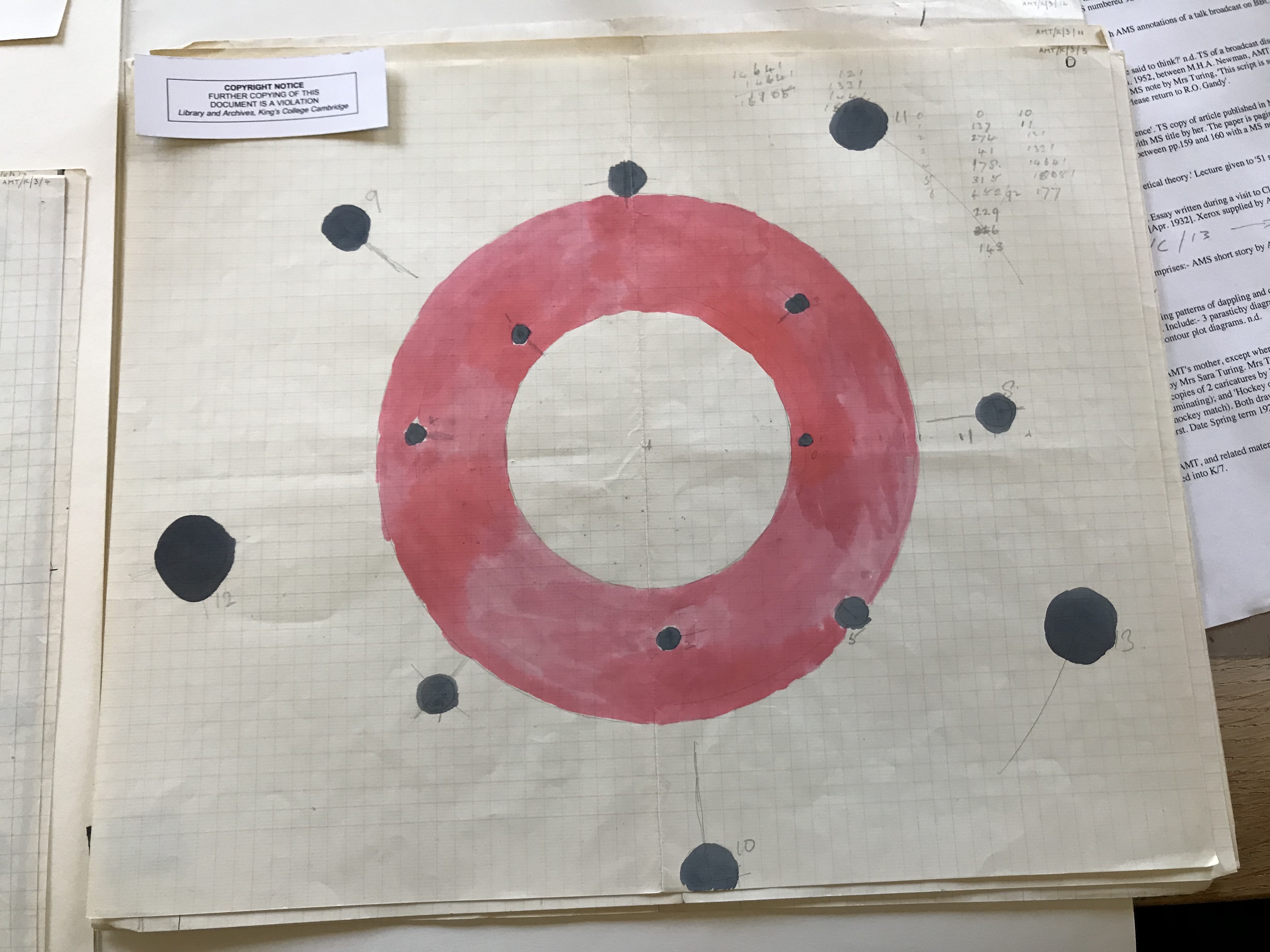

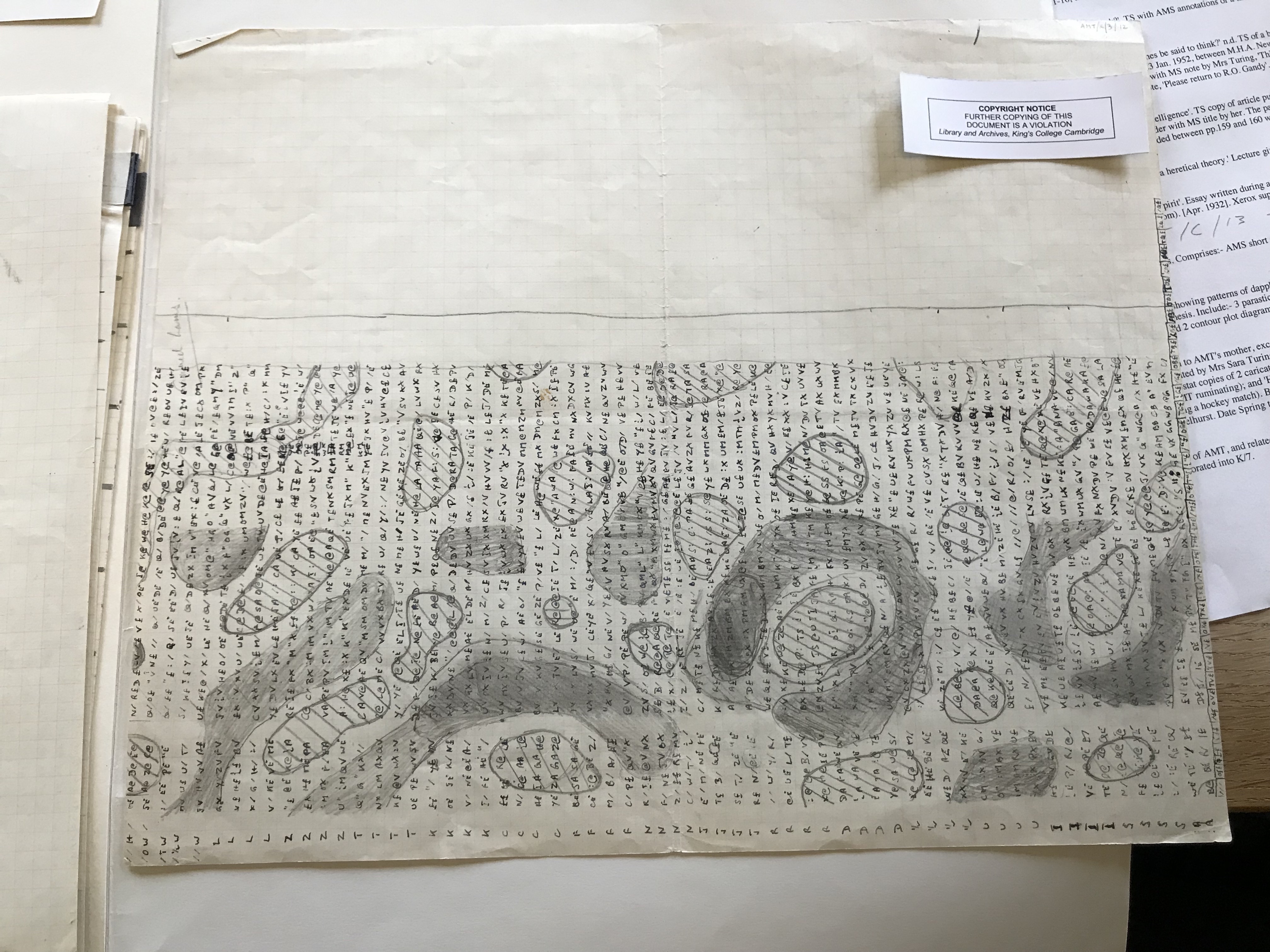

Unpublished writing of A.M. Turing. Copyright: The Provost and

Scholars of King’s College Cambridge, 2019. Photo by Matthew Suttor.

Scholars of King’s College Cambridge, 2019. Photo by Matthew Suttor.

What I’m Working On

Matthew Suttor

…trying to understand what the machines are trying to say…

I am composing an opera about Alan Turing, with the support of the Yale Center for British Art and the Blended Reality program at CCAM. I am collaborating with producer Hugh Farrell (Dramaturgy YSD ’15), programmer Dakota Stipp (Sound Design YSD ’20), and designer Wlad Woyno (Projection Design YSD ’18). The opera will feature Hadleigh Adams, a baritone from New Zealand who now sings with the San Francisco Opera. The opera, to be developed at CCAM in the Leeds Motion Capture Studio, will not be a biographical piece about Turing, but an exploration of his thinking about both the limits and the promise of computation through his writing and interviews. Our opera may be a giant Turing Test.

In the summer, I was in Europe to meet with collaborators to begin work on the new project. After working on the initial design and text concepts with Hugh and Wlad in Lisbon, Hugh and I visited the Turing Archives at King’s College, Cambridge. Our view from the archive reading room looked directly out at King’s College Chapel.

In silent tandem, Hugh and I read through the original typescripts of Turing’s published papers, complete with jaw-dropping marginalia in his handwriting. The opening of Intelligent Machinery, A Heretical Theory, reads: “You cannot make a machine to think for you. This is a commonplace that is usually accepted without question. It will be the purpose of this paper to question it.” Then in the margin of the final paragraph, Turing handwrote, “trying to understand what the machines are trying to say.” It was a stunning revelation to us of Turing’s own struggle to make known the possibility of Artificial Intelligence. In opera, you need to find a reason to sing, and I think we found it.

Unpublished writing of A.M. Turing. Copyright: The Provost and

Scholars of King’s College Cambridge, 2019. Photo by Matthew Suttor.

Scholars of King’s College Cambridge, 2019. Photo by Matthew Suttor.

While in Europe I also gave a series of talks about teaching creativity: two at the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space and another at the Arts in Society Conference, which is in Lisbon this year. The talks center around the work my students have made for Gallery + Drama. Now in its twelfth year, Gallery + Drama is an end-of-year celebration featuring performances and installations created by students from the School of Drama in response to the Yale University Gallery collection. This coming spring, we plan to hold this class at CCAM, beginning a new, exciting chapter in cross-institutional collaboration at Yale.

I am excited to be working on a new piece at CCAM. It was nearly twenty years ago that choreographer, dancer, and playwright Tim Acito and I received a grant from the then-named Digital Media Center for the Arts (DMCA) to compose and produce a multimedia dance work called The Ankle Diver. The work incorporated live performance and projections with processed video and computer music playback controlled both in the theatre and remotely in Cincinnati through Internet2, a computer networking consortium led by members from the research and education communities, industry, and government. Photographs from the performance still line the bathroom walls at CCAM.

And Turing is very much in the news. He was recently voted the most influential person from the 20th century by public vote in a BBC broadcast, and his image has been chosen to appear on the new £50 note by the Bank of England. During his short life, he invented the computer as a mechanical avatar to explore the nature of consciousness. In so doing, he opened Pandora’s box and unleashed a now ubiquitous technology on the world. Children growing into adulthood today have never experienced life without a computer: Turing’s legacy lives on in our cell phones and laptops, maps and watches, cars and classrooms. Screens have changed how we interact with each other and our environment. Our opera needs to account for and reflect this rapid development of our consciousness.

Given that, The New York Times has only just published an obituary for Alan Turing this past June, sixty-five years after his death. In The Times, Alan Cowell wrote: “His genius embraced the first visions of modern computing and produced seminal insights into what became known as ‘artificial intelligence.’” We believe beginning our investigation of his vision at CCAM is timely, indeed.